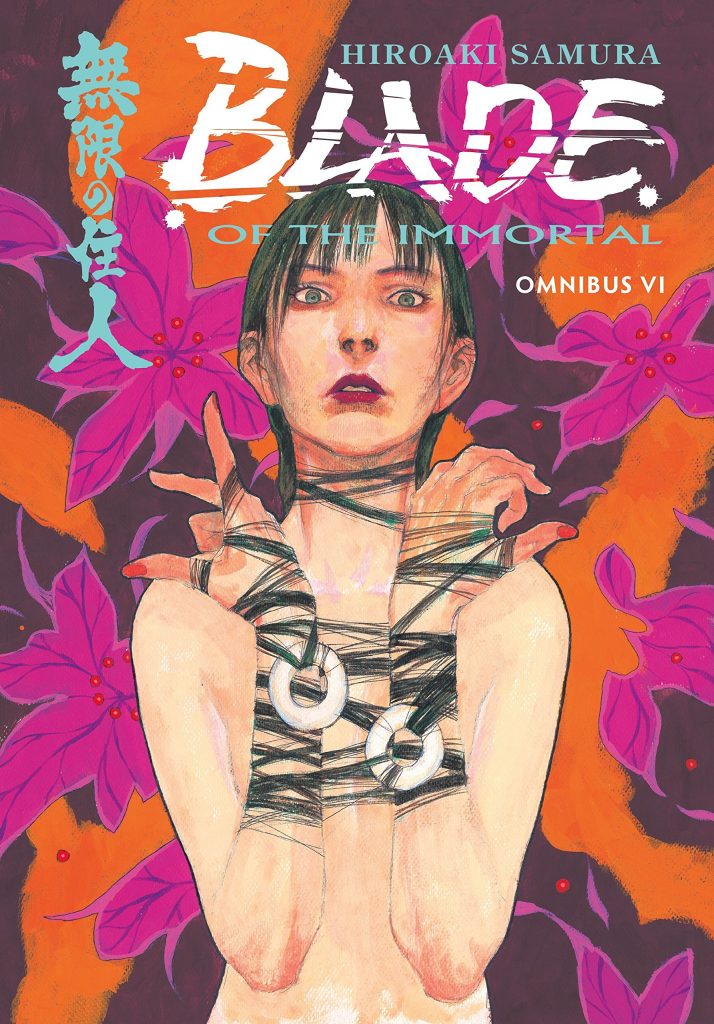

Review by Frank Plowright

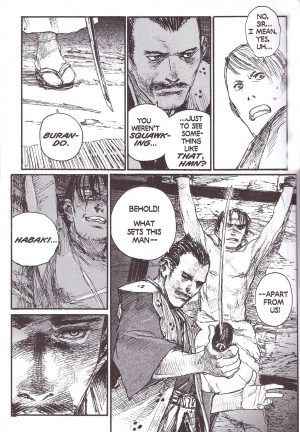

Manji is the immortal of the title, and that’s due to the worms placed in his body by a strange old woman in the opening volume. No matter how badly he’s injured, they somehow knit his flesh black together, even to the point of gradually generating a new limb. Readers may have been curious as to how that works, and so is local dignitary Habaki Kagimura, a complicated person, loving toward his own family, yet mercilessly capable of ordering atrocities. Having captured Manji he’s given doctors Mouzen and Burando a week to discover his secrets.

Hiroaki Samura has been astonishingly inventive to date, yet this chapter of Manji’s life raises the story quality further. Given an indulgent master and any number of criminals he can experiment on, there’s a distressing sadism to the way the doctors go about their business. Can they lop off one of Manji’s arms and graft it as a replacement to another person, thus transferring the healing capacity? In the pursuit of scientific knowledge they indulge in ever more sadistic practices, and it doesn’t make for comfortable reading. Samura is well aware of this, yet prolongs the dungeon experimentation throughout this combination of the slimmer paperbacks Shortcut, On the Perfection of Anatomy, The Sparrow Net and Badger Hole. It’s relentless over the first half, with few breaks away with other characters, and particularly graphic for emphasis over the first half of that, yet any accusation of sensationalism is deflected by the philosophical considerations Samura applies. A constant questioning accompanies the probing, and even chained to a wall Manji has his mouth, which is well used as a weapon, and contributes to a surprising disintegration. As the volume continues, Manji’s fate is presented as black comedy.

Away from Manji’s dungeon location, two women carry the remainder of the narrative. A considerable amount of space is given over to developing the already intriguing Dōa, a master swordswoman at sixteen, yet seeming much younger. Samura delves into her background and why she’s the way she is, eventually teaming her with Rin, who’s searching for Manji. In pretty well every other relationship as Blade of the Immortal runs its course, Rin is the youngster, looked down on by others, but Dōa accepts her almost as an elder sister. It’s essential, because when Rin and Dōa learn of people disappearing beneath the castle they begin to suspect where Manji is. Without Dōa’s almost supernatural skills Rin won’t progress far, yet her impulsiveness might equally be disastrous.

Under clumsy hands this storyline could be exploitative and gruesome, but Samura’s hands are more skilled than those of the surgeons in-story. No character intended to be around for more than a few pages is ever a voice without personality, and Dewanosuke is an example. His purpose is clear from his introduction, and he’s hardly without a stain on his conscience, yet Samura fleshes him out so skilfully that he’s someone whose inevitable fate we mourn. Toward the end there’s a rare rescue more convenient than usually plotted, but that’s the sole lapse in what’s been an astonishing volume.

This is an immense sequence. Blade of the Immortal has so many highpoints that ‘best’ is matter of personal choice, but the intensity, tension and multiple thought-provoking moments rank much of this as a contender. It tails off slightly by the end of the book, with Manji remaining in the dungeons, awaiting further experimentation in the seventh Omnibus, but perhaps Rin will come through.