Review by Ian Keogh

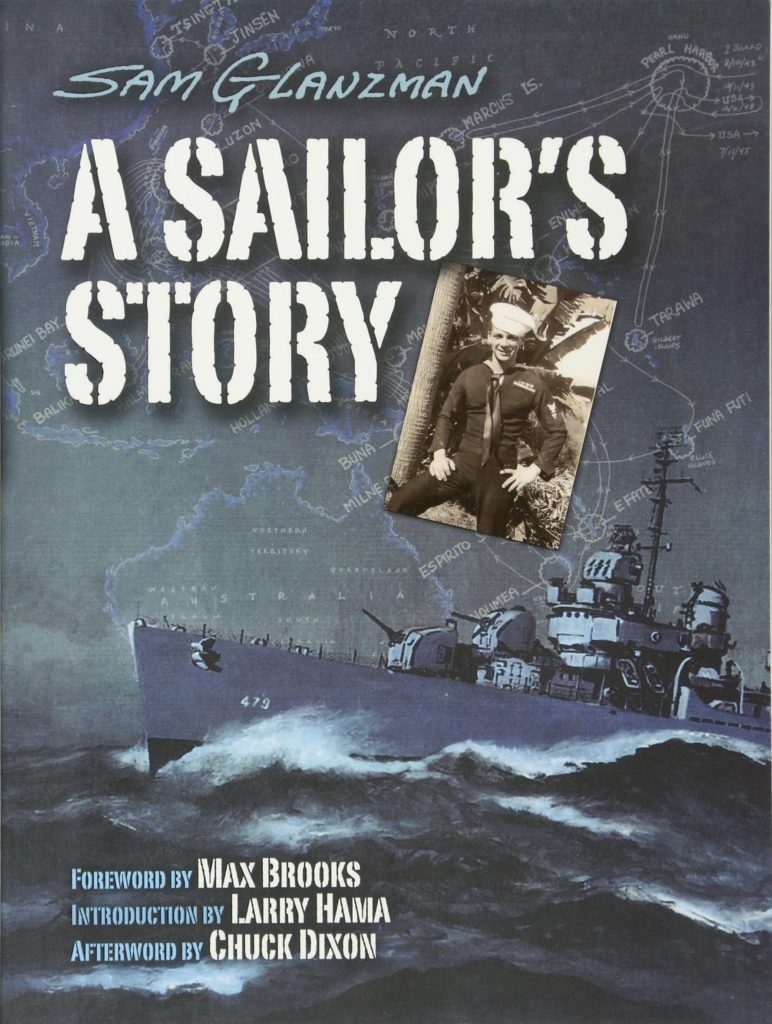

Possibly more so than any other comic creator, Sam Glanzman’s World War II experiences had a profound effect on his comics work as well as his life. He signed up for the navy at eighteen, and was assigned to the U.S.S. Stevens in 1943. Throughout the 1970s he contributed touching and partially fictionalised anecdotes about the people he served with and met to DC’s war comics, sometimes funny and sometimes tragic and now collected as U.S.S. Stevens. In 1986 Marvel’s graphic novel line gave him the opportunity to produce two more direct volumes of memoirs humbly titled A Sailor’s Story.

The result is a mixed bag. It’s honest, modest and heartfelt, yet for long sections little more than descriptions of routine, which are meticulously recalled without being captivating. With one exception, Glanzman decided not to repeat the anecdotes he’d already used in the anthology stories, and over the first book in particular, the well seems to have run dry. This is further compromised by Glanzman noting that the violence and death of combat is horrifying, so he wouldn’t be showing it. That’s understandable given his personal involvement and good friends lost, but it also removes the action from a war memoir. He relaxes that view for the second book, and it’s far more effective in conveying the horror of a naval attack, without ever glorifying it.

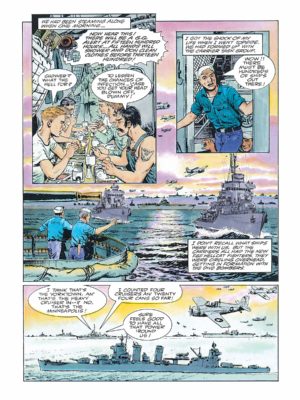

An impressive list of fellow creators provide testimonials as to Glanzman’s work and personality, with his Marvel editor Larry Hama writing a loving introduction. A naturalism and solidity reinforces the authenticity of Glazman’s art, with an absolute precision about the reproductions of a destroyer’s inner workings, sometimes with annotated diagrams, but many panels featuring people have a depth problem giving a two dimensional look. More shading could have avoided this. He’s on happier ground with longshots of the U.S.S. Stevens and the actual missions during the course of the second book, originally published with subtitle of Winds, Dreams and Dragons. The opening pages of Japanese air attacks surely nail the sensitivity Glanzman was aiming for while showing the horrible human cost.

There’s a considerable contrast between the two main stories, with the second being better despite a scrapbook feel. It’s more personal and there’s an intimacy as Glanzman moves away from structured routine into how he and his colleagues felt, and how they passed the time, with Glanzman disclosing more. The art is also different, featuring more views from distance and more combat sequences, all tied into reproductions of the ship’s daily log over 1944 and 1945, the locations providing memories of incidents.

What’s promoted as a new U.S.S. Stevens strip is new in the sense that it wasn’t previously published, but it dates from Glanzman’s contributions to Marvel’s magazine anthologies in the 1980s. As such there’s an artistic consistency with the remaining material.

The included testimonials alone show A Sailor’s Story is held in higher regard than this review would suggest, Glanzman’s work ethic and honesty resonating greatly with a select band of professionals. That appreciation never progressed beyond that recognition is surely a source of puzzlement and frustration, and it’s partly thanks to their efforts that this collection exists.