Review by Ian Keogh

An advantage the graphic novel has over the serialised comic is the ability to create an effective mood, and Jean-David Morvan certainly sets that over the opening twenty pages of Bramble. We see a strange looking, almost bald man leave a country community, and it’s only when he arrives in a retro-designed city that we realise he’s a giant compared to the usual citizens. He’s befriended by an old woman, and at first we’re unsure whether she’s the corpse later being studied by police Captain Mornières.

Mornières is established as a diligent and honest man, qualities that earn him contempt at home and at work. Were he still a teenager this would be a coming of age story, but the equivalent happens to him much later in life as he’s awoken to his place in the world. The giant knows it from the start, and the viewpoint occasionally switches to his view of the world, enabling an understanding of why he’s possessed of murderous impulses, although the full explanation is a while in coming.

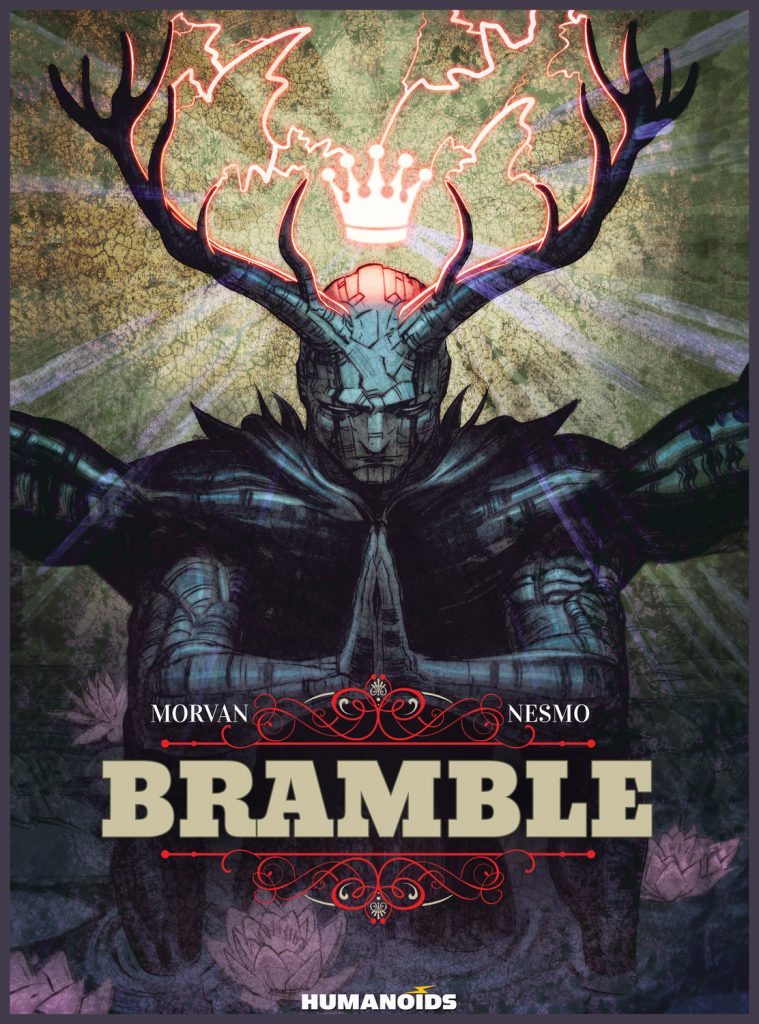

Bramble is eventually revealed as ecological ideology, a fable foretelling the dangers of nature and civilisation not remaining harmonious. As it continues, however, more and more devices from superhero comics work their way in, although this is prevented from being obvious by Nesmo’s eye-catching and jaw-dropping artistic vision.

As is common for European creators, Alexandre Nesme uses a pseudonym for his professional career. His art is deliberately disorienting, rarely adopting the viewpoint of drawing someone directly face on. We see people from above, from below, from the side, sometimes in diagonal panels and frequently as if through a fish eye lens. It’s disconcerting initially, especially the abrupt switches into how the giant views city inhabitants and structures, but Nesmo’s is a world that sucks in like a whirlpool and the visual artifice combines to create a mood of surreality, as if everything is a wild dream. It’s a view reinforced by the changes made to everyday objects. The only car seen is a version of a classic 1930s Bugatti, distorted by Nesmo into a functional new design, and he mashes New York tenement blocks with Parisian subways. It’s a similar sort of atmosphere to the visually stunning French movie City of Lost Chidren, created by former comic artist Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunot, and it’s not too great a step to consider Bramble making an equally good movie.

In fact, despite the art looking amazing on the page, there’s a case to be made for Bramble working better as a movie because Morvan’s plot deals very much in archetypes in what’s a depressing view of humanity. By the end he’s surpassed the bleakness of Judge Dredd’s outlook. There’s certainly no obligation for all graphic novels to be cheery, but don’t read this if you’re looking for a light pick me up. Furthermore, the revelations occur at roughly the halfway point, after which the plot moves into more ordinary action thriller territory, and it’s not as interesting. There is, however, enough wonder about the art and enough intrigue about Bramble to begin with to make this worth a look.