Review by Frank Plowright

With the longest story running to five chapters, and only one other beyond two, Slay Per View offers considerable density from the sheer number of stories alone, whereas Murder 101’s title strip occupied half the book. It also supplies the largest number of artists contributing to a Sinister Dexter collection, thirteen in total, with series co-creator David Millgate, and previous mainstay Simon Davis restricted to a single chapter each.

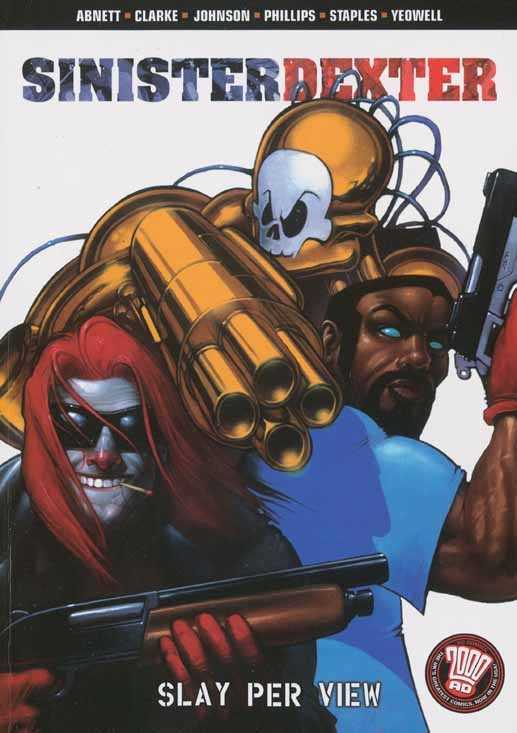

Dan Abnett and Greg Staples (sample art right) open the collection with a hilarious cockney police and gangster mash-up tipping the hat to assorted UK and US crime and cop films. Staples introduces the new short haired Sinister that would later become the standard look.

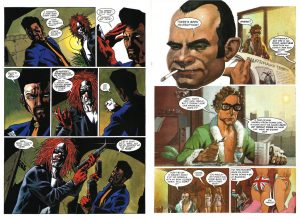

The two chapters of ‘To the Devil a Detour’ mark the first work of Andy Clarke (sample art left) who would go on to draw a lot of Sinister Dexter in Eurocrash and Money Shots, and because he’d become known for the precision of his line, it’s strange to see him erring toward cartooning on the opening page. It’s a neat story from Dan Abnett, who has Sinister and Dexter cursed. Sinister’s largely unconcerned to hear a gunshark called El Diablo is on their trail, while Dexter lets his imagination run wild. Clarke also draws the strangely touching ‘Bullfighting Days’ in which the young Sinister and Dexter first meet. Also strangely touching, and superbly drawn by Paul Johnson is ‘End of the Line’, a compact gem about a gunshark’s last day.

By these stories from 1998 we were long past there being any completely poor art on Sinister Dexter, so with a fair sprinkling of Clarke, Davis, Johnson, Staples, Steve Yeowell and one of only two strips Sean Phillips contributed, the drawing/painting is largely excellent. A couple of artists are ordinary, and a couple more, while already good, would improve. However, 1998 was also the era of primitive computer colouring, and some of the work in Slay Per View is vivid, to say the least.

Given the amount of stories here, it considerably trumps even the sheer variety of earlier collections, with Abnett casting his net far and wide for puns, pastiches and farce. Sinister becomes an acclaimed poet, we meet his wife, and he dies, while we’re introduced to Dexter’s girlfriend, and he becomes convinced he’s a serial killer in the title story (featuring Julian Gibson’s art). Perhaps funniest of all is how often Abnett manages to work references to Shakespeare and his work into strips about killers.

There are some weaker stories. Calum Alexander Watt’s only series art is good, but on the four chapters where Abnett stretches the master plan of a Bond style villain too far. A return for an innocent tax accountant re-runs his previous appearance (see Gunshark Vacation), and police contact Rocky Rhodes being kidnapped is Abnett going through the motions, accompanied by stiff figures from Steve Sampson.

Sinister Dexter collections don’t provide a complete run of the strip. As with the other collections, some strips produced around this time don’t make the cut, but what is supplied is solid, well drawn entertainment. Eurocrash is next.