Review by Frank Plowright

With this third volume Ta-Nehisi Coates brings his fatally flawed opening interpretation of the Black Panther to a close, and the overall tone is barely different from the previous two books. While not espousing Jack Kirby’s as the sole valid method of telling a Black Panther story, one imagines he’d have knocked out the same plot over two chapters. It takes Coates a dozen. Even Don McGregor, the most verbose and introspective writer associated with the character before Coates, would have moved matters further quicker.

As the book opens there has been some progress. In book two the Black Panther dealt with one of the revolutions being fermented in Wakanda, and his sister Shuri exited her coma having benefited from the experience, now being the repository for Wakanda’s collective history. What follows is an episode and a half of utter tedium as all parties discuss the philosophy and precedent behind what they’re intending to do. This is underpinned by a sensible purpose as Coates advocates conversation in preference to violence, which is a novelty for what’s ostensibly a superhero graphic novel. What use, however, is conversation with those who are not reasonable people? Those who seek power for its own purpose? That battle occurs in the penultimate chapter. Will it finally provide the spectacle the series so desperately needs?

Not really. There is some action, but talk again predominates, with the themes Coates has hammered home since the start entwined via caption: the past cannot be erased; words have power; the nation is strength; the throne carries a burden of responsibility and hand-wringing is the purpose of life. That last one’s a lie, as it’s not what Coates explicitly espouses, but it might as well be from what’s presented. Everyone is so caught up in their own guilt and impotence that the entire tone is supercilious and dreary, sucking any possibility of entertainment. Ironically, another theme of Coates’ run is the importance of stories and mythology. He seeks to educate, but eradicates the joy from learning, and provides barely any narrative imagination to A Nation Under Our Feet.

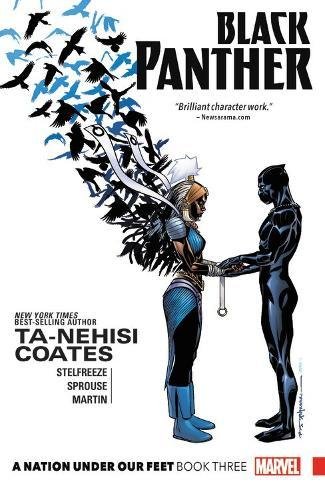

Once again, the art lifts the overall value considerably. Chris Sprouse and Brian Stelfreeze, the artists of the previous volumes, share the pages, with Stelfreeze more likely to embellish his panels with detail, and Sprouse the moderately better storyteller. They merge seamlessly despite differences in approach, yet neither is good enough to bring this to life. Stelfreeze, so strong in characterising Wakanda as a nation in the opening volume, pulls back a little here, and his most notable visual contribution is a great design for Shuri, as seen on the cover.

Once Coates is done we move back in time to material written by Jonathan Hickman, originally part of the Avengers series, in which the Panther first consults his predecessors. It’s an interesting contrast to Coates’ work as it equally deals with the methods of the past as represented by the earlier Black Panthers, and introduces the events permitting Coates’ story. Narratively it might have been better placed opening the first volume of A Nation Under Our Feet.

Someone trying something new that doesn’t work is infinitely preferable to recycling the past. The King has new clothes. Are they worth wearing? As an alternative to the three collections as originall released, the bulky paperback A Nation Under Our Feet collects the entire twelve chapters.