Review by Cefn Ridout

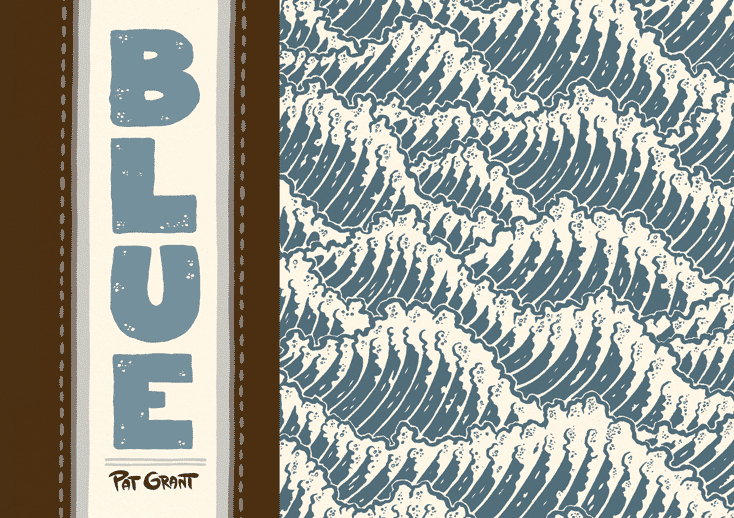

Ostensibly a coming-of-age tale of three Aussie teens wagging school in search of the perfect wave, Pat Grant’s debut graphic novel Blue emerges as a thoughtful parody-cum-allegory that explores the roots of beachside bigotry and aggressive anti-immigrant localism in Australia’s coastal communities.

Set in the fictional seaside suburb of Bolton, the book opens with its browbeaten protagonist, Christian, bemoaning the day when everything changed – when he first encountered the ‘blue people’. On that day, Christian and his deadbeat surfing mates traipsed along the railway line to a fabled cove and its legendary swell, only to get sidetracked by the chance to see a dead body. The corpse, or what’s left of it, turned out to be that of a newly arrived blue person who had been hit by a train the previous night while seeking refuge.

The deceased was one of the alien-like blue people who had begun landing on Bolton’s shores in ramshackle boats in growing numbers, challenging the bolted-on attitudes of the locals. Yet the area had already witnessed more than a few changes in its time: from a pristine surfing paradise paved over with a parking lot and accompanying tidy town, to a graffiti-smeared, boarded-up migrant ghetto with hardly a local face in sight.

Grant starkly juxtaposes a rose-tinted view of Bolton’s past with an unflattering portrait of its present in a confronting ‘before and after’ tableau, which reveals the deep alienation felt by his less-than-Christian narrator. It’s a brave sequence that risks being misunderstood, but underscores the book’s delicate, if not always successful, balancing act between illustrating how intolerance can seep into and define a tightly knit community’s identity and sidestepping an overtly finger-wagging liberal stance.

Despite the book’s downbeat view of race relations in Australia, exemplified by Christian’s Sisyphean job whitewashing walls covered in blue graffiti, Grant hints at belated stirrings of self-awareness in the book’s closing pages. Back in the present, Christian fleetingly concedes that perhaps the locals, unable or unwilling to get along with their new neighbours, gave up on Bolton, contributing to its decline.

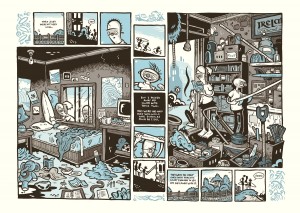

While its broader political ambitions could be better woven into the storyline, Blue’s strengths lie with the impeccable craft and conviction Grant brings to the proceedings, especially the spot on evocation of a happily misspent youth, which fizzles with manic energy, false bravado and pungent humour. And Grant’s keen ear for the colloquial banter of his youth and fondness for his boofhead creations ensures that they aren’t easily dismissed as racist caricatures, but reflect Australia’s vexed attitude to immigrants.

Visually, Blue is a triumph. The expressive, stylised artwork and two-colour palette enhance the book’s themes, while the lovingly detailed backdrops create a persuasive, if slightly surreal, sense of place. If the tentacled aliens are a mildly threatening shade of blue, Grant’s human characters fare little better, being depicted as a motley parade of grotesques, with rubbery limbs and oafish features that match their IQ. Grant also stretches the grammar of the medium, best seen in the cleverly compressed introduction to Christian as he surfs back to the fateful day when his world turned blue.

Blue is rounded off with a lengthy, wayward yet passionately argued essay on the under-appreciated history and significance of Australian surfing strips, perhaps the country’s true vernacular comics, alongside a revealing insight into the autobiographical details that underpin the story.

If, as Grant believes, cartooning is akin to performance art, with similar physical and creative demands, then Blue is a bravura opening night, heralding the arrival of a bright new talent whose next work will be keenly sought out.