Review by Frank Plowright

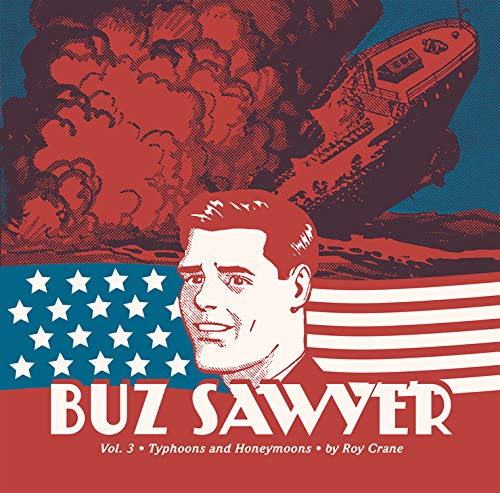

Common to most newspaper adventure strips from the 1930s onward was the idea of the rugged hero having a glamorous girl in every port. One, however, would be the special one, in Buz Sawyer’s case Christy Jameson, and strip creators would tease readers about their eventual marriage. Roy Crane and Edwin Granberry manage this very effectively in Typhoons and Honeymoons, although it should be noted there’s a reason for the title. Does Buz get married? If so does he marry Christy? Or is it someone else’s honeymoon referred to in the title? Although categorised as adventure, for weeks of daily strips at a time the writers would run with content nowadays almost exclusively consigned to romantic comedies. There was the obvious marketing aim of attempting to have the strip appeal to more women, and one nicely conceived subplot has Christy taking a job working at the same company as Buz, but crucially while he’s away, and in the meantime learning from others what a womaniser he is.

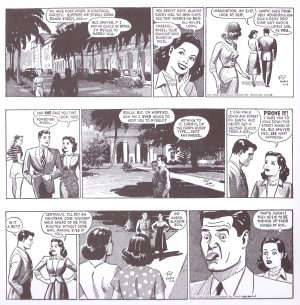

Crane also moves the continuity away from Buz for considerable periods, confident enough that readers will follow him around the supporting cast and establishing people who’ll play a part in the adventure to come. An additional reason might be to give himself less work, as some of these sequences look to have the hand of another artist, most likely to be his assistant Hank Schlensker. The art is still polished and attractive, so this is just case of minor differences in style. Later in the book other extended sequences have Buz absent, one with Christy heartbreakingly tense, and a comedy interlude with Rosco Sweeney less satisfying, but heartwarming and gorgeously drawn.

Eccentricity is a key feature, keeping readers guessing and providing colour. It also preserves the strip for the ages, whereas some of the mysteries conceived in the 1940s are no longer so mysterious. The first real adventure occurs on an island in the Atlantic where Buz is tasked with figuring out where arms are hidden and how they’re transported. Most readers will figure that early, but the strange and unpredictable villainy of Harry Sparrow and Hammerhead Gool ensures the sequence is still immensely entertaining. Other stories take Buz to India and to Africa, Crane and co-writer Edwin Granberry extend three stories over the entire continuity from mid-1947 to mid-1949, but while that may seem few for a daily newspaper strip, they’re extended naturally for the most part and avoid repetition. All these years later they’re still gripping, the traps ingeniously conceived, and the character touches sometimes of their time, but believable.

A company director taking all the credit for someone else’s work remains topical, but Buz looking after the interests of an oil company interfering in a foreign land no longer seems as harmless, and some of the attitudes toward women are prehistoric. More positively, and definitely ahead of the times, when Buz is in Africa the local people are not caricatured, but, with one slight lapse toward the end, drawn with dignity and respect. Attempting to break down the artistic contribution is a job for the experts, but Crane is definitely responsible for the panel designs and a lot of the drawing, which is beautifully composed and evocative, an example of quality surviving the decades.

The book ends by reproducing fourteen Sunday pages in colour spanning 1945 to 1963, and featuring Rosco Sawyer. These aren’t Crane’s work, but are nonetheless very elegantly drawn if not first rate gag strips. The continuity from 1949 to early 1952 follows in Zazarof’s Revenge.