Review by Ian Keogh

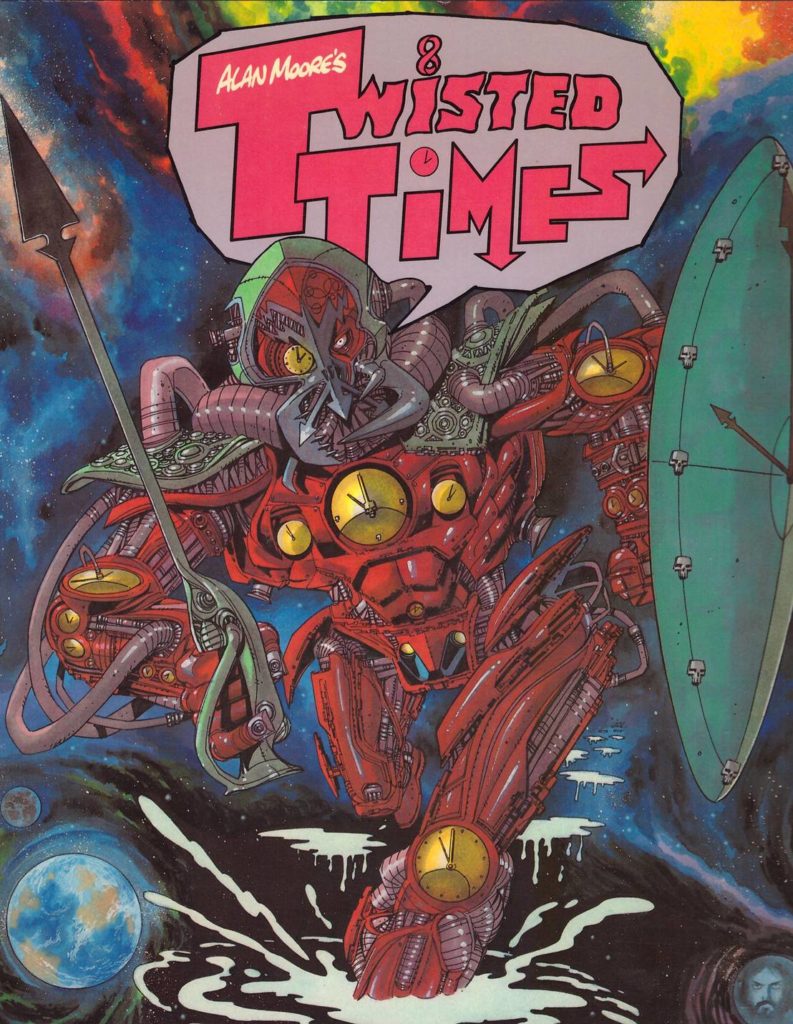

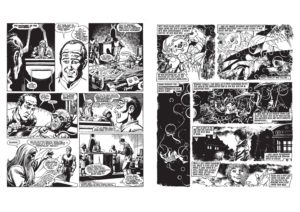

Twisted Times is a companion volume to Shocking Futures, both compiling the short stories Alan Moore wrote for 2000AD filler features in the early 1980s. It’s slightly different in conception for half the content being a series that never was, the absurdist misadventures of Abelard Snazz, the man with the double decker brain. Unlike most 2000AD one-offs, these four stories each stretch across eight pages, allowing Moore double the space to extend his own creative brain. Snazz considers himself a genius, but woe betide those buying into that idea. The conceit is that Snazz over-thinks a problem, and the joke is that when a new problem is created, Snazz then makes it worse, exemplified in robot police going too far, and Snazz’s solution being to occupy them with robot criminals. His visual appearance is memorably unsettling, especially when drawn by veteran artist Mike White (sample art left), and it was Moore seeing something similar in book of optical illusions that prompted the character’s creation.

One narrative has it that Moore single handedly elevated the quality of comics writing. There’s some truth to that, but it was by virtue of his applying thought when too many others didn’t in the early 1980s. It’s certainly what made his short stories for 2000AD stand out, revealed by seeing them in the context of what others produced in The Complete Future Shocks. While essentially trivial, the Abelard Snazz stories are elevated by the jokes Moore packs in, visual and verbal, asides and up front, constructing a density.

The second half of Twisted Times is Moore’s selection of five strips he felt succeeded in fulfilling the brief of novel stories constructed around the notion of time. Two are collaborations with Dave Gibbons, ‘Chronocops’ being Moore’s favourite when he wrote the introduction. It combines a deadpan Mickey Spillane style narrative with ever more complicated and ludicrous time paradoxes as a pair of cops attempt to prevent time being altered. It’s still funny, Gibbons supplies a memorably emotionless Joe, and having to draw the same scene repeatedly with minor additions would serve him well on a later collaboration with Moore. ‘The Disturbed Digestions of Doctor Dibworthy’ is a simpler and lesser tale, although again requires Gibbons to draw the same character multiple times.

Moore collaborates with several mainstays of British comics whose very traditional approach was out of place in 2000AD, but the craftsmanship of Eric Bradbury and White is apparent, and it’s White who illustrates the most memorable story. Moore’s introductory comments about ‘The Reversible Man’ note the idea was waiting for someone to trip over it, perhaps in a collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald short stories. It’s what he does with the idea of someone living their life backwards that resonates, a normal life given poignancy simply by reversing it. Jesus Redondo’s methods are trippier, used to good effect on two darker stories, both using a first person narrative to engage. A succession of terms referring to time are employed in showing how time works, more trivial, but Bradbury’s art ideally suited to the notion of timelessness.

What may be preferable to this and Shocking Futures is The Complete Alan Moore Future Shocks. Actually it isn’t, as Moore’s selection process here weeded out stories he knew were weaker.