Review by Ian Keogh

Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None is claimed to be the best selling mystery novel of all time since its 1939 publication, although the vast majority of those sales were under the previous offensive title. Remarkably that was still used for this graphic novel’s French edition in 2002. It’s Christie at the peak of her plotting ingenuity, as much intellectual exercise as novel, so much so that two postscripts are required to the main event.

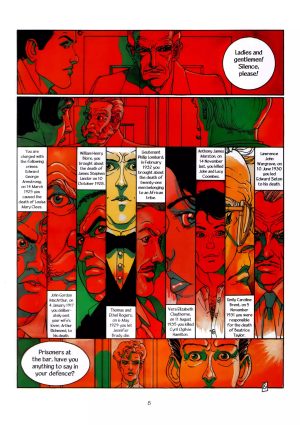

François Rivière’s adaptation begins by introducing eight people who’ve received an unexpected invitation to a holiday on the remotely located Soldier Island off the English coast. They don’t know each other, and they come from all walks of life, one of them named General MacArthur, amusing with historical perspective. In their room, each finds a plaque featuring a nonsense rhyme about multiple deaths, the title of that changed here to Ten Little Soldier Boys, each of which is murdered. It subsequently turns out there is a connection between the guests, as each has escaped punishment for murder, an accusation also levelled at the recently hired butler and cook.

These are listed on Frank Leclercq’s sample art, also showing his talent for designing a varied cast and an unorthodox fondness for exceptionally vivid colour. It’s a constant distraction from what’s otherwise subtle storytelling.

As the guests discuss the alleged crimes, each claims there were mitigating factors, although as we later share their personal reflections we learn some deaths involved a degree of culpability. Still, the mystery remains about who might know about such different circumstances in different places over a period of ten years, and who’s removing a model soldier from the dining room display every time a guest dies.

There’s a simple reason And Then There Were None has proved an enduring bestseller, and that’s because it’s a cracking story retaining its secrets until the end. Readers follow the ebb and flow of suspicions between the cast as they discuss matters, realising early that one of them must be the killer. The two audacious postscripts are well transferred by Rivière. During the first others fail to piece the circumstances together in hindsight, while the second is an ingeniously concealed confession revealing all.

This isn’t necessarily the best way to read a genuinely chilling mystery, but Rivière contracts the story to fit a limited page count without making it seem as if anything is lacking. It results in a high standard that few other graphic novels in the series attained.