Review by Graham Johnstone

Starting with Jack the Ripper, Rick Geary develops his Treasury of Victorian Murder concept into a series of book length case studies, having tested the water with an earlier volume, which set the scene of the Victorian era, and looked briefly at three cases.

The choice of the first full length subject was not such a no-brainer as it might seem as Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell ‘s take on the story in From Hell was already being serialised to critical acclaim. The two books though are very different: Moore takes the murders as the starting point for a fictional exploration of Victorian society, while Geary assertively sticks to the evidence, and resists the urge to speculate.

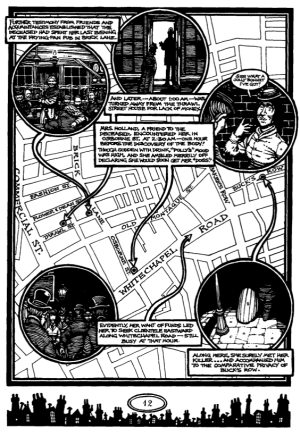

The book is presented as “Compiled from the journals of an unknown British… armchair detective”. This is no omniscient narrator, seeing what actually happened in those dark alleys and locked rooms. This (presumably fictional) gentleman, like Geary himself, simply explores the evidence and theories as they emerge. This is no easy task, as he demonstrates with multiple witness statements on a single incident never quite adding up to a coherent account.

Geary’s approach to this whole series could be described as ‘forensic’. That’s evident from the third page, presenting the results of a post-mortem: “The wounds were inflicted left-to-right, leading the doctor to further surmise that the murderer is left handed…” The tone is always matter-of-fact – more like a court report than one of the era’s salacious Penny Dreadfuls. He seems almost less interested in the murders themselves, than in the remaining mystery, and the process of detection, resulting in a critical questioning of what, from all this circumstantial evidence, is truly known.

In these sixty small pages, we follow the case over almost a year. Geary’s near invisible skill in these volumes is in the distillation and organisation of the massive amount of ‘information’ available. Yet there’s an exacting clarity about, say, the parts played by different investigators and medical experts. We see City and Metropolitan officers arguing over the significance of graffiti near the crime scene. It could also be a provocation to hate crime, yet the Metropolitan Commissioner puts an end to debate “in an inexcusable breach of investigative procedure” by wiping it off the wall himself.

Geary, like Moore, looks into the background of the victims: the grinding poverty, relationship breakdown, and often alcoholism that drove these women to work on the streets. They carry on even at the height of the murders. There’s a poignant moment when we see Polly Nichols’ estranged husband confronted with her remains: “I forgive you for everything, now that I see you like this.”

The visuals are similarly understated with no naked corpses or gaping wounds. Geary’s quirky stylisations also offset the heaviness of the material. When the text refers to earlier murders, with 39 stab-wounds to one woman and mutilation of another, he draws street scenes with mounds of cloth half hidden in doorways, only hinting at the prone figures beneath, and merging into splashes of black ink. Realistic depictions would be unnecessary, even gratuitous, and uncomfortably pushy of the readers’ response.

The inking here is slightly heavier than usual for Geary, giving a dark, gothic look, with white lines on black evoking period woodcuts. He’d tone down this effect for the later books, although none of those stories were as gothic in nature as this.

Jack the Ripper is equal parts gripping story, illuminating documentary and graphic narrative masterclass. It was later combined with subsequent investigations The Fatal Bullet and The Beast of Chicago as the first Treasury of Victorian Murder Compendium.