Review by Rob Walton

Pathos and tragedy are at the forefront of Osamu Tezuka’s seventh and particularly moving volume of Buddha: Prince Ajatasattu.

Prince Ajatasattu is the son of Buddha’s old friend and patron, Bimbisara, king of Magadha. The story opens with Buddha’s long promised return to Magadha where he finds Bimbisara plagued by the foreknowledge that the prince will kill him on his 41st birthday, as prophesised by Assaji in Devadatta. The king is now 36 years old and has five years left to live. Ajatasattu, on the other hand is adamant his father has been duped. He loves the king and would never hurt him. He sees Buddha, on the other hand, as the cause of his father’s suffering and resolves to kill the saint.

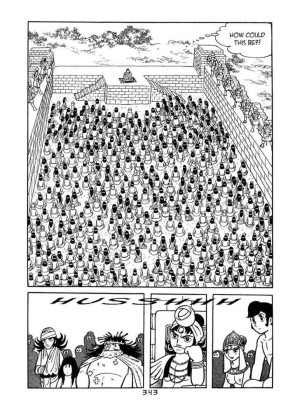

Thus the supreme tragedy begins to unfold, and the lives of many characters are challenged and pushed to the limits. Devadatta’s ambition once again seeds conflict, and Ananda is sent on a deadly mission by the Buddha to find Assaji’s successor. The villain Ahimsa pursues Ananda and Buddha like a wolf, not resting until his jaws are at their throats. Love is tinged by death, with consequences both profound and tragic. The caste system comes under scrutiny and challenge as the prejudices and suffering of the characters are revealed.

The catalyst for volume eight’s conclusion is Brahman’s return, as he shakes Buddha out of the complacency of his cozy life in Deer Park. Buddha resolves to return to Kosala, reuniting him with his mother, wife and son, and bringing him into a final confrontation with Prince Crystal that will decide the fate of the people of Kapilavastu.

Throughout it all, Buddha confronts the suffering of the characters with a prescription of a life affirming acceptance of our own self-inflicted wounds. As Buddha’s wisdom grows, so do his earlobes, and by the end of volume seven he has assumed the familiar characteristics of the Buddha’s iconic visage.

There is less noticeable corny humour in this volume than in previous ones, but it neither distracts nor detracts from the seriousness of the narrative. As always, the humour lightens the tone of a story that could otherwise have been marred by an overly serious and heavy-handed treatment. When Buddha refers to himself as a physician, he is suddenly caricatured as Tezuka’s maverick doctor, Black Jack. These are welcomed moments of levity that keep the narrative moving.

The overall impact of this volume may vary from reader to reader, but the tragedy that occurs and the consequent tragedy it sets up, both in the lives of the characters and kingdoms they inhabit, is undoubtable. Five stars may be too few for this volume.