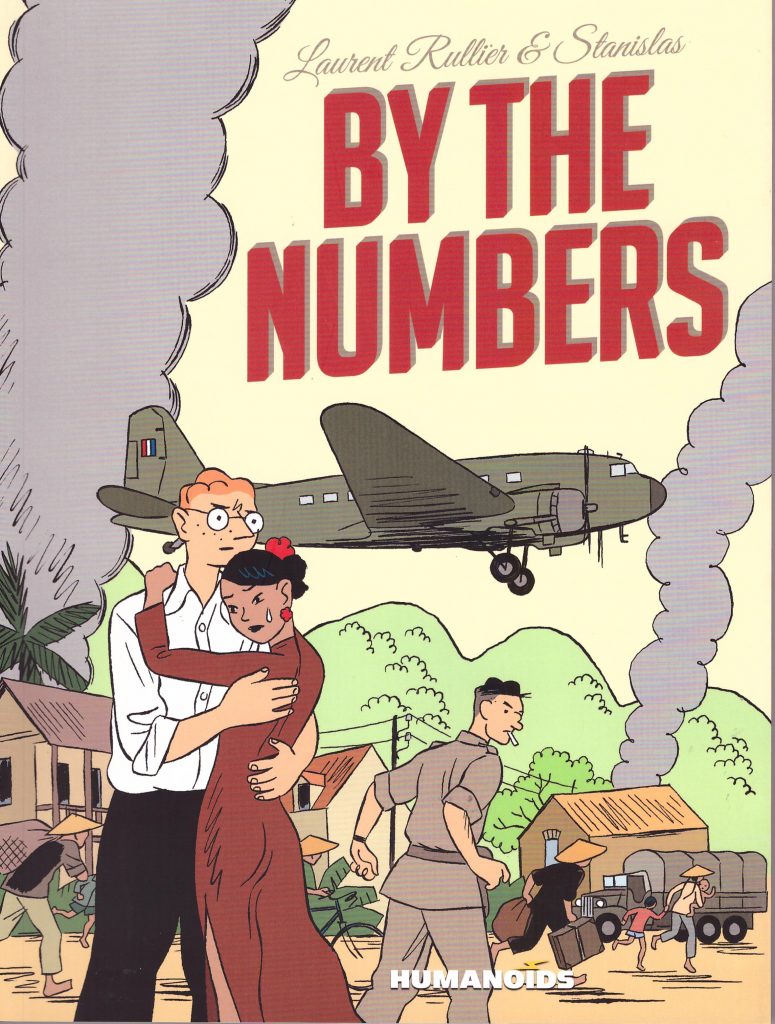

Review by Frank Plowright

In 1968 Victor Levallois appears to be a journalist, and is about to leave Vietnam. His mind drifts back to his first visit, in 1948, when the country was still Indochina. This opens the first of four translated French albums combined here, spanning seven years of Levallois’ life and over them Laurent Rullier presents Levallois changed by his experiences, becoming the man we see in 1968. Twenty years previously he’s a timid young accountant working for a French import/export firm.

Stanislas Barthélémy’s claire ligne cartooning (no shadows) is an obvious tip of the hat that much of By the Numbers is a homage to Tintin. It covers more adult topics, but features the same sort of dogged adventurer with a propensity for stumbling into situations, and a full set of contrastingly seedy and exotic locations. Other visual clues point the way, such as the distinctive red and white checked pattern on a vehicle, and the little wavy lines indicating movement. Over all four books Barthélémy is magnificent, even if it’s persistently strange seeing the style used for more graphic murders, scenes of drug addiction and in brothels.

Two connected opening stories are set in the fading colonialism of Indochina, where Levallois arrives as a naive young man fortunate to fall in with a varied bunch of people sharing a massive old house, each of them able to teach him something about Saigon and about life in general. He stays for three years, finding himself in dangerous situations he’d never have dreamed of in provincial France, and undergoes a postponed coming of age. By late 1950 Levallois is back in France, shaken by his experiences, and belatedly remembers he has a letter to deliver. The circumstances arising from that begin his next adventure. A final story begins in 1954 when he goes to collect his grandfather’s brother, just released from prison for collaboration during World War II. Several parties believe he’s hidden some Nazi gold, and they want it.

Rullier’s supporting cast have a pleasing ethical ambivalence. They do what they do, and believe what they believe, but he condemns no-one, be they traitor, gangster or soldier, and some minor characters have great affectations. A would-be gangster recites his film fantasies as he goes about his work, incompetent government agents maintain a sneering superiority, and the old man in the final story is unapologetically bigoted. Rullier ensures his carefully researched period settings resonate, and he’s noted in interviews that France’s colonial history is one now largely swept under the carpet, making Indochina in the late 1940s an attractive setting.

By the Numbers works because it may be enormously influenced by Tintin, but it winds its own path, and these adventures can be read and enjoyed knowing or caring nothing about the influence.

The opening two parts, a self-contained story, have been previously available in English as By The Numbers: The Road to Cao Bang as part of Humanoids’ short lived partnership with DC in 2004.