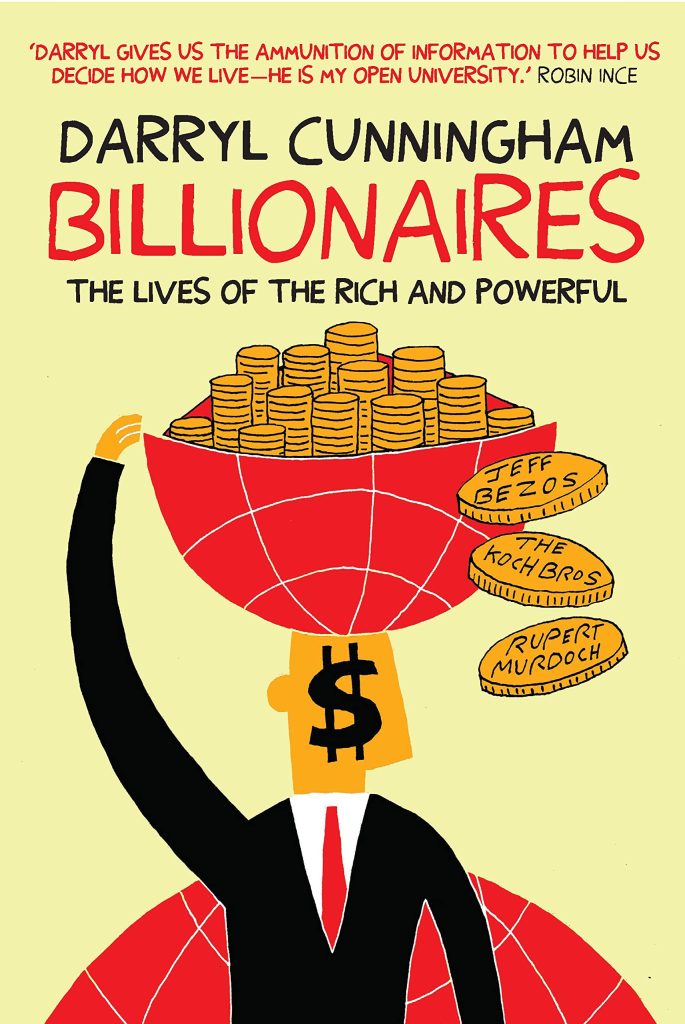

Review by Frank Plowright

Darryl Cunningham begins Billionaires by drawing a comparison between the current era of wealth and the final few decades of the 19th century when the massive gulf between richest and poorest was previously at its widest, and spotlights four people over three primary industries. Rupert Murdoch’s fortune was amassed through newspapers while Charles and David Koch’s money comes from oil processing then diversification. Jeff Bezos via his creation of Amazon represents a less traditional income stream, and provides further contrast by having worked hard at starting his own business instead of expanding inherited and already successful companies.

Given that the people he’s writing about are extremely wealthy and surely employ an army of lawyers, Cunningham’s usual habit of referencing his sources is even more scrupulous than usual, occupying four pages at the end of Billionaires. To those unfamiliar with the subjects he offers surprises with just the basic background information. Murdoch, for instance, studied philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford and campaigned for a Labour candidate at the 1951 election, while Jeff Bezos’ childhood fixation extended to a cameo role in the 2016 Star Trek movie.

What are the common threads between the spotlighted billionaires who’ve made their fortunes in different industries? Several shared characteristics occur, most obviously a dislike of anyone other than themselves making money. Each has inflated their own bank account by creating appalling working conditions or clamping down on workplace activism. The latter is highlighted most in Murdoch’s case where the policy was actively encouraged by a right of centre UK government using state assets to protect private business, violently if necessary. They’re also smart men, and the least surprising shared characteristic is that the wealthy spend vast amounts of money to advance their own interests, which rarely coincide with the interests of the majority. The Koch brothers who inherited a company already worth millions, fund “independent” think tanks whose advice includes abolishing a minimum wage and rent controls, and organisations producing reports discrediting the science of climate change.

Despite a litany of crimes perpetrated by the companies they run, the worst that happens to the chiefs is some men rich beyond the wildest dreams of some nations, never mind most people, temporarily lose some money. The political and legislative system in the UK and USA is shown as stacked against the best interests of the many, with negotiated settlements in the USA mitigating loss. If someone has the wealth to fund messages ranging from outright false to having a dubious relationship with truth, and to discredit opposition, then wild beliefs will take hold among enough people to have greater influence.

Cunningham has no doubt that aggressive policies of deceit and lies vigorously pursued in self-interest have resulted in the quality of life for ordinary people diminishing in the 21st century. The question remains whether the greater blame lies with the sharks or weak and mealy-mouthed who enable them. Billionaires is diligently researched and concisely presented, but unhappy reading for anyone believing no-one is above the law.