Review by Graham Johnstone

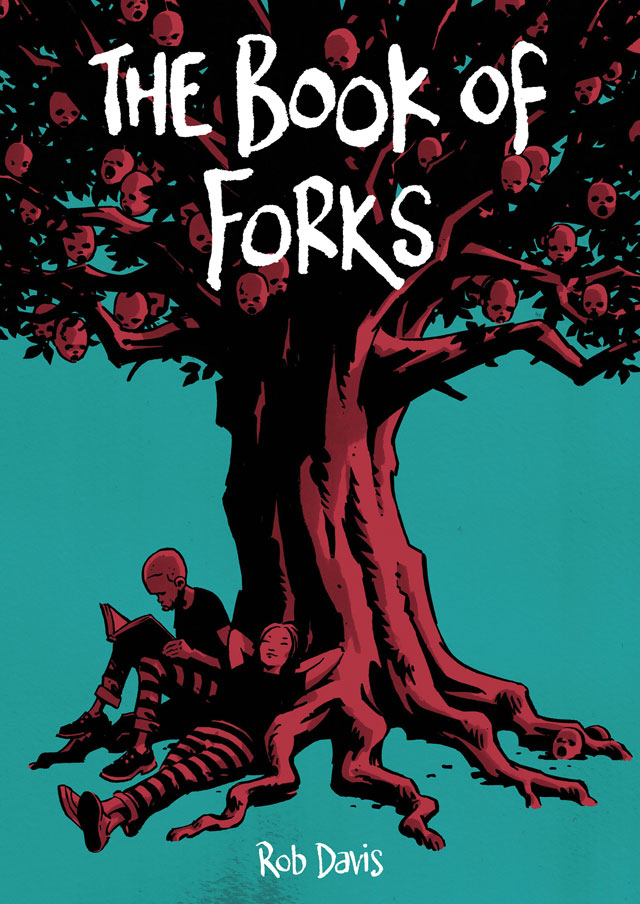

The distinctive cover colour and lettering reveals this as the third and final book in Rob Davis’ imaginative update on the school story that began with The Motherless Oven. School stories are a long-standing tradition in British fiction, and J.K. Rowling revived the genre with the addition of magical fantasy for Harry Potter. Davis further adds surreal whimsy and political satire.

Opener, The Motherless Oven began with the arrival of Vera Pike at the school attended by regular lad Scarper Lee, and introverted savant Castro Smith. School uniforms aside, this world is only tangentially like our own – here children construct their own mechanical mothers, live with talking appliance Kitchen Gods, and more centrally to the story, have predetermined Death Days. The approach of Scarper’s Death Day sends the trio on a quest for the oven of the title, seeking a way out of his supposedly inevitable fate, and the answers to some big questions.

Vera was very much the instigator – poking and prodding the others into this quest, and it was clear she had an agenda and a story to tell. The Can-Opener’s Daughter told that story – right up to her dramatic arrival at school – before picking up the quest from the end of book one.

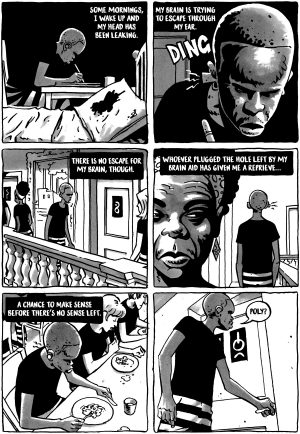

The Book of Forks, finally, focusses on Castro. He suffers from ‘Medicated Inference Syndrome’ and is compiling an encyclopaedic guide to their world – The Book of Forks itself. As this volume opens he finds himself in an institution called the Power Station, not knowing if he’s a patient, doctor, or a warder, and unable to communicate with anyone. At least until he meets a girl called Poly, with whom he experiences perhaps his first emotional connection. Vera and Scarper, meanwhile, have found a draft of Castro’s book and are trying to find him, to get the book finished and published, in the hope it will blow the lid off… something or everything. Their quest takes them through a series of imaginative realms and communities, each revealing a little more about the world, and picking up key threads from the earlier books.

The entries from Castro’s book are strategically placed in relation to developing events, and in themselves fascinating and witty. They certainly deliver on the cover-blurb’s promise to “explain everything”. Yet as the book progresses they outstay their welcome, and even as we reach the climactic last quarter of this final volume, they’re still throwing more concepts at us. It may have been better to have fed these through all three volumes, avoiding a backlog here.

The trilogy is Davis’ first major work as his own writer, and his ambition and originality are to be applauded. There are no familiar fantasy tropes here – and a discussion about who came before the ancients, who were before the immortals, gives a sense of the sheer scale of his conception. Ultimately, though, the intricacy of the story-world weighs down the story. However it does repay a second reading, skimming over some encyclopaedia entries.

Davis is an excellent illustrator and storyteller and renders the main characters and extended cast as distinctive and expressive, and he takes great joy in visualising the paraphernalia of the world. Aspects of the story don’t convince, though. As with the earlier volume, the eventual success of the quests seems over-reliant on coincidence, and the bonding between the pairs of young characters feels forced. On the other hand the final scene with Vera’s parents is as affecting as it is quirkily inventive.

It’s best not to start here, but if you’ve enjoyed the first two continue with confidence.