Review by Graham Johnstone

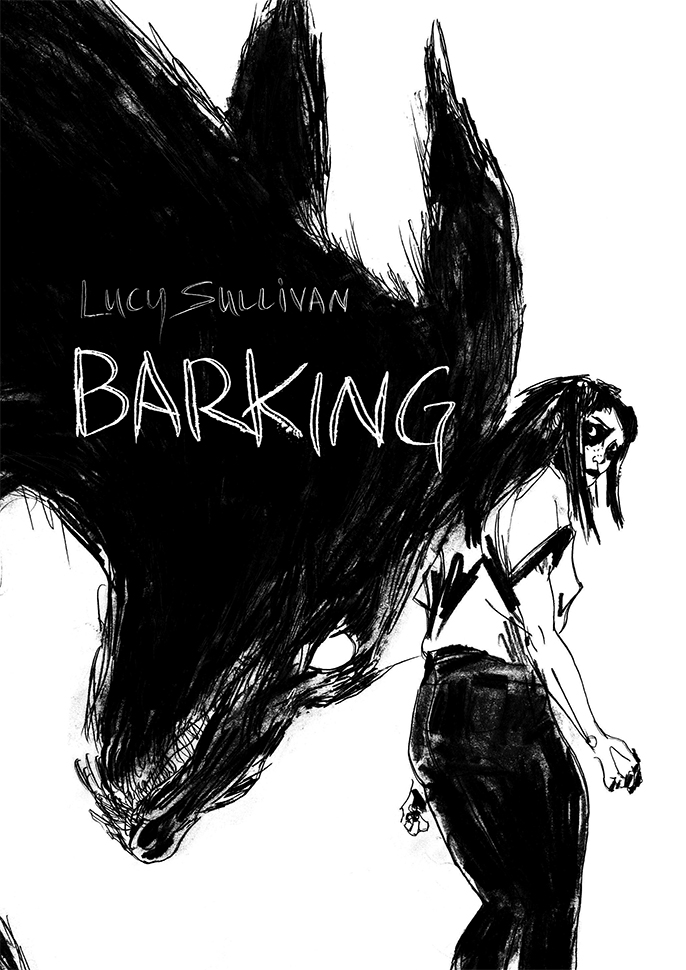

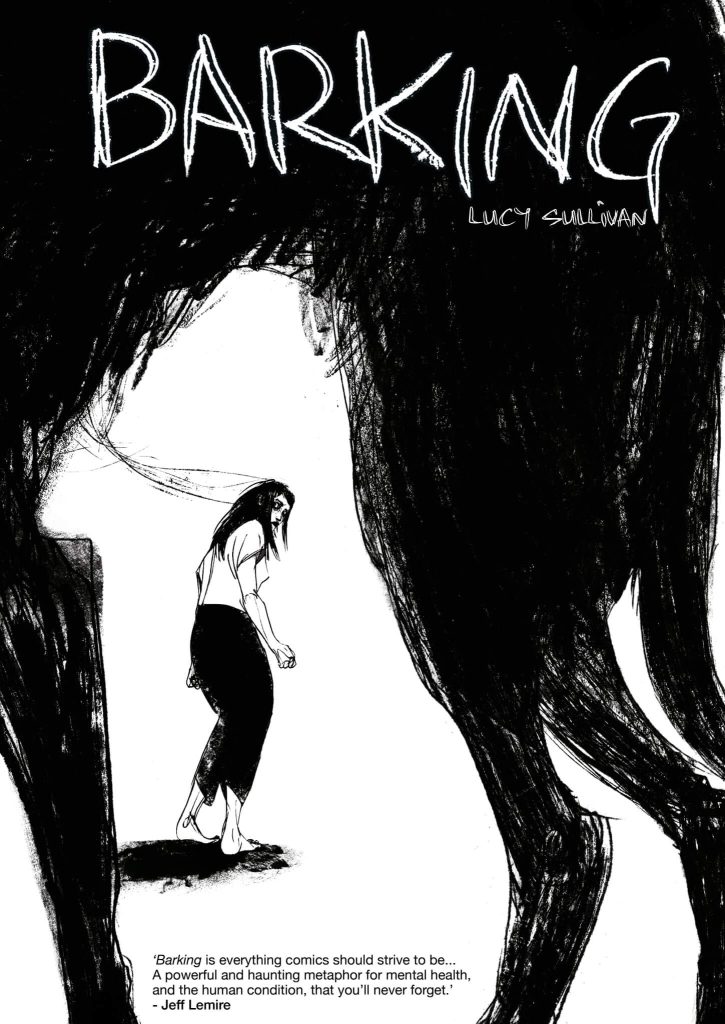

‘Barking’ is taboo slang for mentally ill, and also evokes ‘the black dog’, an enduring symbol of what’s now understood as clinical depression. Together these provide a suitably striking title and visual motif for Lucy Sullivan’s graphic novel debut.

