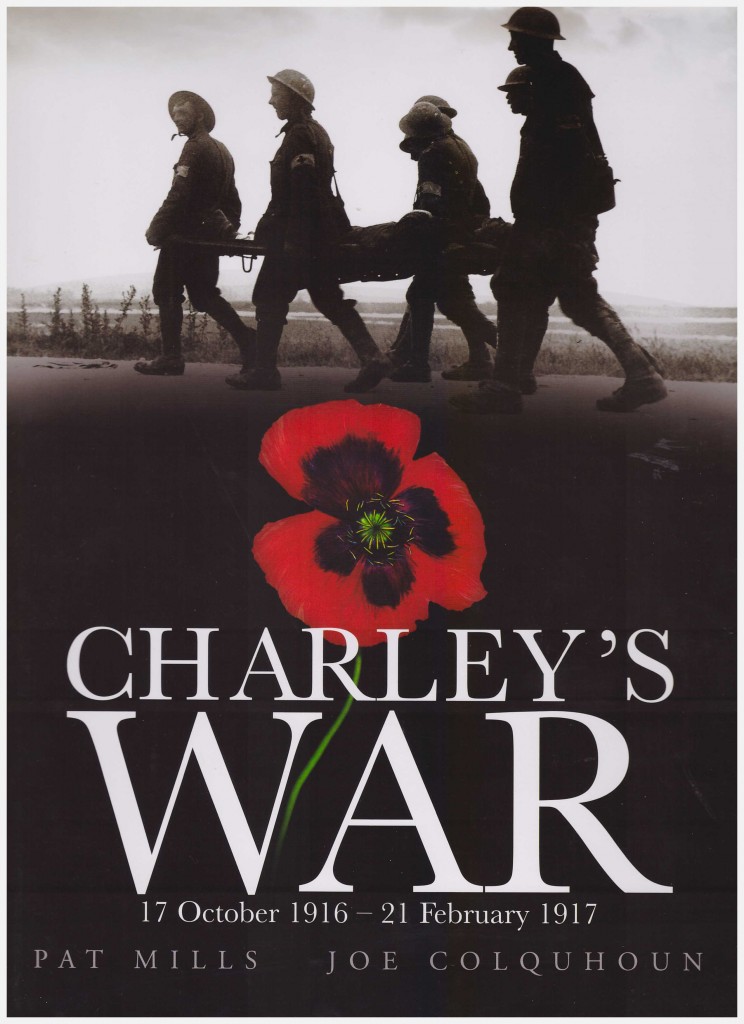

Review by Frank Plowright

In his afterword to the previous volume Pat Mills noted that his writing for Charley’s War until this point had been subconsciously handicapped by ingrained training in the expectations of British war comics. Considering what he’d already achieved, others may feel he’s being too harsh on himself. Yes there had been the occasional piece of gung-ho action, but that was surely the case on the actual battlefields, and it’s not as if Mills had prioritised such sequences. Here, he claims, the commitment to total reality kicked in.

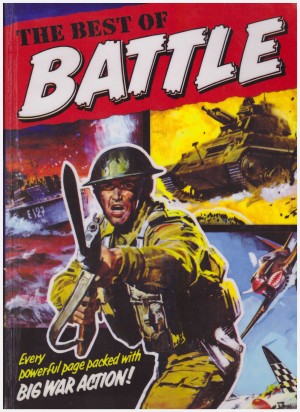

It’s certainly apparent with the battle that occupies half the book. To this point Charley Bourne had spent time in the trenches, and Mills had accentuated the ghastly conditions, but there hadn’t been a sustained spotlight on trench warfare. Colonel Zeiss and his Judgement Troopers launch a blitzkreig on the British occupied trenches, and chapter after chapter portrays the desperate defence put up by the Tommies. There is an ironic ending to the sequence with Mills portraying the German commanders as also out of touch and ruled by the aristocracy, perhaps a deliberate contrast to the portrayal of Germans in the World War II material alongside the strip every week in Battle when originally printed.

Much of the second half of the book turns the spotlight away from the battlefields to the hospitals and the homefront, with Charley suffering the consequences of the blitzkreig. As is stressed, though, he’s one of the fortunate. He survived.

While Mills’ in-depth research and artist Joe Colquhoun’s unstinting dedication to graphic realism ensures this is a strip with high worthiness quotient, neither ever forgot they were telling a story first and foremost. It’s interesting, then, that most of the primary villains seen were British, calculating and callous individuals caring nothing for the lives of those they considered beneath them. With Charley back in London, another is introduced in this sequence, odious munitions factory owner Sir James. He’s caricatured dropping in on his premises in top hat, cape and spats, and refuses to evacuate the workers even with the threat of bombing imminent. It leaves a cliffhanger leading into the following volume, which advisedly drops the dates as titles, being called Blue’s Story.

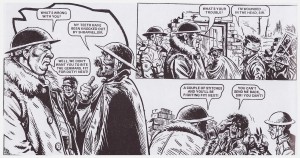

Colquhoun’s art is again magnificent, dense, realistic, starkly contrasted black and white with an incredible sense of humanity. Whether scripted by Mills or thrown in by Colquhoun, the humanity’s indicated via a deliberate homage to All Quiet on the Western Front (presumably the Lewis Milestone film rather than the John Boy Walton version).

The stories reprinted here are approximately three years into Charley’s War, during which time the strip had gradually floated to the top of Battle’s popularity polls. This led to what was considered a prestige position with the strip starting in colour on the front cover. Unfortunately this is to the detriment of the strip with a portion of the story taken up with a large splash image, and in more recent times the colour not reproducing well in black and white.

It’s also obvious in this volume that Titan didn’t have access to decent copies of the artwork, and much of it appears to have been reproduced from the original muddy printings. It’s to be assumed that tidying up the art wasn’t financially viable.

Extras here include an interview with Colquhoun carried out in the 1980s in which he reveals his admiration of Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby art, Steve White’s article on the zeppelin bombing raids, and Mills’ annotations to the reproduced strips.