Review by Frank Plowright

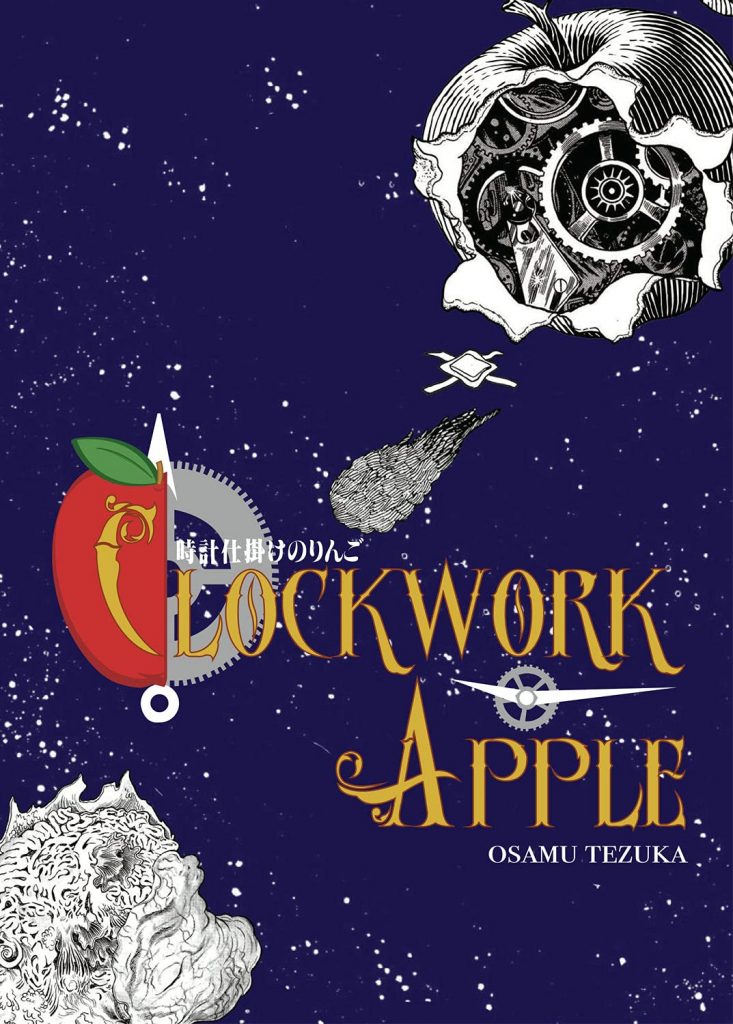

It’s pleasing that the 21st century’s second decade is finally seeing the English release of short stories Osamu Tezuka produced from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, expanding his creative output and broadening his audience. This material was produced over roughly the same period as the content of another short story collection Under the Air, stretching a little further, from 1968 to 1973, but while some of those stories dealt with unpleasant subjects, these plummet way further down the scale.

Drug experiments with population control, rape as blackmail, a Nazi concentration camp commander, a military organisation looking to take over the nation, a boastful robber trumped by a murderer… By the time they’ve all been read, the final tale of human inhumanity and death via sex is just par for the course. These are dark and disturbing exorcisms disguised by exaggerated cartooning. Were the stories not produced over a five year period when Tezuka was also creating other, cheerful, work there’d be worries about his mental wellbeing.

The title piece echoes the title of a more famous work, something Tezuka freely admits, but it bears no further comparison to A Clockwork Orange, in this instance a psychological thriller about the sole person who realises something’s wrong in his community. It’s sequenced third, and follows two stories that have nasty moments, and are also strangely unsatisfying for Tezuka, the broad ideas novel, but the execution ordinary. Well, for Tezuka at least. The cartooning is faultless.

While Tezuka explores his dark side, he’s also experimenting with form, so different styles grace these stories. The most experimental artistically is the tale of a man thinking he’s discovered the love of his life, the attraction founded on a mutual admiration of broad contemporary artistic culture. Music, art and weather are incorporated imaginatively, although muddy grey tones indicate several pages originally in colour. Tezuka’s reflection of mood is notable throughout. A noir taxi ride occurs at night and is drenched in shadow, while two tales set in space have a retro-futuristic gloss, with the clumsy anachronistic touch of an astronaut using a reel to reel tape recorder somehow endearing.

However, for all the artistic skill, these aren’t Tezuka’s finest stories. It’s as if the bleakness of intent has dulled his commercial sensibilities. The best of them are two straight crime dramas, the taxi ride, and a tale about an assassination both dripping with tension. In others some twists work while the endings to the remainder are either more predictable or not especially imaginative, so on the evidence of this selection horror isn’t Tezuka’s greatest strength.