Review by Ian Keogh

In the 1980s Watchmen creators Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons signed a contract that would return ownership of the characters they created should the book ever drop out of print. It never has. Moore was originally open to producing a prequel, but eventually concluded it redundant. He’s refused all offers since, and DC held out hope for over twenty years in the face of Moore’s public pronouncements concerning his views on their way of doing business, although Gibbons has been more ambivalent. Among many other matters, Watchmen dealt with murky ethics, of compromises in the name of right, yet DC found no shortage of top class talent willing to work on these prequels.

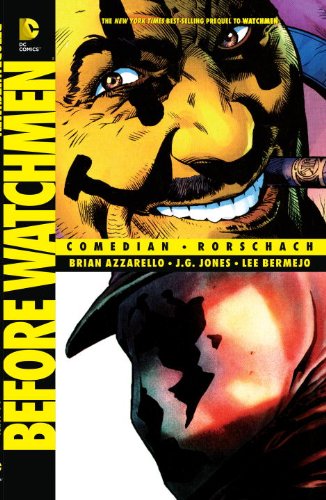

It’s fair to say that their nihilistic, ruthless and uncompromising characters ensured that of all the Watchmen cast, the Comedian and Rorschach resonated most with the readership. It therefore makes sense to have their stories combined here, but Brian Azzarello’s use of them barely transcends average. It’s odd, because his work on 100 Bullets surely suggests that Azzarello applying himself could produce something more original despite theirs being the most completely revealed biographies in the original graphic novel.

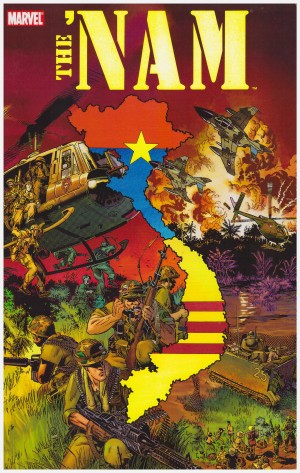

Azzarello’s focus on the Comedian slots his moral ambivalence into the ideal circumstances by concentrating on his 1970s involvement in Vietnam. The broad picture, if not the day to day detail was thoroughly presented before, so to avoid entirely retreading old ground Azzarello adds a political dimension, of the Comedian hanging out with the Kennedys in the early 1960s. This is the best aspect, resonating in the opening and closing chapters, but between them we have a discursive four chapters set primarily in Vietnam that tell us nothing and might as well be one of those old Punisher comics recounting his Vietnam days. It’s that lacking in inspiration. Azzarello attempts to convince us that Vietnam was the ultimate screw that formed the Comedian’s worldview, but that’s at odds with what was previously established. Credit, though, for a well-conceived final page.

J.G. Jones’ art works in some places, and is lacking in others. His anatomy lets him down for someone aiming for naturalism, and his characters often lack weight. There’s a scene late on with the Comedian leaning against a bar, but looking as if he’s just about to float off.

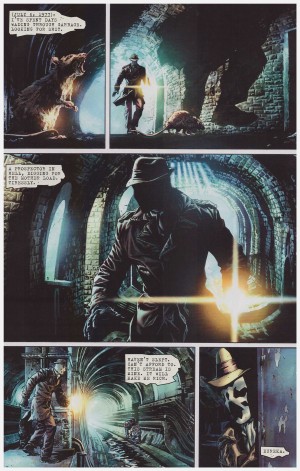

Never mind, this is a double feature after all, and Rorschach’s tale is slightly better. As this is the younger, unformed Rorschach, Azzarello has some leeway. At this point he’s a crime fighter lacking patience and capable of error, and a man yet to make irrevocable choices in his life. Azzarello is more comfortable here, supplying a decent enough crime story, although again somewhat artificially extended, dangling the possibility of love and an entirely different life path. Surprises are few, and the deliberately sadistic moments overstated, but it’s served well by Lee Bermejo’s scuzzy, rain-sodden New York of the 1970s.