Review by Karl Verhoven

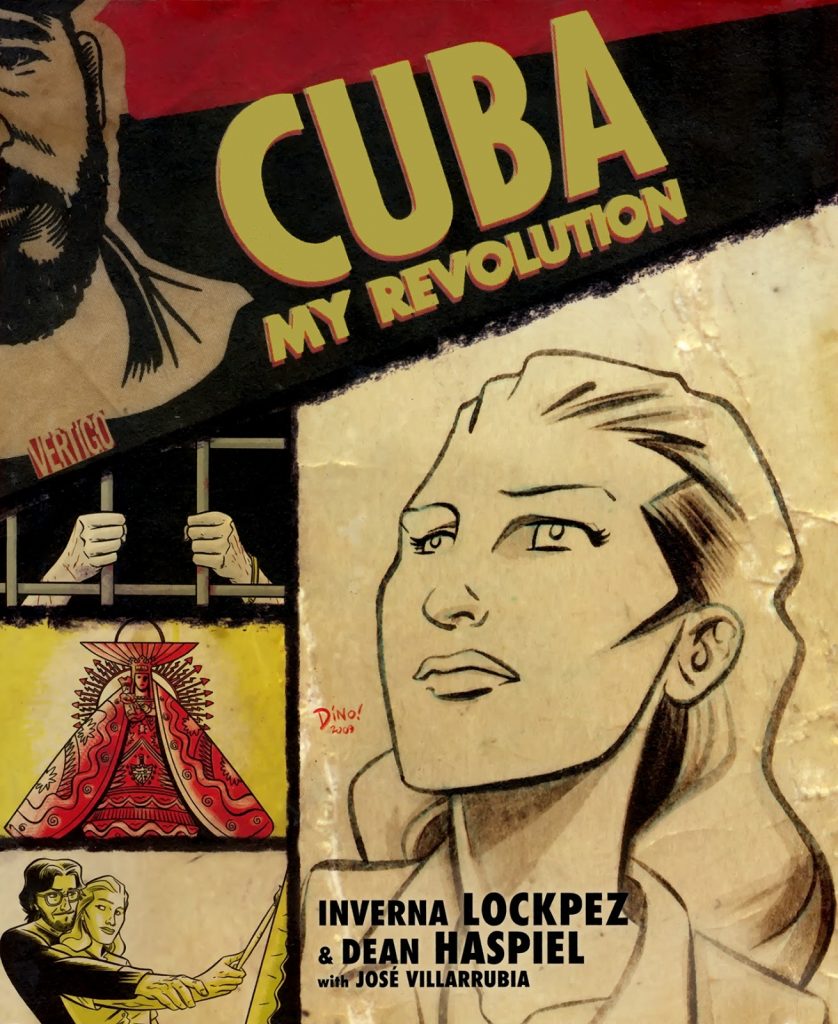

The USA has a very complicated relationship with Cuba, the island just over a hundred miles from the Florida coast. During the 1950s they supported an authoritarian ruler who’d once been a force for good in the country, yet later keen to welcome mobsters who built hotels and casinos, encouraging Americans to gamble there when it was outlawed in many US states. It left the Cuban poor voiceless, so Fidel Castro’s revolution his was an attractive proposition. However, as Castro was openly socialist, the US opposing him was preferable on principle than coming to the aid of the Cuban people. Inverna Lockpez lived through Castro’s revolution before and after, and her fictional avatar Sonya recounts her experiences.

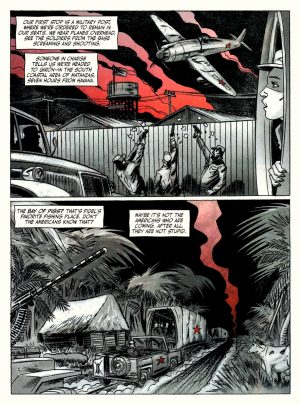

Lockpez opens the book with two quotes, the latter dated 1965 reads “I don’t know right from wrong anymore. Whatever happened to the principles we believed in five years ago? I’m always afraid, all the time. All the time.” It’s a marker as to how much either Sonya or Castro’s attitudes changed in the six years after he came to power. Although a fervent teenage supporter, an early indication of change is the nationalisation of Sonya’s father’s company and a limit on personal savings. In 1961, however enough fervour remains that as a trainee doctor she volunteers for battlefront Red Cross duty on hearing that the US are staging an invasion. It’s the Bay of Pigs.

Sonya suffers several betrayals, some personal, some ideological, before an extremely traumatic experience, yet even that doesn’t shake her faith. This is contrasted with an often trivialised mother, missing home comforts and concocting a succession of crackpot escapes from Cuba, each opposed by Sonya. Interestingly, despite the evidence in front of her eyes, it’s her love of art that finally opens them, and her experiences relating to it that shape her future.

Cuba My Revolution is a story almost able to tell itself, but despite being a fine artist of note Lockpez collaborates with Dean Haspiel, whose art starts as very matter of fact, good in relating what happens, only applying artistic flourish to dream sequences. As the story continues, however, the circumstances allow for greater imagination, and his adaptability is key in defining the experience. Shying away from the consequences of violence, no matter how gruesome they may be, isn’t on the agenda, and combining black and white art with red highlights is a potent method of drawing the eye toward a particular image on the page. It can double as an attention grabbing dress or draining blood, so delighting or shocking.

The USA has such a contradictory relationship with Cuba that any statement is mined for political bias, and the ending is perhaps overstated, but that’s an easy comment for someone who hasn’t endured seven years of repression and had their beliefs shredded. Lockpez relates erosion of faith, disappointment and betrayal, leaving a Cuba where anyone with a dissenting opinion is no better off than ten years previously under a right wing dictatorship, and it’s not only a personal experience. Late on Sonya chats with someone who ought to have been a prime beneficiary of regime change, yet they too are disillusioned. Sonya’s personal story is harrowing, and any humane person ought to be horrified at what she endures irrespective of political opinion. It’s a story of bravery and strong character winning out over conditioning, and honest personal experience is worth any amount of political dogma.