Review by Graham Johnstone

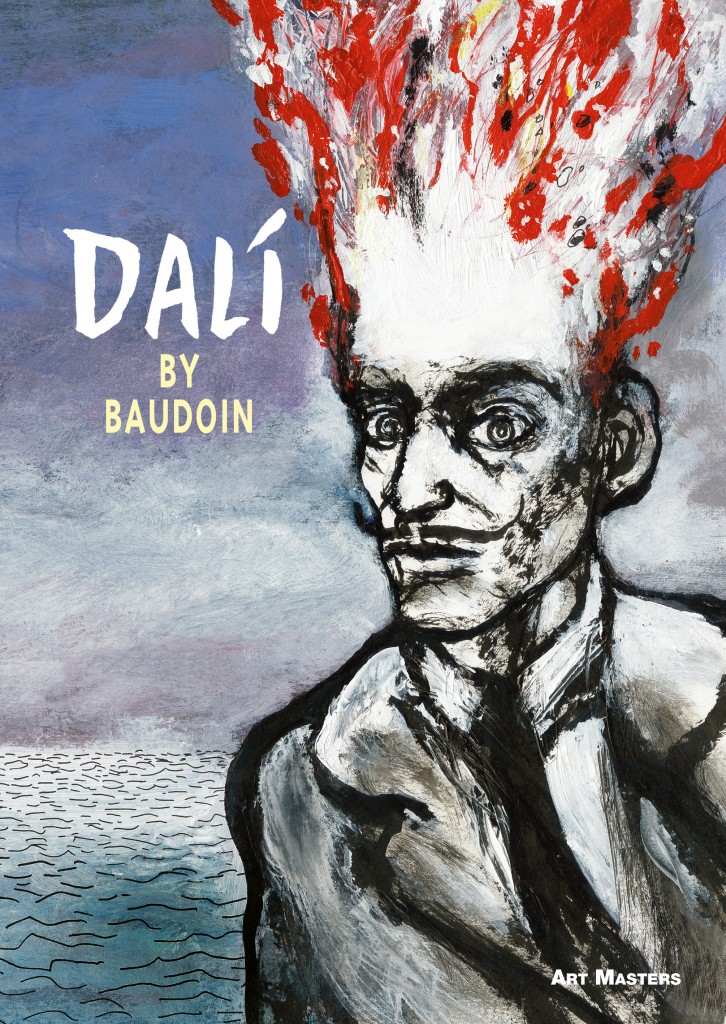

Behind a rather crudely reductive cover, this account of the Catalan Surrealist is both thorough and poetic. Salvador Dalí is simultaneously a larger than life, and mysterious, figure. His name and image are widely recognised, and the general public have an idea of his paintings. His dream images were made palatable, even respectable by his ‘old master’ rendering, creating a cross-over appeal that gave him celebrity, as well as opportunities in other fields like fashion and film. Yet few know much about the person behind the persona, making him another fruitful subject for a biography.

This fifth in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (English translations of artist biographies), is once again, by a creator acclaimed at home, yet little-known in the anglophone world. The French writer/artist known simply as Baudoin, though, seems on a higher plane, with a decades-long career, and dozens of books to his name. Originally commissioned and published by the Centre Georges Pompidou, the prestigious modern art museum, in comics loving France, what they got is presumably what they wanted: one unique artist as seen by another.

Baudoin, in his role as writer, doesn’t shirk on the brief. He takes us through Dalí’s life from sensitive child to budding artist in Catalonia, then his moves through the creative centres of Madrid, Paris, then, as World War II began, to the art world’s new capital in New York. Along the way he meets other key figures: Picasso, Andy Warhol, and Federico García Lorca, with whom he had a long, semi-romantic relationship. Perhaps most crucially, he joins the Surrealists, who shared common interests in, say, the boundaries between dream and reality. They’d later eject him claiming he admired Hitler (though Baudoin gives Dali a sharp critique of him) yet he takes with him the prize of Paul Eluard’s wife Gala. She’d become Dali’s constant companion, his muse, and often model, as well as protector and manager – an early Sharon Osbourne you meet say. All these aspects of Dali’s life then are covered in Baudoin’s book, though some are only mentioned briefly, when they might merit a set piece.

While other volumes in the series have been ‘novelistic’ – aiming to put the reader there with the subject in a well realised narrative present: Dalí is more like a documentary, presented from a distance. Baudoin even introduces an anonymous young couple as narrators and commentators. By the latter pages, this man has become the mature Baudoin reflecting on his own account of Dali. This critical commentary on the events and how they should be depicted, reinforce its identity as more documentary than novel.

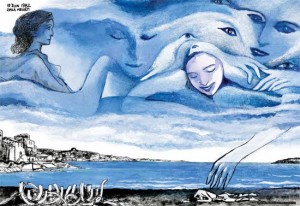

Though Baudoin puts these traces of himself in the text, he’s most on display in the art – he’s less concerned to be true to the material facts, than to the poetic, inventive spirit of his subject. He channels the imagery of Dali’s key paintings, creating new juxtapositions that hold up against the originals. He doesn’t mimic his subject’s ‘old master’ rendering, preferring flowing ink-lines, and sometimes over-painted and distressed surfaces more like rival Surrealist Max Ernst. Mostly in black and white, the art bursts into colour for the scenes with the inspirational Gala (featured image). Even the most purist Dali fan should find enough familiar, to indulge Baudoin’s stylistic departures.

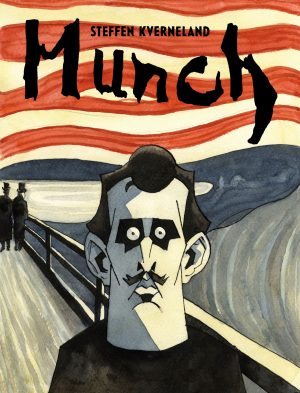

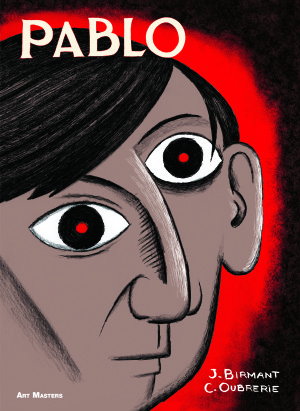

This impressive book gives a full and fascinating account of Dali’s life, conveyed in the spirit, if not the style of his subject. It’s perhaps not such an accessible read as Vincent or Rembrandt, from the same series. However, those interested in Surrealism, painting more generally, or the edges of the comics form should find this a rewarding read.