Review by Karl Verhoven

Walter is middle-aged and still lives with his mother in a grumpy relationship of convenience, two trapped people, neither happy. When he discovers his mother lying on the floor of his shed possibly having a heart attack, he won’t call an ambulance when she asks. “We’re not having any doctors in here!”, he responds, “The place is far too dirty”. Fearsomely intelligent, he’s also a bodger, constantly modifying the house to incorporate another time saving device, and fitting a counting device in his clothes drawer enabling him to discover if his mother has been prying.

Walter’s younger brother Roger has alcohol problems, and visits his mother weekly, but it’s some while before Willy Linthout introduces the younger brother to both, Charles, seemingly the most grounded of three brothers until we learn his son has recently committed suicide.

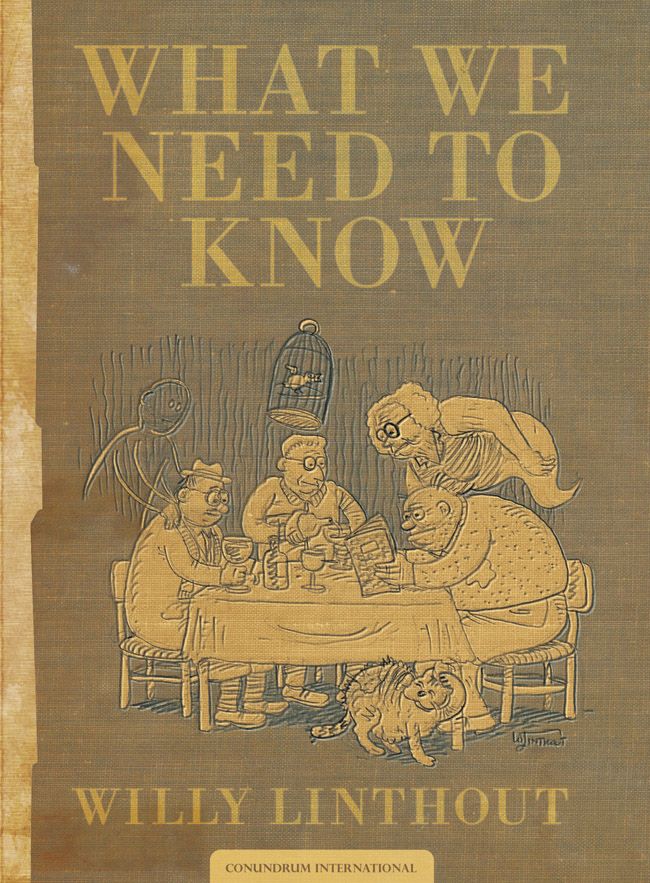

In isolation, What We Need to Know is a dispassionate and sometimes inappropriately funny look at a dysfunctional family not coping, with Linthout employing the comedy cartooning skills on which he’s built his career. Artistically it’s a virtuoso at work, but it’s problematical because at heart he’s addressing serious problems, yet the treatment seems to trivialise neglect, alcoholism, and being on the autistic spectrum. Before the penny drops about Walter’s condition he appears to be the comedy eccentric of TV sitcoms, deriving laughs from pratfalls and being a few degrees out of alignment with reality. We’re laughing at his jaw-dropping antics.

Linthout introduced Charles in Years of the Elephant as his own stand-in, coping with the effects of his son committing suicide. That could be seen as an entirely separate work, having lighter moments, but without Linthout falling back on comedy standbys, yet he makes deliberate connections. The most obvious is also drawing this entirely in pencil with no preparation lines erased, previously representing Charles’ confusion and disintegration, here the chaos exemplified differently by each brother. Visual devices associated with Charles are repeated, making little sense here in isolation (the chasm in the floor, the ghostly outline of his son). The positive aspect is the offering of some closure for Charles absent from the previous book.

It’s to be hoped the brothers Linthout’s introduced are fictional, as were Walter real it’s difficult to see how he’d have any contact with Linthout after What We Need to Know. He’s shown as a man without filter, entirely unaware of how he looks to others wiping his hands with his mother’s underpants after fixing a bicycle puncture, then eating a can of sardines with his fingers, still sitting by the roadside. Walter’s gradual disintegration becomes the predominant theme, and the dual meaning of the title gradually drops into place. To begin with it refers to a book in which Mrs Germonprez records recipes and other practical tips, something we later come to realise she’s doing for Walter’s future needs. The cover to What We Need to Know is cleverly stained to resemble something Walter’s frequently handled, but it’s a joke that will bypass casual browsers, who’ll just see a messy looking cover.

Perhaps without the comedy moments What We Need to Know would be too depressing, but it’s not what it first appears to be. Is it ultimately a story of state neglect and failure or the personal blind eye? Linthout suggests neither and offers no comfort, and because of that this will rattle around in your head long after reading.