Review by Ian Keogh

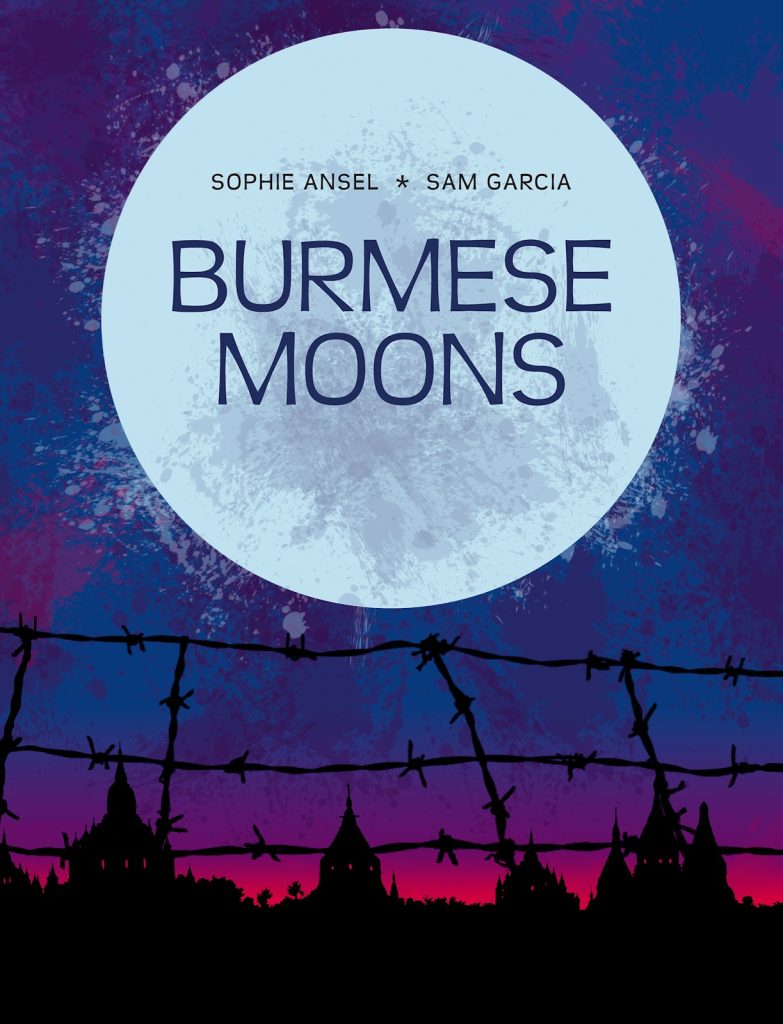

What was once Burma is now Myanmar, currently known the world over for a secretive military dictatorship, the attempted extermination of the indigenous Rohinga people for being Muslims, and latterly sporadic local uprisings. Not that the country has ever been a bastion of freedom since independence in 1948, as Sophie Ansel explains as the story unfolds.

Burmese Moons begins in the 1980s and Thazama being raised among the Zomi people in the Northern jungles. An early joy is the reduction of World War I to a tribal myth, but Ansel’s primary purpose is to consider how the country progressed as Thazama ages. Student demonstrations in 1988 were violently quelled with no concern for human life, which had always been the tradition, and persecution begins when soldiers arrive in Zo chasing those who’ve fled the capital. Thazama and his friend Moonpi believe they have no choice other than to leave in order to find work and send money back to their village to bribe soldiers. If they stay they risk being co-opted into the military or killed without a thought.

Ansel is a journalist who’s spent plenty of time in Asia, both in Myanmar and interviewing those who’ve escaped elsewhere. Her conflation of their stories in Thazama is an impassioned view of history intended to arouse anger, and the consistently harrowing circumstances should do so. Personalising situations allows for greater empathy with the people things happen to, and even the small indignities raise the hackles, but a minor failure is including dense pages of background information several at a time rather than via a more reader friendly alternative.

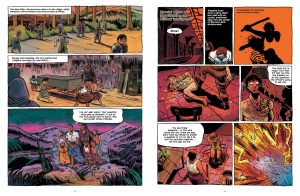

Instead of drawing the soldiers as normal people Sam Garcia makes the small change of giving them the pointed carnivorous teeth of predatory animals, which is extremely effective. He’s called on to draw some grim material, and even though he’s nowhere near as explicit as he might be, the catalogue of atrocities means this is no book for the fainthearted. However, his purpose is to awaken via documentation, and shock should be a natural result.

Through Thazama we see revolutionary ideals, torture, the prison system, and how escapees fare, along with their aims, as the persecution hardly ends with jail distant. The wonder throughout is how so many Burmese working for the system are able to disassociate themselves from such murderous persecution of others. It’s briefly addressed with a prison guard reflecting it’s only work, and a strange point well made is prison cells providing the only locations for people to speak freely within Myanmar.

Sadly, the exploitation hardly ends with Thazama escaping jail, and Ansel ensures the pernicious Malaysian treatment of refugees is also highlighted, a system with equal disregard for human life including state sponsored slave trafficking. Even though there are moments of hope and relief, Burmese Moons isn’t intended as comfort reading, but as chronicle of man’s inhumanity. It’s terribly, terribly sad, but with the purpose of informing and enraging. Once a story’s told it’s there to be spread, and this will open many eyes