Review by Frank Plowright

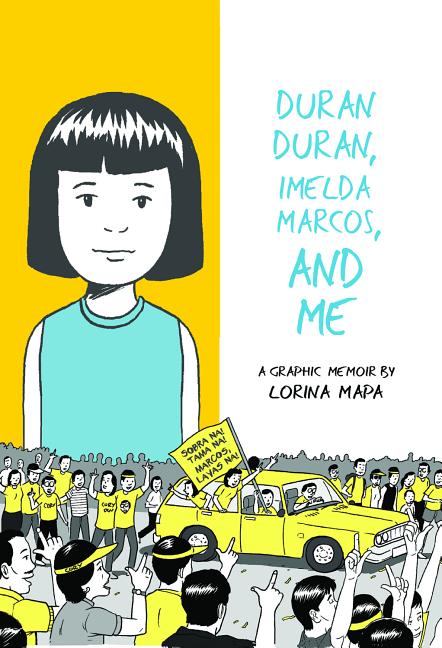

Lorina Mapa begins her memoir of growing up in the Philippines during the 1980s with a moment of great sadness. Now living in Canada, she learns of her father’s death in a car accident, and returning to Manila for his funeral prompts memories of her youth. She switches between past and the present of 2005 in what’s simultaneously a love letter to her family, especially her father, and a glimpse into another world and era for the English language audience. Mapa is a charming host with a strong memory for detail, yet able to avoid becoming bogged down in irrelevance.

Mapa’s drawing isn’t too far distanced from Scott McCloud’s cartooning, with a similar joyous expression to it. Hergé is another influence, acknowledged in passing, and like his work she keeps things simple, but it’s an adaptable style, effective for sadness and joy. Earning her living as an illustrator provides a head start, but Mapa has transferred to the demands of comics effortlessly, one example being the sophistication of her segues from past to present.

As with any look at another society and time, some aspects are astonishing, some taken for granted by Mapa herself, just mentioning as a matter of fact that her daily journey on the school bus was two hours in each direction. Being a citizen of two countries she’s aware of what will seem amazing, funny or unusual, combined with an innate talent for presenting the wistful or heartfelt moment. The family history is fascinating and littered with Filipino notables. Go back three generations from Grandmother Loreto and Mapa’s was an extremely wealthy family of sugar planters, their ancestral home now a museum. Dividing wealth among many children and Loreto’s dispersal of her own fortune between her brothers and sisters in gratitude to God for sparing the family during World War II meant Mapa’s father made his own way in the world.

While Duran Duran and Imelda Marcos both briefly arrive in Mapa’s personal recollections, they’re largely populist pegs to hang the title on. More pages are occupied by a wide range of other trips into social culture, such as comments on the Filipino relationship with Catholicism, a surprising extension being a general tolerance. This memoir was produced before Roderigo Duterte’s antagonistic and repressive Presidential style, echoing the atrocities of the Marcos period she grew up in. While Imelda’s excessive spending and self-delusion is highlighted, the memoir’s longest section concerns the overthrow of husband Ferdinand, her parents first hand participants despite her Uncle being one of his ministers.

A couple of items are left hanging with no explanation, the most prominent a murdered Uncle seemingly not the government minister, but otherwise this is an immensely readable memoir. Mapa’s own enquiring personality shines through, as smart, cheerful, funny, and with a diverse range of interests. You want her opinion on Adam Lallana not working out at Liverpool and can only imagine how much she enjoyed the 2014 World Cup semi-final between Brazil and Germany. The most important aspect of any memoir aiming for more than sensationalism is a capacity for an emotionally honest view of the past, and while this isn’t confessional, Mapa has that honesty. Anyone reading Duran Duran, Imelda Marcos and Me will spend time with a raconteur, laugh and maybe even shed a tear before wondering where the time went. It’s great, and what a treasure for her family.