Review by Frank Plowright

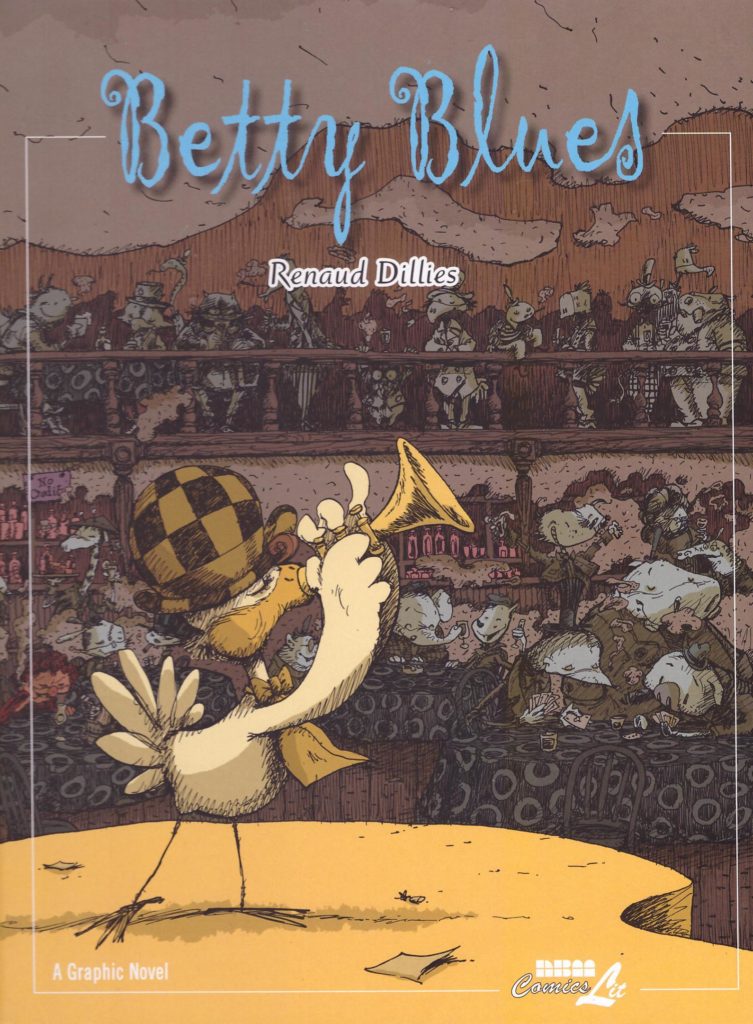

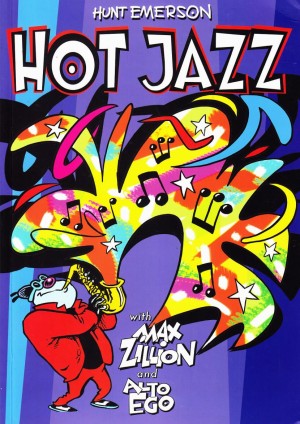

There’s a charm to the cover illustration of Rice Duck on stage tooting his trumpet, but a truer indication of what awaits inside is given by the darkened background, in which assorted characters merge into one another and too many squiggly lines make it difficult to work out what they are. Betty from the title can be seen slumped at the far left, picked out in red. She’s Rice’s girl, at least until she gets the offer of a crate of champagne from a suave stranger. That breaks Rice up. What’s the point of continuing without her? He tosses his trumpet from the bridge and takes the morning train to nowhere.

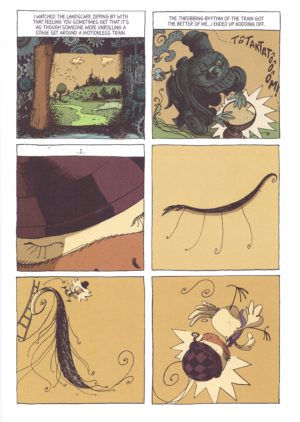

Perhaps it’s intended as a visual metaphor for jazz improvisation, but over a crowded opening sequence the eye meets a jumble of shapes and scratchy lines, where it’s difficult establishing people, never mind features. Thankfully, following that Renaud Dillies tones down his panels, giving them a focus. He’s strongly influenced by the surreal transformations of early animation, imaginatively twisting the train on the sample page, which heads into a dream sequence, and much of Rice’s subsequent waking moments might almost be dreams. When the looseness of the art avoids messiness Dillies produces some nice panels, working well with silhouettes at night, and incorporating a lot of 1930s imagery and themes as Betty Blues continues.

Dillies paints his characters broadly in what amounts to a fable about the evils of big business, of profit before humanity, and how the little guy never has a chance. Betty is seduced by a slug as Rice rediscovers what’s worthwhile in the world. There’s little subtlety about the methods, and the only real surprise comes with the ending, which matches the mood cultivated from the start. It’s slow, at times ethereal, and certainly heartfelt, but Betty Blues is only destined to captivate the few, not the many.