Review by Karl Verhoven

As the story of Arkham City was concluded in the previous book, DC take the unorthodox step of leaping back to the days when it was still being constructed, with Karen Traviss coming on board as writer. Furthermore, the format alters. We still have the artist changing every three chapters, but instead of each illustrating a self-contained story, there’s a thread running through most of the book.

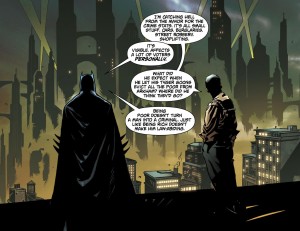

A poor area of Gotham was cleared to enable the construction of Arkham City, and this social cleansing didn’t sit well with some among the disenfranchised. A new villain named the Bookbinder takes it upon themselves to take revenge, in a manner more typical of Batman ’66 choosing to send elaborate literary clues to Commissioner Gordon. A secondary problem is that demolition has moved a lot of crime from a previously confined area into the wider Gotham.

Traviss’ script takes a long look at social engineering and the political justification for it. Councilman Grove’s plan is to be “tough on crime by being touch on the roots of crime. We’ll make Gotham a no-go area for anyone who isn’t a productive, literate, numerate, community-minded citizen”, as Traviss perhaps overplays her hand. Overall, though, she produces a decent Batman story about political and judicial corruption, just not one very likely to thrill buyers expecting a villain-fest tying in with the Arkham City video game as the remainder of the series has been.

Of the five artists used, it’s Beni Lobel that’s the most distinctive, with a scratchy noir feel to his pages, but he only illustrates the abrupt finale, and unfortunately doesn’t bother maintaining visual consistency with regard to a prominent character. All the others artists are competent, but none particularly stands out. Most importantly, in a story featuring very few costumes, Ricardo Burchielli, Christian Duce, Federico Dallocchio and Tony Shasteen are all comfortable illustrating ordinary people in day to day environments.

Given Traviss was building towards something here, that she obviously wasn’t given the opportunity to supply a more considered ending is a shame, and weakens the entire book. On the other hand where she was heading is not concealed, and the Bookbinder is a more a function of the larger picture. Their identity is broadly hinted at from early on. Structurally, a consistency renders this the best of the four Arkham Unhinged books, just not fitting the pattern of the remainder.