Review by Frank Plowright

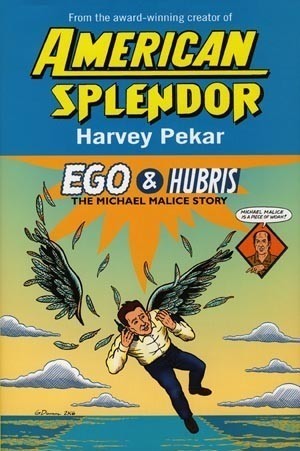

A union of Harvey Pekar with the Vertigo imprint, best known for horror and crime series, is at face value extremely strange. Consider it from Pekar’s viewpoint, though. As acclaimed as American Splendor had been, it was never a major moneyspinner, and Pekar had always been limited to using the artists he could afford, cajole or coerce into drawing his material. His alignment with Vertigo may have been an uneasy fit, but it extensively broadened the quality of artists available to him. Would Pekar have commissioned Leonardo Manco or Glenn Fabry when self-publishing?

Other better known artists drawing their first Pekar strip include Richard Corben, Hunt Emerson, Gilbert Hernandez and Chris Weston. It’s Corben who surprises the most, with the topic at hand (a search for his daughter’s lost glasses amid the autumn leaves) being so far removed from his usual material. A good artist is a good artist, though, and Corben’s illustrations of Pekar shuffling despondently down the street expecting to shell out for replacement specs are exactly what’s needed. Chris Samnee, then not so well known despite his excellent Capote in Kansas, also greatly impresses with a story about Pekar having to pick up his daughter during a snowstorm.

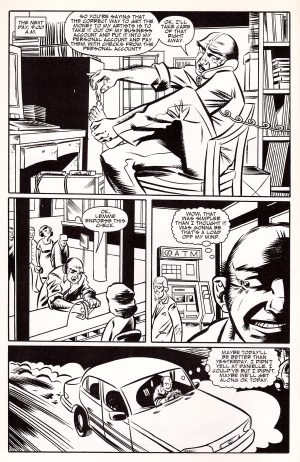

The artists that generally work best on the observational material, though, are those who’ve been working with Pekar a while, such as Dean Haspiel (sample art), who contributes the most strips here, Ty Templeton and Josh Neufeld. Their characterisations of him hit the right tone between the grouch, the man who takes pleasure in the small things of life, and the worrier.

With the arrival of foster daughter Danielle, Pekar’s material experienced a notable shift of emphasis. Parenting has diminished his opportunities for self-reflection and transferred many of his concerns, but it’s hardly exhausted the needless worry he puts himself through. He tends to think ahead, and a perpetual anxiety is that his books will lose popularity with the consequent drop in income. He’s aware of his compulsive nature, and it feeds his best material. “Am I really so weird, or are there a lot more weird people out there who just won’t admit it?” he asks after neurotically agonising over a broken phone connection.

For all his reputation as a curmudgeon, not unfounded, there’s a broad streak of self-deprecation splicing Pekar’s choice of subject. The Fabry illustration concerns a researcher from the Oprah Winfrey Show calling him up on the basis that he can complain on any subject. Fabry perfectly captures Pekar’s expression of bemused incredulity.

It’s interesting to note the overall strength of this material, indicating that despite his combative nature and a strip delivering passing thoughts on editors, editorial input played a part.

Having already published The Quitter through Vertigo, this must have been a successful arrangement, and a second collection followed in 2009, Another Dollar.