Review by Frank Plowright

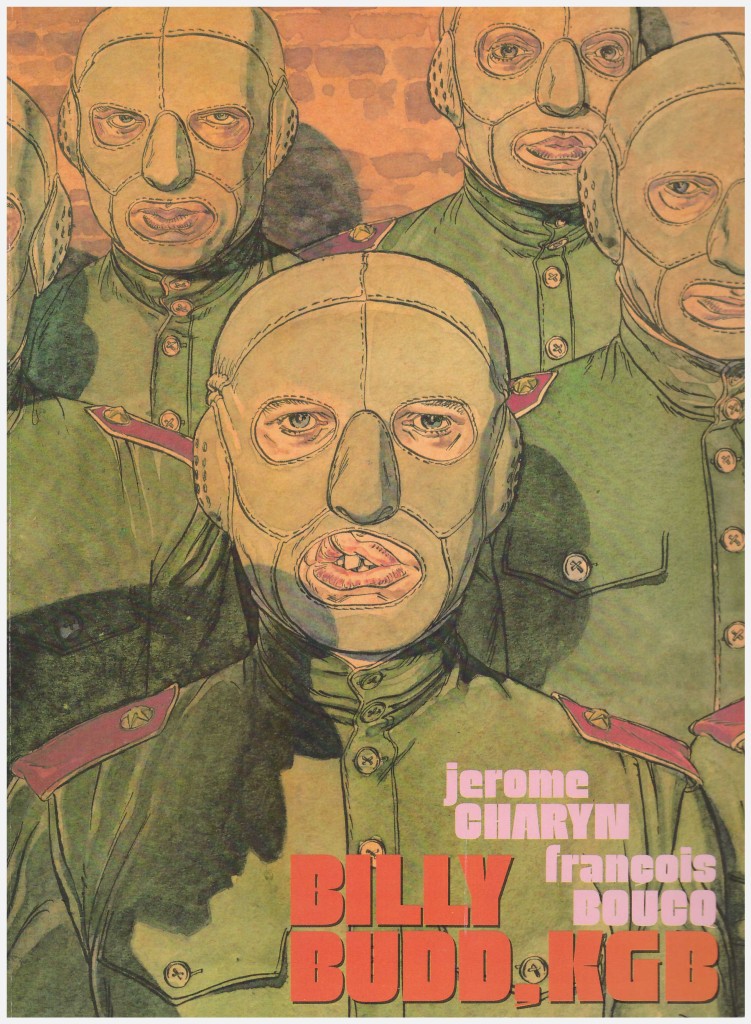

Billy Budd, KGB was published in the dying days of the Cold War, and the original French edition was titled Devil-Mouth. This title of this translation instead references passing whimsy inside, creating a distracting joke. It’s the identity our protagonist is given when his training has been completed and he’s sent to the USA of the early 1960s. Attempts to tease out further comparisons with Herman Melville’s final novel come up dry.

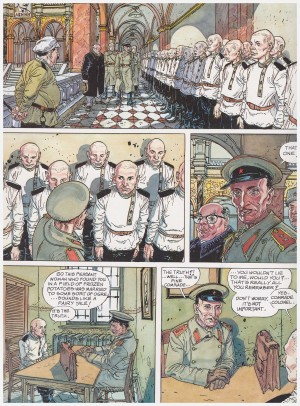

The book is a dispiriting condemnation of Soviet systems and a more subtle critique of the ideological opposite, the USA. Yuri, an orphaned youth with a disfiguring hare lip is selected for training as a spy by the Russian army. The notion of a system that orphans children training them to become the cause of the next generation’s orphans is depressing, and the training is brutal, excessive and comprehensive. Individual identity is subsumed by the wearing of head and face masks as illustrated in the cover. The training occurs in what was once a monastery, with one of the monks remaining as a teacher. Yuri experiences odd dreams, may have some psychic ability, and he also receives secret religious instruction from the remaining monk

Once he’s deemed to have absorbed all that’s required, Yuri’s hare lip is surgically adjusted, he’s given the Billy Budd identity, and shipped to the USA to blend in and await instructions. He’s deliberately immersed in the worst of New York, his job among the high scaffolding of the skyscrapers the only alternative perspective. It’s here he makes friends among his native American co-workers.

The myths and spiritualism seemingly intended as the heart of the story are somewhat sunk among the action thriller tropes, but that material sustains the tension enough to create an interesting narrative over three chapters.

Writer Jerome Charyn uses no thought balloons or narrative captions, so our only insight into Yuri/Billy’s thoughts and feelings is what’s presented, and no matter how good an artist François Boucq is (and he’s very good indeed), an emotional distance is created. Charyn presents very few definitive statements about Billy, as he takes a path that rejects Soviet orthodoxy yet doesn’t embrace the obvious alternative. His key defining scene is when he’s required to investigate a fellow Soviet agent, now comatose, during which he receives an unwanted insight into the casualties of ideology.

Billy’s story has a cinematic quality, and that’s provided by Boucq’s considered layouts and immense ability to render haunting visual characterisations. His attention to architecture, both decorative and mundane, is also inordinately impressive, but the colouring is very much of its era.

This is far more satisfying than Charyn and Boucq’s previous collaboration The Magician’s Wife, and it’s hoped the forthcoming Dover Press edition improves on the colouring. They might also want to try for a moderately more naturalistic translation.