Review by Frank Plowright

He starts in the present day of the 21st century and a graphic designer with a problem, but Douglas Rushkoff rapidly moves back to World War II and a young American sent to the UK to consult with self-styled magic practitioner Aleister Crowley. Roberts is the innocent abroad, lacking personal belief, but swept away in the world of a man utterly convinced of magic and ritual, and its power to alter events on a grand scale.

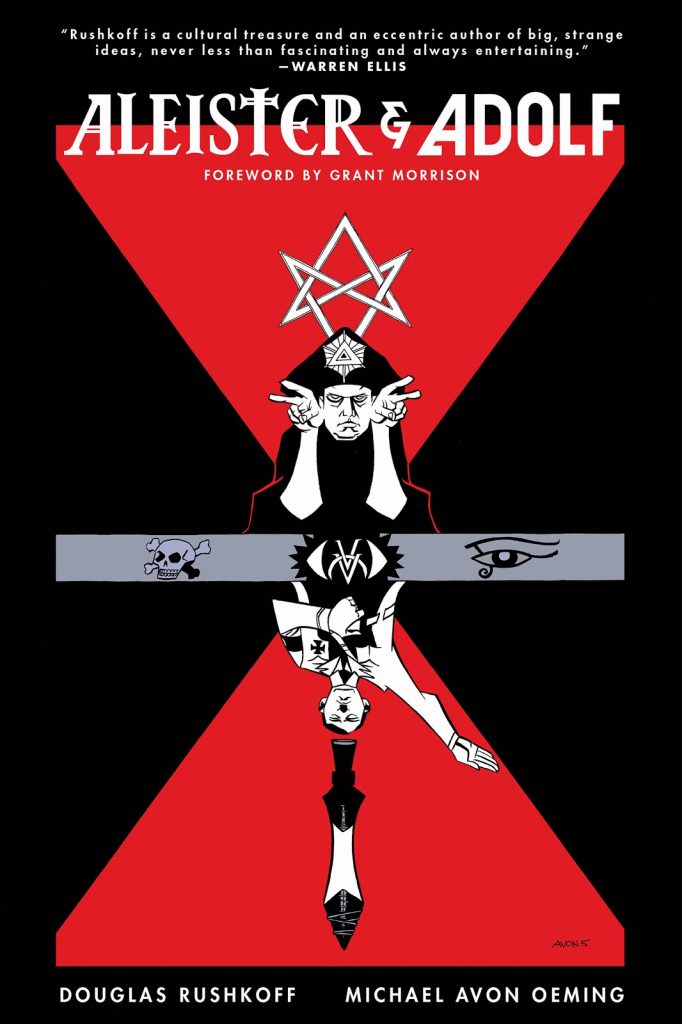

When both Warren Ellis and Grant Morrison provide glowing tributes to Rushkoff it’s an instant initiation for the media commentator and analyst into the world of comics. As with all his other works, Rushkoff brings a fiercely individual voice, and Aleister and Adolf can be read as a satirical extrapolation of his theories of media manipulation, dark arts being applied to images of mass communication. In an era when shorthand icons have impinged so deeply on the consciousness, who’s to say power doesn’t reside in symbols?

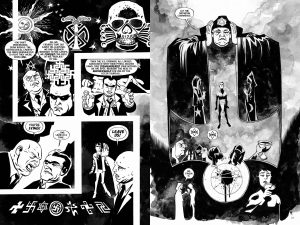

Already known for his shadowy black and white art, Michael Avon Oeming increases the contrasts to reflect the clash of innocence and darkness he’s drawing. The pages almost drip with black ink, the art perhaps more notable for being connected with an exploration of how imagery influences thought. Oeming delivers some remarkable images in different styles to reflect different circumstances. One that particularly embeds itself is a massive Crowley in full incantational regalia as gateway to the defence of the realm. His Crowley is distinctive, but Roberts can be confused with Ian Fleming, who’s a far larger presence than the cover billed Adolf Hitler.

A good story must convince the audience, and Rushkoff can’t transfer the skill of astute foresight from other ventures. There are sequences that captivate, but the mood is then dispelled via hokey pieces of nonsense such as Rudolf Hess proclaiming the swastika to be more powerful than pathetic sex rituals. Rushkoff covers himself by introducing voices doubting the clever string of tenuous connections earnestly presented as if meaningful, but that serves to distance further. The myth of the insulting V fingers sign originating with English longbow men during the Hundred Years War is connected with other V shapes, then linked with Churchill’s V for Victory exhortation. The biggest problem is that concentrating on symbols Rushkoff doesn’t establish real people. The cast do what they do to service the plot, and Roberts, never convinces as anything more than a wave-tossed twig, so fails as any source of audience sympathy. The framing structure of the present needing an investigation of the past is also awkward. In the light of later revelations an odd compulsion is eventually explained, but a more cohesive story would have dispensed with the opening in the present day and just segued there later.

Because Rushkoff is so influential and respected, there may be a tendency to suppress rising doubts about his lesser capabilities as a writer of fiction. However, anyone who can work their way past the ending should re-evaluate their critical faculties. Here Rushkoff all-but types his message in 48 point bold, attaches it to a mallet and visits every reader personally to hit them with it. For all the subtlety entwined in the thesis, it’s absent from the message.