Review by Ian Keogh

Sadly, every generation has a tragic, tormented rock musician, and Kurt Cobain is the 1990s example. His brief and sad life has been extensively documented, making him a difficult biographical subject, at least if a biographer wants to avoid just rehashing the commonplace. Godspeed does that.

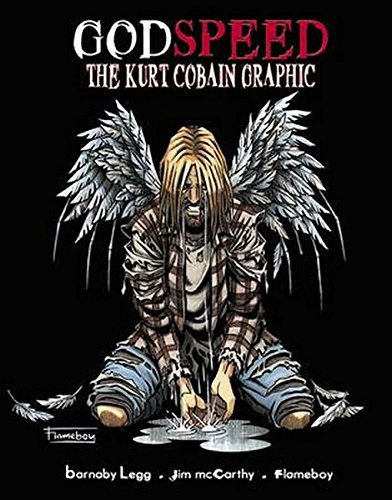

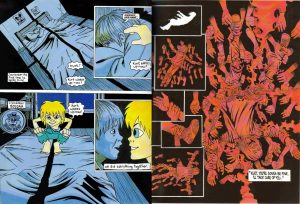

The cover may overplay the morose sentimentality, but the approach taken by co-writers Barnaby Legg and Brendan McCarthy is to weave Cobain’s life story into more fanciful realms, and it’s generally a method that works. An early example is the influence and comfort of imaginary childhood friend Boddah, introduced on the sample art.

In essence Cobain’s early life is sadly commonplace, featuring parental arguments, divorce, and his mother’s unsuitable choice of manipulative partners forming a frustrated and downbeat worldview. Like many others, the release of seeing a band whose music amplified his feelings was a transformative experience, in Cobain’s case the Melvins, but unlike many others he had the dedication and talent to inspire his own generation.

Flameboy, or Steve Beaumont as he’s known to his mates, is an illustrator rather than a comic artist, and tells Cobain’s story in a series of iconic representations rather than panel to panel continuity, although the constant brightness of the colours seems an odd choice for a dark life. He does have a nice line in juxtapositions, although that could be down to the script. Flameboy’s at his absolute best when there’s no story to be conveyed, just a mood, and time and again, as per the sample art he delivers a great statement. A haloed image is going too far, though. He’s good at supplying Cobain’s many moods and later wife Courtney Love, but isn’t as strong with the likenesses of Nirvana bandmates Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic.

Using a first person narrative is an interesting choice on McCarthy and Legg’s part. It enables the introduction of the unreliable narrator, refusing to acknowledge what all around him can see, but effectively conveys the demons constantly haunting Cobain and how his solutions set him on an inevitable path. Some obvious spelling errors speak to a lack of editing (“Gerry Garcia”, “Grim’s Fairy Tales”), but there is care taken to contextualise, especially via Peter Doggett’s five page introduction.

This has proved a perennial seller, with a second edition published in 2011, but why’s it Graphic not Graphic Novel? Anyone captivated by Cobain’s music is going to want Godspeed, and the finer qualities should ensure an audience beyond.