Review by Frank Plowright

Maggie has been home educated, but now she’s the right age to begin attending Sandford high school, a rite of passage her three older brothers have already undertaken. She’s confused, uncertain and awkward, and her emotions are accentuated by her mother having recently left the family.

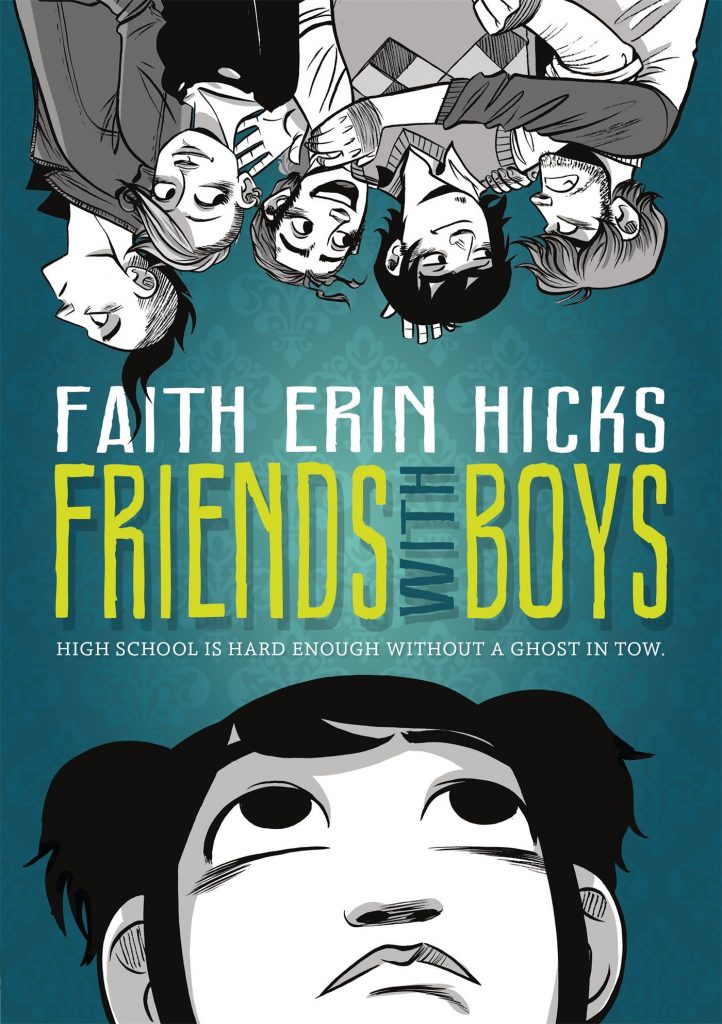

Faith Erin Hicks has always been an excellent storyteller with an emotional core to her work, but in places Friends With Boys is her most resonant work to date, focusing on a group of teenagers changing and reconsidering their recent past as they progress to adulthood. Maggie has a fine relationship with her Police Chief father and her brothers, but is nonetheless isolated, and finds it difficult to form other friendships even when people reach out. She also has the unique experience of being trailed by a silent ghost, by her dress someone from the 1800s, and only visible to Maggie, who’s known the ghost since childhood.

Hicks sets a leisurely pace, allowing for quiet and contemplative moments, beginning with Maggie observing her surroundings in the early stages, and thereafter providing pauses after dramatic moments. The relationships are strongly crafted. Maggie gets on with all her brothers, but can’t understand why twins Lloyd and Zander now fight all the time, while the oldest, Daniel, is a calming influence. There’s a further close bond between brother and sister Alastair and Lucy, who befriend Maggie, and much of the establishing work is down to the art, with Hicks extremely nuanced when it comes to providing a glance or an expression. These work well in combination with the rich surroundings emphasising moments of high drama.

At times points Hicks wants to make, such as comments on home schooling, are awkwardly inserted, and at others Friends With Boys tips over into melodrama, but those occasions are few in comparison with the wonderfully observed sensitivity. The plot heads toward a dramatic highpoint, but there may be some disappointment that there’s no great resolution to what’s been set up. Life goes on is the message, and that’s fine, but surely the rule of Chekhov’s Gun should have applied overall. Don’t let that put you off. There are enough heartbreaking and punch the air moments over the two hundred pages to make Friends With Boys a compelling read, and the art is wonderful.