Review by Frank Plowright

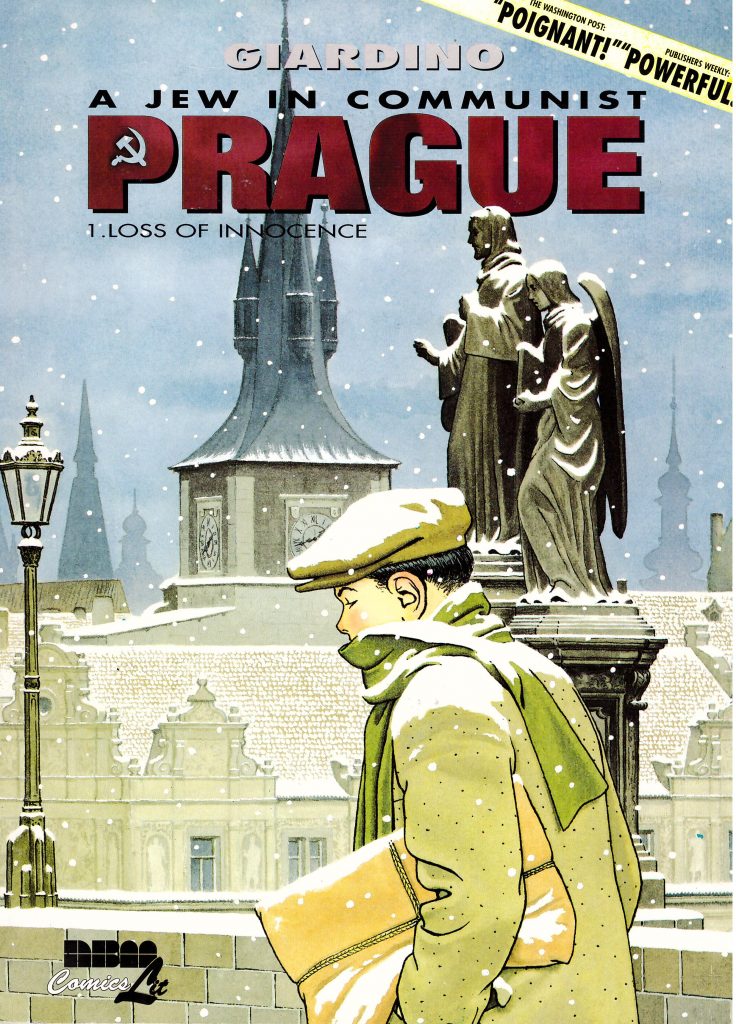

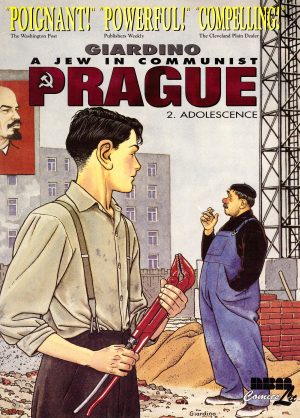

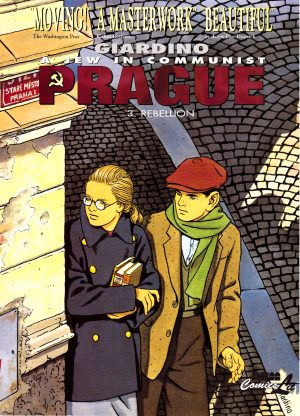

He began his graphic novel trilogy in 1994, five years after the Soviet hold on what was then Czechoslovakia had been dismantled, but Vittorio Giardino set it in the 1950s when that hold was an iron grip. Stalin still lived, his murderous ideology filtering through to all the communist satellite states, and among that was a streak of anti-semtism.

Life changes in an instant for Jonas Finkel at thirteen when his father is arrested for unknown crimes. Such is the suspicion, paranoia and fear among Czech citizens that he and his mother are ostracised. Anti-semitism soon raises its head, along with an envy of supposed privilege and a presumption that Professor Finkel has to be guilty of something or he wouldn’t have been arrested. Jonas is prevented from continuing his schooling on the basis that the state cannot afford to educate everyone and he’s grown up in a house with books. Meanwhile Edith Finkel is followed, spurned and targeted for attempting to discover why her husband has been arrested. Giardino shows how all logic begins with the infallibility of the state, and to suggest otherwise is disloyal, which has its own consequences. An assortment of obstructive minor officials collude in what amounts to persecution as the family circumstances become ever more distressing.

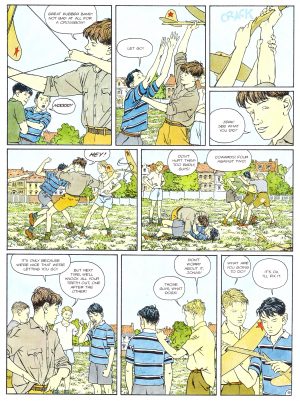

A Jew in Communist Prague is, however, more than just a condemnation of the times, which could become one-note. By hanging the story around Jonas at his age, Giardino ensures a second viewpoint. Edith at least has an understanding in principle of what’s happening, lacking in Jonas, so he attempts to continue his life as normal while continually confronting new obstacles. Friends are shed, and he has the natural inclinations of the young heterosexual teenager, which play out unfortunately. His lack of comprehension and stoic acceptance work well in accentuating reader sympathy.

Giardino is a stunningly precise artist. Almost every panel is a beautifully composed and detailed individual scene, but not at the cost of progressing the story. Every person featured is individually created, with differing facial and bodily characteristics, a technique taken for granted in European material, but rare in English language comics. Giardino’s one artistic weakness is that the precision of his line occasionally works against the high emotional content, which can come across as staged.

When first translated in 1997 Giardino’s mixture of naturalistic story with heartfelt angry condemnation of an appalling social system was practically unique for English language material. This is no longer the case, but far from being sucked down by what’s followed, Giardino’s subtlety, attention to detail and fantastic art remains exemplary. The story continues in Adolescence.