Review by Frank Plowright

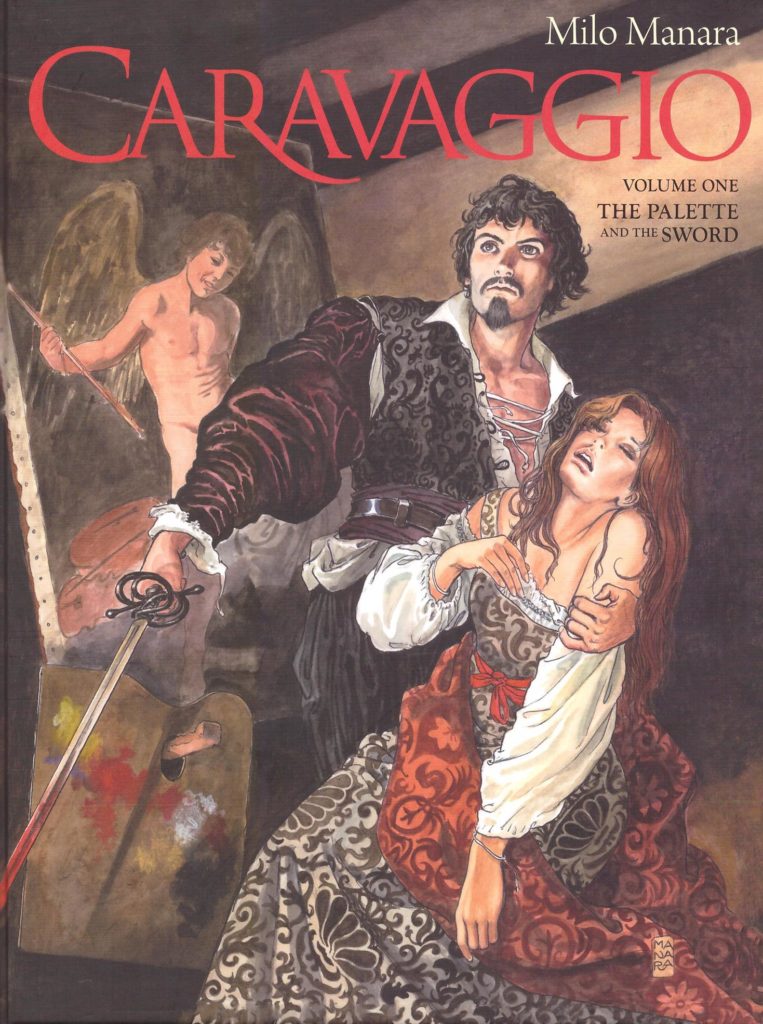

Caravaggio is a fascinating biographical subject. He’s an astounding painter whose works are acclaimed masterpieces hanging in the most prestigious national galleries almost four hundred years after his death, yet also a man constrained by the church led morality of his era, and quick in resorting to violence. He’s a man of contradictions, and much the same could be said about Milo Manara. An immense artistic talent is visible on almost every page he’s published, the delicacy of his line and the poise of his panel compositions an unbeatable combination, yet what he’s chosen to write to accompany that wonder rarely comes close to matching that skill. Some collaborators have stretched him, like Hugo Pratt and Alejandro Jodorowsky playing to Manara’s strengths, and others don’t seem to have considered the artist he is when pitching their story. It’s led to a vastly uneven body of work. So where does Caravaggio stand among it?

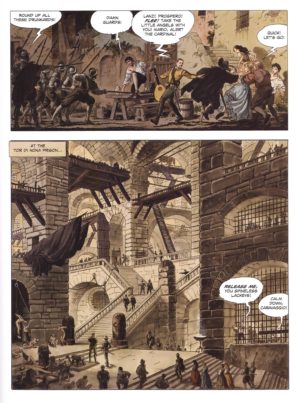

The relief is that it’s the upper end of Manara’s quality rankings. He obviously has an immense respect for Caravaggio’s paintings, and realises that illustrating the life of one of the world’s greatest ever painters means one of the world’s greatest ever comic artists pulling out all the stops. On a superficial level, very few comic artists would be able to duplicate Caravaggio’s works, which don’t look to have been shopped in as there are minor differences in shading and light. Manara’s women are beautiful, his men are beautiful, Caravaggio himself a dashing 1930s movie star, and his locations are beautiful. An art historian might know if Manara has adapted 16th and 17th century paintings for his scenes of Rome, but so many panels evocatively recreate what we imagine the times to be from the paintings that survive. The sample page’s top panel echoes the drama of Caravaggio’s paintings, while the impressive scale of the prison below would appear to be more the product of imagination.

Manara’s interpretation of Caravaggio’s personality is partially fictional, a graphic novel equivalent of a TV drama claiming to be based on real events. Manara fills in gaps between scraps of known moments, and is also generous, contradicting most accounts. His Caravaggio is bawdy and with a temper, but always in service of virtue. The reality appears to have been that Caravaggio just enjoyed a good brawl, and had done since his mysterious departure from Milan. This is not addressed by Manara who picks up Caravaggio arriving in Rome, and finishes this first volume with his departure. In between he earns commissions from the church, so important to painters of era, and earns the enmity of a Roman nobleman. Due to lack of information, Manara has to construct him, supplying a taunting bully not far removed from a gangster on whom the Punisher would set his sights in an establishing sequence. This is accompanied by a contradictory leading woman around whom Manara constructs a nice story about the church rejecting Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin painting. Given the lack of available reference, fictional veneer is a necessity if a story is to accompany established fact, but for all his respect, Manara plays fast and loose with what is known, having Caravaggio leave Rome with the facial disfigurement he actually acquired later.

One-dimensional characters and conflicts service the sight of Caravaggio at work, which is what most interests Manara, and there’s a life to this. Scenes are sometimes posed to emulate paintings, and we see Caravaggio doing the same, and he provides small insights into technique and concept, but without overwhelming. The writing services, and the art stuns.