Sullivan’s credibility to tell this story is endorsed by Nick Abadzis in an illuminating foreword, and Sullivan’s afterword elaborates further. Others have documented mental illness through comics, notably Darryl Cunningham’s Psychiatric Tales. In contrast to the latter’s calm objectivity, Sullivan starts with intense subjectivity, sucking the reader into her character’s mental maelstrom.

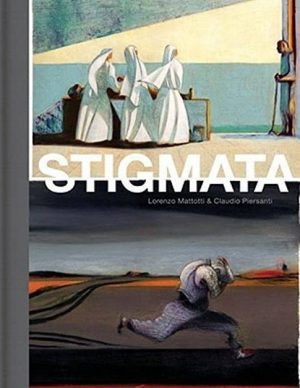

Already an illustrator/animator, Sullivan is not the first to turn to comics to tell a more personal story, and approaches the form unburdened by conventions like panel grids, and overdrawing in ink. Sullivan’s pencilled pages capture the directness and vitality of life drawing, amidst visceral mark-making suggestive of psychological turmoil. Few have brought these techniques into comics, the closest perhaps being Lorenzo Mattotti’s swirling and slashing pen lines on Stigmata, but even that seems mannered compared to Sullivan’s scribbled, scored and smudged surfaces. She has restraint too, knowing when to omit backgrounds, and mirroring the generally calmer mood of the second half. Sullivan may ignore the conventions of comics, but artfully uses the form – including montage effects, juddering ‘camera movements’ and barrages of word balloons – to powerfully convey an overloaded mind.

The story starts with Alix Otto on a bridge, looking over the edge. She’s arrested and institutionalised, leaving her confused and frightened. Sullivan lets us see this from the inside. If it’s sometimes hard to distinguish present realities from imagined and remembered scenes, that plausibly reflects Alix’s experience. A series of short chapters each start, like official records, with a typed date and time, so poignantly counterpointing Alix’s jumbled thoughts and feelings. The aforementioned black dog is a recurring presence, and conversational foil for Alix: part critical parent, part abusive partner.

Decompressed storytelling, moving slowly through the first evening, ratchets the tension. By the book’s midpoint we’re only three days in: presumably the ’72’ mentioned by care staff, meaning an assessment period. Thereafter the story moves from shock to adjustment as Alix explores her new world and its inhabitants. Sullivan also shifts mode from psychological realism to classical mythology. A journey into the underworld, climaxes in a posthumous face-off with her nemesis, so setting up resolution in the ‘real world’. It’s a powerful story, both intimate and epic.

Sullivan tells that story well. She’s able to turn from Alix’s disorientated subjectivity, to the system response, from policemen (mocking, threatening), to care workers (victim-blaming, and pushing religion). Of course, that could have been imagined without personal experience, but Sullivan enriches it with powerful details, like fragments from case files. Particularly striking are patient self-assessment prompts: “What shape is your feeling?” (featured image). The staff talk in shorthand, like ‘B.P.D.’. Readers may have to look it up, but will then recognise Borderline Personality Disorder’s symptomatic ‘intense unstable relationship[s]’ between Alix and damaged friend Rusalka. It takes careful reading to realise that some depicted events actually happened to Rusalka, but the traumatic effect on Alix is convincing. Turning to the mythological elements, Cerberus, the Hound of Hell continues the canine motif, but otherwise it’s overburdened by a miscellany of myth and mysticism. Nevertheless, what most readers will remember is a vivid and compelling evocation of mental illness, with trauma leavened by empathy and hope.

Barking is powerful as both mental illness testament, and graphic story-telling. The 2019 release opened doors for Sullivan, including a commission from Jeff Lemire, and 2024 saw a welcome reissue from Avery Hill.