Review by Roy Boyd

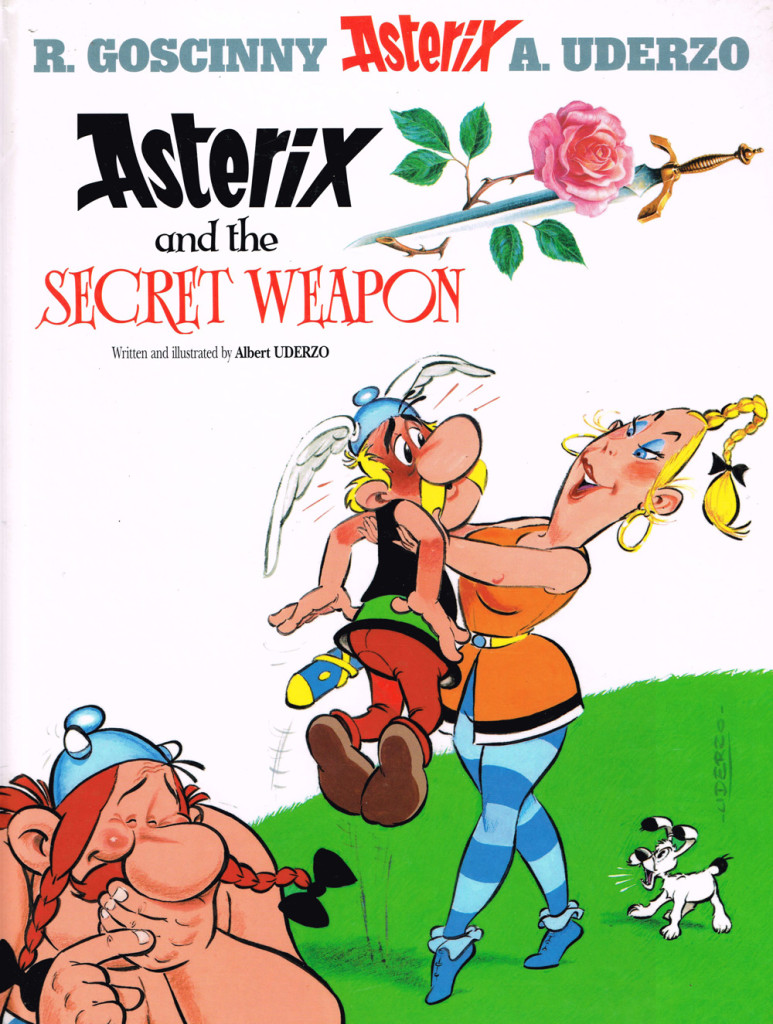

Asterix and the Secret Weapon, the 29th book in the series, is the fifth to be written and illustrated by Albert Uderzo. A female bard has been hired to replace Cacofonix, who takes himself off to live in the forest in a huff. The lady in question, Bravura, is soon butting heads with many of the village’s men, including Chief Vitalstatistix, who leaves to join Cacofonix in the forest. Asterix is next to disagree with the abrasive bard, and is so angered by her actions that he punches her! For the crime of striking a woman, he’s exiled, and then Getafix gets into it with Bravura. He’s exiled too, and, in a show of solidarity, they’re joined by every man in the village. They head off to the forest and soon, without any women around, seem to be having a high old time of it, drinking and eating wild boar.

Of course, this wouldn’t be an Asterix story if there wasn’t some other complication, in this instance the Romans and their secret weapon: a troop of female legionaries. Caesar is aware that Gaulish gallantry won’t allow them to strike women, which, of course, ties into events that have been playing out in the village. Discovering the plan, Asterix and Bravura put aside their differences and hatch a scheme to defeat the leggy legionaries.

One realises immediately that this book is going to tackle to subject of feminism, though any hope that Uderzo is trying to make amends for their portrayal of women in many previous stories is quickly shattered, with Uderzo instead poking fun at the women’s liberation movement. While other books have a degree of sexism as a by-product of the type of stories they tell, this one tackles the subject head-on, with about as much subtlety as Asterix and Obelix normally bring to bear on most matters (that is, none). His characters’ final plan to counter the threat of the female legionaries (with the exception of their hefty leader, all beauties that wouldn’t look out of place in Miss World) is jaw-dropping in its sexism, with his conclusion about what is really important to women sure to upset some modern readers.

Uderzo, not surprisingly, never writes as well as his long-time collaborator, writer René Goscinny, though his writing had certainly improved from his early solo efforts.

It’s odd that Uderzo would choose one of the most clumsily drawn panels from the book to feature on the front cover. This may well be the worst cover of any Asterix book, with the little Gaul looking strange, fat-arsed and inelegantly posed. Bravura also looks very odd, though she at least looks odd throughout the whole book. She was apparently based on a real person, but Uderzo would never admit who she was. which was probably kindest, as she really is a strange looking and unattractive character. On the whole, though, the book looks good, if not quite as detailed as some of the earlier adventures.

So, if you can get over the sexist handling of the subject matter, there’s all the usual elements that you’d expect from an Asterix book, with Uderzo maintaining the tradition of shamelessly recycling gags and situations. Not as good as many earlier adventures, but not a bad addition to a superb series.