Review by Ian Keogh

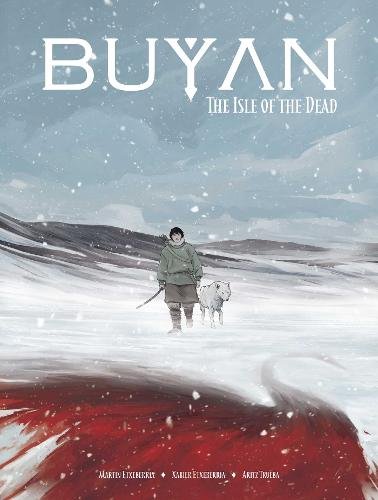

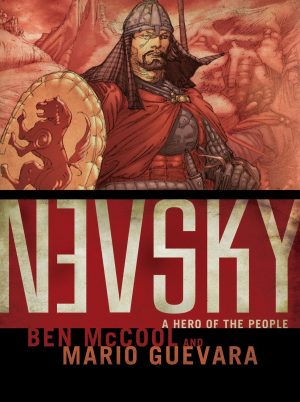

When casting about for historical Russian representatives of Soviet ideals in the mid-20th century, film maker Sergei Eisenstein built a myth around the little that was known of Alex Nevsky, a heroic 13th century prince who’d repelled a German (or Teutonic) attack. He features early in Buyan with Russia again under attack from the Teutons, and anticipating Batu Khan’s Golden Horde also have their eyes cast North once they’ve finished with Europe. That’s the political situation into which Maansi of the Nenet people wanders, walking South accompanied by his dog, anticipating his death in the legendary land of Buyan.

It’s a gloomy mood set by writers Martin and Xavier Etxeberria, and that’s sustained all the way through Buyan. 13th century times were hard, then you died. If you were lucky it was peacefully in bed, but few of those we meet are lucky. Before we’re introduced to him Maansi’s already met members of the Golden Horde, and Nevsky’s also familiar with them, his victory against the Teutons having come at a cost. For a long time the writers construct small dramas against the larger background, and spend so much time doing so that it’s difficult to determine an ultimate path.

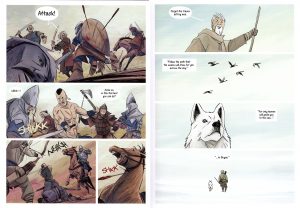

Reflecting the times, any glamour is absent from Artiz Trueba’s artwork. He’s an inconsistent artist learning on the job, sometimes capturing a rare reflective moment, yet often supplying awkward, angular figures. At their best these can charm, resembling old school 2D animation cels, and at their worst the people are poorly proportioned with occasional foreshortening not working. The main problems are ironed out by the halfway stage, but overall it’s not the type of awe-inspiring art usually given the oversized, hardcover treatment.

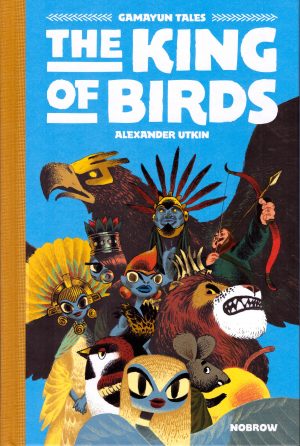

In addition to the political background, there’s an exploration of Russian and Slavic myths in lands where Christianity had relatively freshly been enforced. The research has been carried out, but the fantasy intrusion of legends is haphazard, and as there’s no indication Buyan is to be continued, the story plays out that way also. Given what occurs, so much space is taken up featuring people and events that don’t matter and whose presence could have been replaced by a caption or two. An example is Nevsky, so prominent at the start, yet almost without purpose (and “Prince” is twice lettered as “Price” when he’s first mentioned). It’s only in the final twenty pages of around 200 that Buyan springs some real surprises, previously well concealed, but they can’t make up for the ramble that preceded them.