Review by Ian Keogh

With Out of the Ashes the differences between older English language versions of Barefoot Gen and later editions come down to the nuances of the translation. The content of the first translated Volume Four from New Society now forms part of Life After the Bomb.

The book begins with Gen’s older brother Koji returning home from active service soon after World War II ended with Japan’s surrender, reuniting the surviving members of Gen’s family. Counterpointing that, American soldiers also arrive to occupy Japan, and Gen’s initial misgivings evaporate when he’s supplied with some gum. Any joy, however, is short lived as Gen’s family are once again evicted and suffer from severe malnutrition.

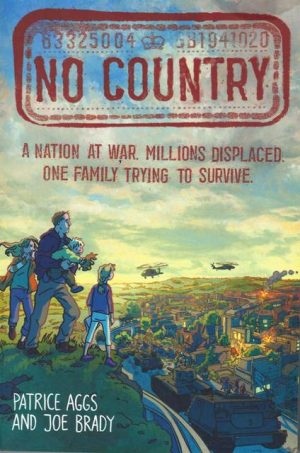

People’s capacity for cruelty has been displayed throughout Barefoot Gen to date, but when the characteristic is applied to a someone who features for a while, Keiji Nakazawa always rounds their personality out. So far that hasn’t been the case for the unpleasant Mrs Hayashi, but an eviction gives a reason for her bitterness. Despite that, this is a lighter volume than the previous three, as Nakazawa moves away from the horrific pain and disfiguration of the wounded, although there’s plenty of anguish as people have to discard pride in order to eat, and the callousness of children is constant. What’s brought out is that many ordinary Japanese people didn’t want war, yet suffered through it, and with the war over they’re still suffering, and as an occupied country there’s no complaining about their occupiers. It’s a situation repeated in many nations since.

Nakazawa’s introduction notes the stories related in Barefoot Gen either happened to him or to other people, and the stronger narrative of Out of the Ashes suggests more stitching has been applied. Whether that’s the case or not, it’s strong with plenty of tension, the centrepiece being concerns over Gen’s recently born infant sister. Compelling and tragic new characters are introduced, and the only certainty is Gen’s eventual survival no matter how bad the beatings he takes. The passing of time has made Nakazawa’s use of dreams unsophisticated, inserted for shock value both here and earlier in Life After the Bomb, and it remains strange to see tragic scenes drawn with comic exaggeration, but as before there’s no denying the power behind the story. It continues with The Never Ending War.