Review by Frank Plowright

The Chernobyl nuclear power station is located in Ukraine, and since Russia’s 2022 invasion it’s once again prompting global concern. In 1986 Ukraine numbered among the countries annexed as part of the Russian controlled Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and was the site of the world’s worst ever unplanned nuclear incident.

Matyáš Namai’s account opens with a table noting radiation absorbed in mSv units. You’ll absorb 0.001 from eating a banana, .002 from a chest X-Ray, and .02 from an eight hour flight. 1 mSv is the maximum recommended public exposure limit. 100 mSv increases the risk of cancer, yet a stay on the international space station exposes astronauts to that amount and somewhere up to half as much again, and the average dose absorbed by those involved cleaning up after the Chernobyl disaster was 170 mSv.

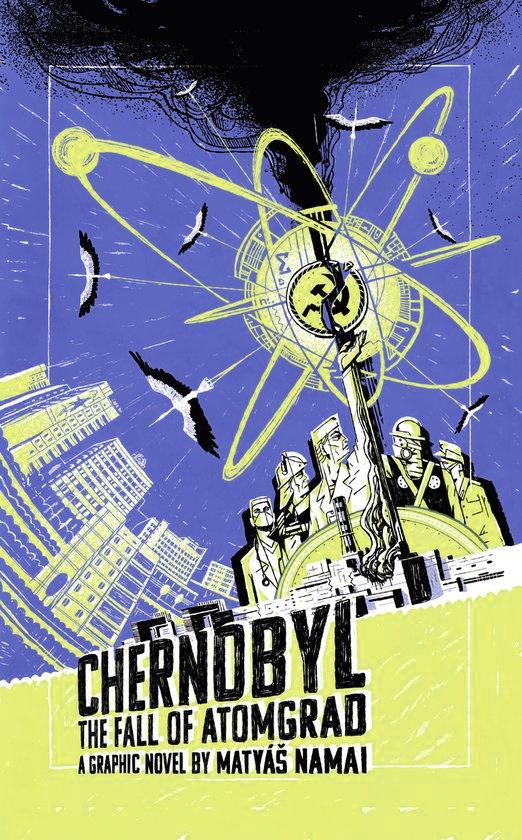

Chernobyl was built in 1972 along with Atomgrad Pripyat, a new city to house workers. Namai relates how political concerns were prioritised, resulting in the construction period being considerably reduced through use of unsuitable materials and jerry-rigging. Administrators took the praise and rewards for rapid completion, while anyone raising safety concerns was sacked and blacklisted. Through arrogance, hubris and corruption it became the literal accident waiting to happen.

Namas walks readers through process, explaining the science through easily understood comparisons and diligently explains small details, such as firefighters being hindered by the melting roof tarmac sticking to their shoes. He personalises the tragedy via representational workers and scared administrators prioritising political outcomes over public safety, and notes the immediate response being the imposition of state secrecy. The astonishing levels of secrecy within the Soviet Union still astound, an example being an entire city built by gulag prisoners not featuring on an public map, or a 1957 nuclear disaster that remained unknown to the wider world until the 1970s.

The detail provided is necessarily gruesome, although Namas’ illustration is restrained. He leans heavily on iconography and illustrative skills, as reportage is a genre actively hindered by panel to panel continuity. Additionally, the weakest aspect of the art is people, who’re often sketchy and inconsistently proportioned. The colours are restricted to blue and bright yellow, occasionally combined to form the green of a military uniform. It’s offputting to begin with, but it comes to represent frankly unearthly circumstances.

While the circumstances of the disaster are explained, far more space is occupied by the effects, particularly on first responders and powerful sequences feature ordinary people living in the area. The accuracy is given weight by quotes and reference to contemporary experts, although a surprising omission for a reference work is the lack of any background material. There’s no bibliography, and no indication from where what seem to be direct quotes are sourced. The presumption is that those from court proceedings are directly from transcripts.

Appalling moments continue throughout as Chernobyl explains a tragedy compounded by lies and cover-up, a technique now so frequently adopted in the UK, but here with a far greater human cost. The official death toll including only people who died during the actual explosion is a depressing example, ignoring the thousands who subsequently died from absorbing radiation. This is a diligent, but depressing chronicle from which many lessons should have been learned. Have they?