Review by Bill Stone

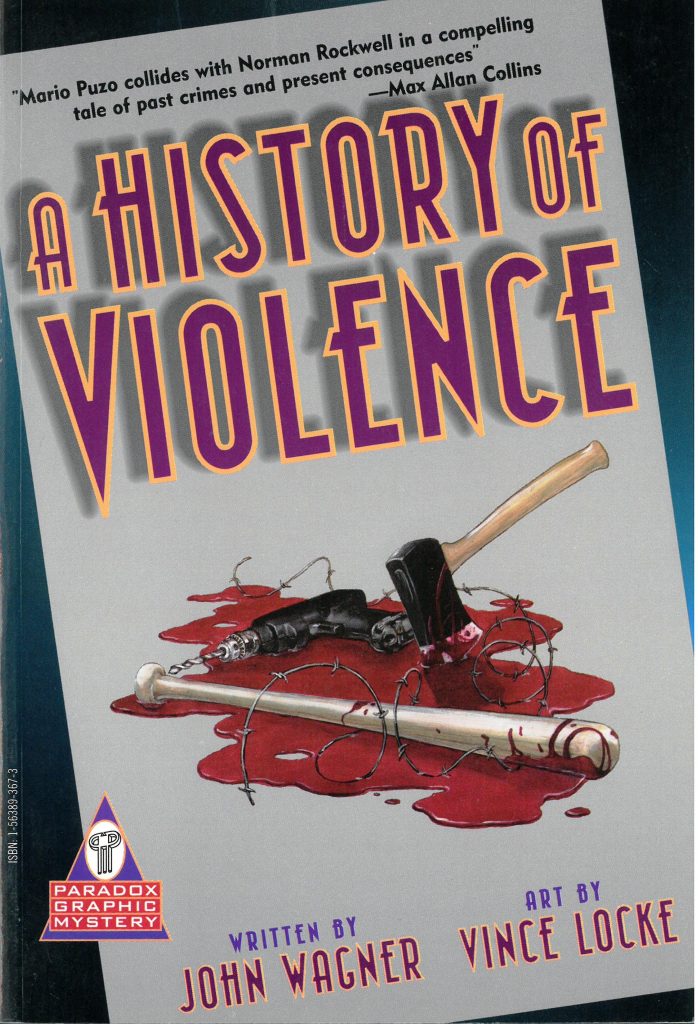

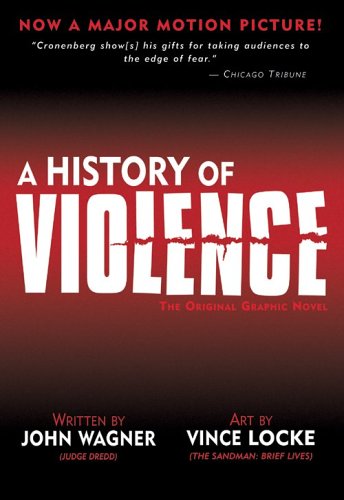

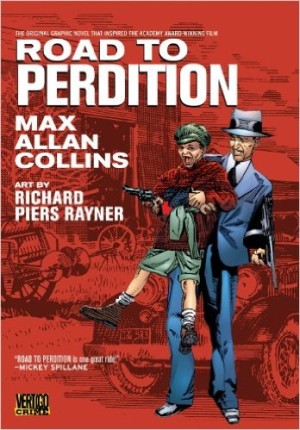

John Wagner’s A History of Violence has had an impact beyond its 286 pages of black and white line images might give you cause to believe. Eight years after it was published, David Cronenberg used it as the basis of the film of the same name upon starring Viggo Mortensen and William Hurt. The theme follows a well trodden path in that violence and crime have unforeseen consequences that echo catastrophically down the years, no matter how noble the reasons behind it.

Tom McKenna runs a diner in small town America and is the archetypal ‘peaceful Percy’ agreeing to play softball at the forthcoming barbecue before his life starts to fall to pieces around him. Two murderous villains attempt to rob and murder Tom who manages to turn the tables on them with seemingly little effort or thought. As news of his derring-do spreads via the media, Tom’s past begins to reassert itself, his life spirals out of control and the body count begins to creep inexorably upwards.

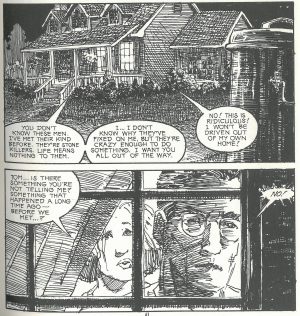

Vince Locke’s art is effective without straying far from the minimum needed to illustrate the story. At times the more delicate reader will be relieved by this, as there are extremely violent passages and having some horrors alluded to rather than precisely delineated is a blessed relief. While there are panels with barely any ink, overall his tone reflects the moral murkiness of the piece and darkness predominates.

The plot is well constructed, fits neatly together and doesn’t take any missteps until the last few pages tie matters up rather too neatly. This is emblematic of a weakness running though the story in that elements that you might expect to take up a sizeable amount of time and space to resolve are addressed and resolved in double quick time. Tom’s wife reacts more kindly than many a wife would on learning her husband has been deceiving her since day one, and within a few panels is a fully paid up member of Tom’s team. If only real life could be that simple.

The film doesn’t follow the book all that faithfully as the story progresses, and doesn’t allow as much time for the setting up of Tom’s past as the book does. But what it does do, that the source material here doesn’t, is explore the shifting sands of relationships and how they can be finally balanced. If you view this as purely a crime story exploring violence, revenge and their associated consequences, this may not matter that much. It barrels along efficiently and ticks off the requisite boxes. If you would hope for some acknowledgement that life can be grey rather than black or white, this can leave you wanting.