Review by Karl Verhoven

Reducing Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment to the level of a children’s book is an eccentric idea even for Osamu Tezuka, who began working on it in the late 1940s. He had already adapted Faust, yet adaptations were a relatively new idea for Japanese comics at the time, although the American Classics Illustrated series was instituted in 1941.

Tezuka has the advantage over his US counterparts by virtue of not being restricted by a page count, but while he doesn’t entirely ignore it, by necessity much of the moral complexity and tormented guilt has been cut. The plot concerns a poor student in St Petersburg named Raskolnikov murdering a pawnbroker to steal her goods in the belief that it will lift him from his condition in life. When an innocent person is arrested, Raskolnikov publishes an essay arguing that there are people whose intellectual capacity stands them above concepts such as right and wrong. It brings him to the attention of a judge who starts a relentless pursuit.

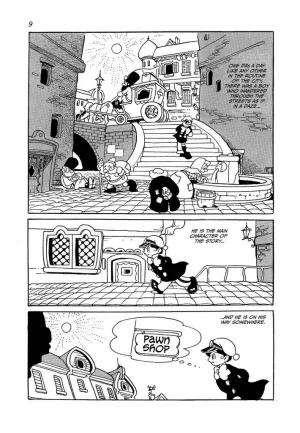

Even shoving the ethical considerations to one side, it’s hardly fodder for children, yet despite Platinum Manga applying an 18+ label, that’s the approach Tezuka takes, in effect producing the Disney animated version. This is complete with comedy mice and a moth and flame scene that can be imagined as a musical sequence. Updating the references and adding slapstick gags and puns to Dostoevsky is almost satirical comment on the miserable nature of his works, and it’s a poor fit. The adult grading is puzzling, perhaps a form of inducement on the publisher’s part, as the comedy visuals don’t merit it. It’s possibly down to references of a supporting character’s trade in prostitution. “Your daughter is still a whore”, shouts a man from the pub door. “No, you’re wrong! She’s a prostitute and supports our whole family”, replies an impoverished official.

Ignoring Crime and Punishment as an adaptation, which is difficult, and taking Tezuka’s work on its own merits, still doesn’t result in great satisfaction. The best aspect is the graphic sophistication. Several early pages feature pairs of similar vertical panels extrapolating events on a staircase, a confident Raskolnikov looms as a giant over those he verbally bests, and Tezuka employs eye-catching silhouettes. The farcical exaggerations are well composed, energetic and comical, with the final chaotic scenes something the UK’s Leo Baxendale would begin producing a few years later. Unlike Dostoyevsky, it seems Tezuka has some sympathy for Raskolnikov, or at least intends that his readers do, drawing him as an innocent Pinocchio type, his self-confidence and arrogance almost entirely absent, never mind being haunted by his crime. Other cast members are more appropriate, with Luzhin convincingly portrayed as a sleazy rich guy.

After the moth and flame sequence Tezuka finally gets to grip with some of the torment Dostoevsky inflicts on Raskolnikov, and his second meeting with the judge has some weight, but following that it’s soon back to knockabout comedy illustration.

Crime and Punishment stands head and shoulders above any comic being produced in the USA in 1949, but hasn’t dated well. It’s for Tezuka completists only.