Review by Graham Johnstone

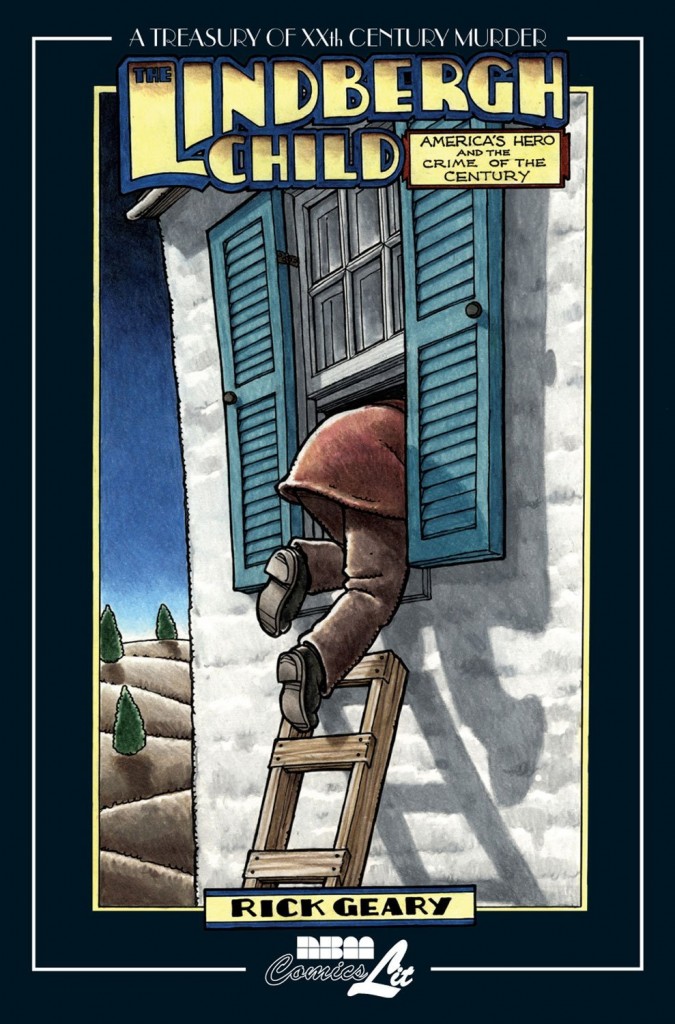

Having already completed eight volumes of his Treasury of Victorian Murder, Rick Geary moved onto the 20th Century, beginning with the famous case of the Lindbergh baby. He adopts the same charming drawing style with an analytical approach, and an almost forensic rendering of the investigation.

Colonel Charles Lindbergh was famous for his pioneering non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. Less well known was that his young wife also accompanied him on his flights, and they set a joint transatlantic speed record. They were quite the celebrity couple of their day. Young, beautiful, heroic, and affluent, they built a large house on acres of land in the scenic New Jersey countryside. When their baby was born they must have seemed to have it all.

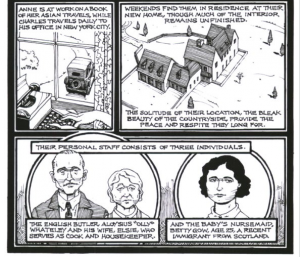

The book begins with Geary’s usual (for this series) map of locations for key events. The aerial perspective view of the house centred on the entry point (means of access shown in place) is typical of Geary’s diagrammatic clarity. Note that these maps give locations for some of what follows, so effectively contain spoilers.

After a short introductory chapter Geary provides a day by day account of key events. Following the initial crime of Charles Jr’s abduction, various people come forward to act as intermediaries with the extortionists, which muddies the waters for Lindbergh and those helping him. There are multiple strands to the case, some of which prove loose ends. These are always introduced in a neutral fashion, and we follow each avenue of enquiry as if part of the investigation team, trying to retain and make sense of all these strands. Geary provides admirable clarity that puts us into the case. There are secondary victims, a staff member with weak and shifting alibis who cracks under the pressure, and is exonerated too late; a wealthy philanthropist, led on a costly wild goose chase by an opportunist.

The book is fascinating as a view of developing crime-detection methods. Experts are called in to find fingerprints, and analyse an implement left at the crime scene. A psychologist prepares a profile of the unknown criminal. A wood expert identifies that the wood came from a specific lumber yard, except for a single piece: it is thought that the maker has run out and taken a piece from some item to hand. A classic Geary image shows how part of this implement matches up to a missing floorboard in a suspect’s attic. “The wood-grain and nail holes line up precisely”.

The art style is by now typical Geary, with his practiced slightly wonky drawing. His inking is like a update on old engravings: he creates tones with tidy hatching, that models forms into an almost sculptural, three-dimensional effect. There are a lot of characters, yet Geary saves this being repetitive, by capturing them in mock period photographs, blending realism with just the right amount of caricature to make them distinctive.

There’s a lot of work and skill in turning this mass of information into a coherent book, indeed the page-turner it is. Each of the mere eighty pages is a coherent unit of information, well designed, appealing, with a variety of panels and inset details.

Geary is by now playing to his strengths here, nonetheless it’s another fascinating story, flawlessly delivered. It’s also a great place to start for anyone new to graphic non-fiction, or simply graphic novels.