Review by Fiona Jerome

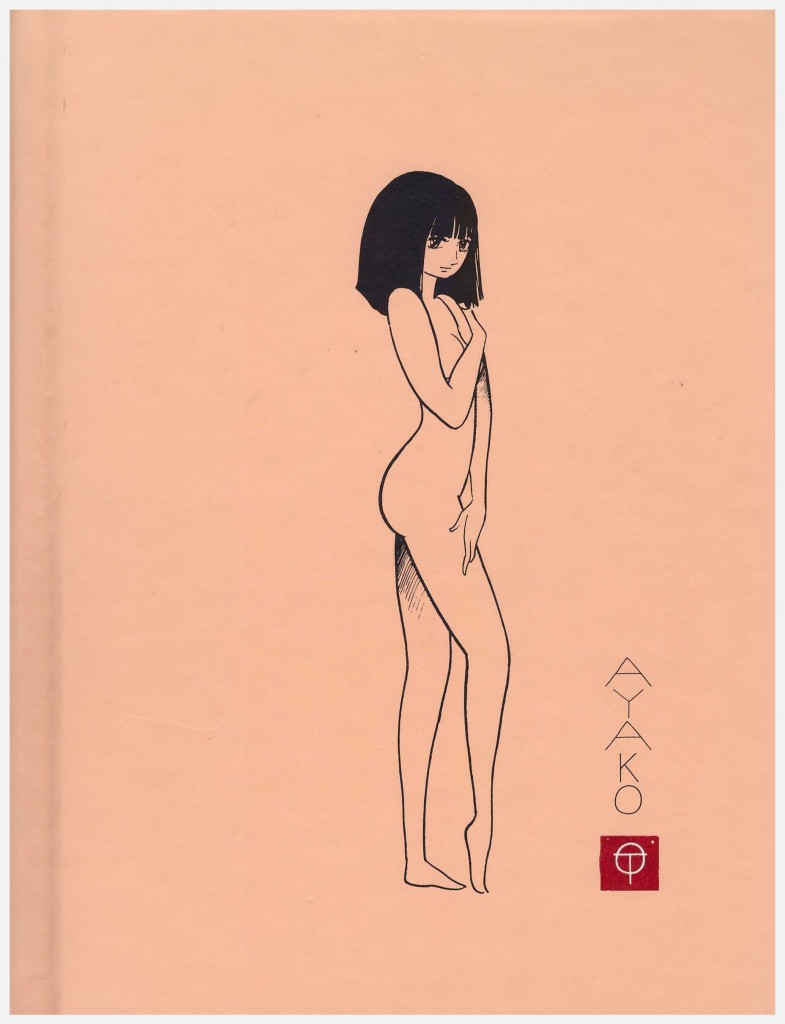

Osamu Tezuka, considered the godfather of manga, produced a massive, wide-ranging body of work, including Ayako, an intriguing family saga set in post-World War II Japan, which he created in 1972-73. Originally serialized in Big Comic, this edition brings together the three original Japanese volumes and offers the reader Tezuka’s interpretation of Japanese history during the country’s reconstruction between the late 1940s and early 1970s.

He does this by following the fortunes of the Tenge family, local lords, for 400 years looked up to by the surrounding countryside; the post-war world threatens them on all sides, from having large parts of their land given to farmers who were once their feudal tenants, to the shame of having Jiro, the family’s second son, return from an American PoW camp, rather than having the decency to die. However we soon discover that their much-lauded family honour is an excuse; greed and jealousy are their real motives. When Jiro returns to his rural home he discovers that his little sister Ayako is the result of his father sleeping with eldest son’s young wife in return for signing over the estate to him.

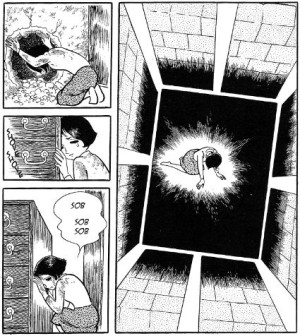

Later in his life Jiro declares that on his return he became the dumping ground for all the family’s sins. Ayako witnesses him washing blood from his clothes, so to silence her the family gather and vote to lock her in the cellar, telling investigating police that she has died. Some pretend it’s only a short-term measure, but at heart they know what is really going to happen. Ayako spends twenty years in the cellar while the world moves on over her head. She’s naïve, ignorant of social interaction and unable to differentiate between love and sex.

Throughout the story Tezuka uses the child-like Ayako both as a symbol for Japan and as a contrast with the increasingly debeased behaviour of the country, represented by the rapid corruption of her brothers. Ayako is often compared to the work of Zola, for its unblinkered and unblinking examination of human nature, and its sudden and often unlikely, symbolic turns of event. Tezuka also has Thackery’s gift for painting grotesques and then showing how they are not completely irredeemable, and for showing how the seemingly innocent are guilty of sins of omission, hesitation and weakness.

Displaying Tezuka’s familiar combination of fluid, simple figure drawing and detailed backgrounds, Ayako shows Tezuka’s mastery of expression and particularly of line weight when drawing. He manages to draw his elegant heroine naked without a hint of salaciousness, then switches to dynamic, almost roughly inked violence in moments. Sometimes the pacing does jar, with major events dealt with in a page or two, and sometimes a single facial expression is left to tell a huge chunk of the story, using pacing to reflect how much or little particular events mean to the characters.

Although pacing and sudden plot developments may at times seem odd, overall this is a prime piece of work, all the better for being tightly contained, full of finely drawn characters and some beautiful page design.