Review by Woodrow Phoenix

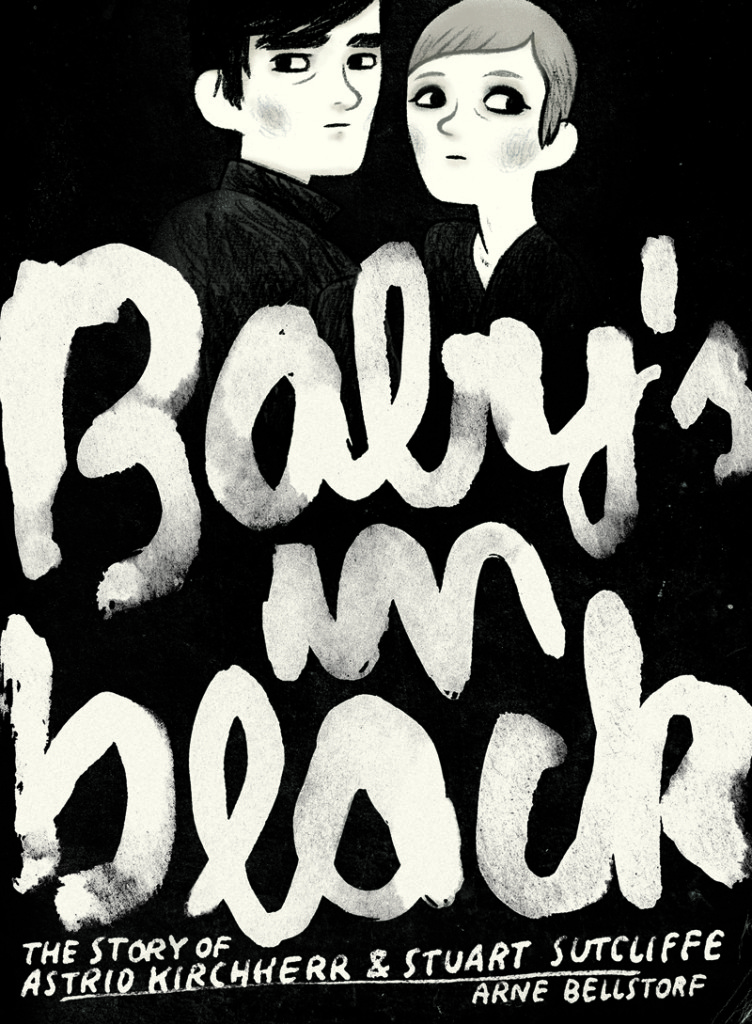

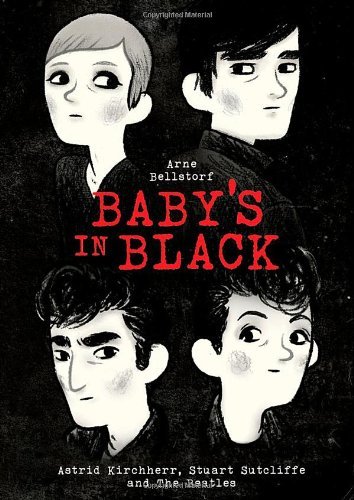

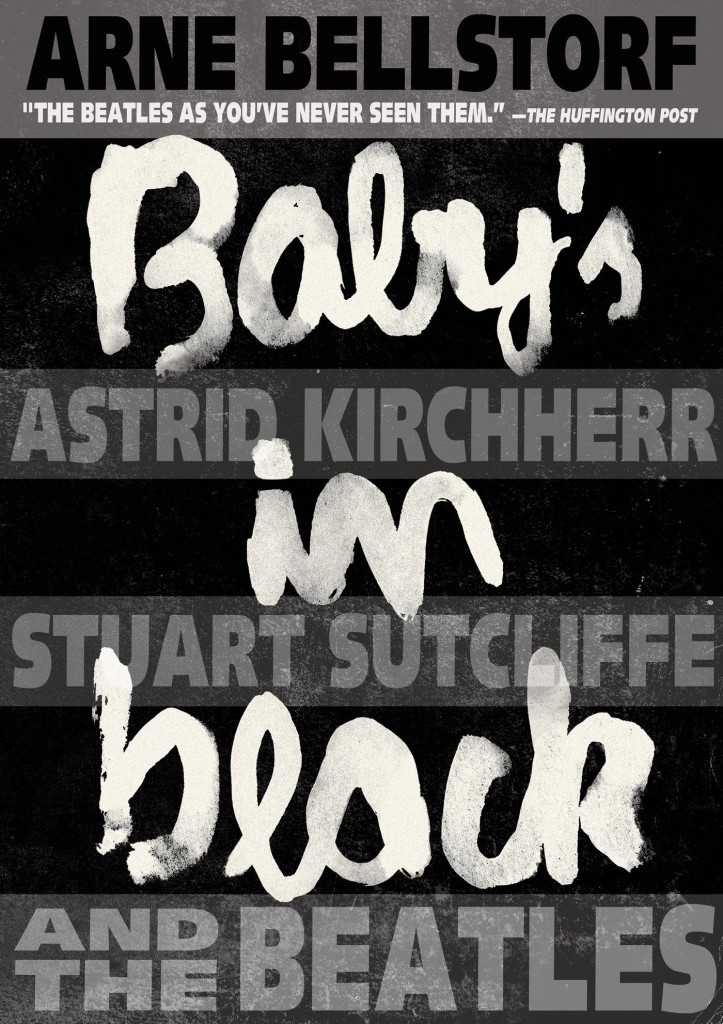

The story of the Beatles’ early formative time in Hamburg, as a five-piece band with guitarist Pete Best and bassist Stuart Sutcliffe, is the stuff of legend. Astrid Kirchherr’s photographs and her restyling of them into “moptops” helped propel them to stardom back in the UK. Kirchherr fell in love with Stuart Sutcliffe, who decided to leave the band and stay in Germany with her to become a painter, but their relationship lasted only a few months before Sutcliffe’s death from a brain haemorrhage. Kirchherr’s point of view, based on interviews with her, formed the basis for Arne Bellstorf’s graphic novel about the Beatles, Hamburg, Stuart Sutcliffe and the love affair that changed his life.

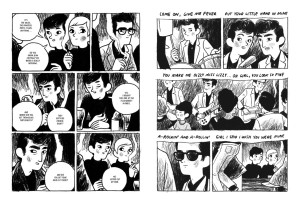

Baby’s in Black has elegantly textured lines and smoky, smudgy pictures that look striking and instantly appealing, beginning with Kirchherr’s ex-boyfriend hearing the Beatles playing in a cellar and excitedly convincing Astrid to see them. The design pulls you in, but Bellstorf’s carefully modulated drawing and the doll-like faces of his characters have a flattening effect on the drama of his narrative. It has the same even, calm and slightly distant feeling no matter what is happening. Whether this detachment is deliberate or not, it combines with the almost identical character faces to hold the story back. The design and textures of the artwork are beautifully minimal, the spareness based on tiny little differences. Almost everyone has the same face, with identical eye shapes, large round ears and petite button mouths. Slight variations in noses and hairstyles are all that separate the designs. John Lennon’s long nose, Sutcliffe’s glasses and Kirchherr’s extra-smoky eyelashes make them the only protagonists whom you can identify with a glance. This is a particular problem for the storytelling when Stuart stops wearing his glasses. When Astrid is alone with Klaus or Stuart, it takes several panels and some careful observation to work out which man is which.

Bellstorf’s way of effacing details applies to the structure of the story itself, with the most dramatic parts of the narrative happening off-panel. Everything is revealed in conversations and the reader is forced to fill in the gaps. There is a lot of information about the causes and effects of these events glossed over by this style of storytelling, perhaps attempting to take a story that readers who are Beatles fans will already know very well, and give it a different twist.

For readers who don’t know this story intimately, that information can be found in a text piece by Jon Savage at the end of the book. This extract from a essay about Kirchherr fills in the details of the relationship between her, Klaus Voormann and the Beatles. If you are unfamiliar with their history it will be helpful to read this and then go back to tackle the main narrative again.