Review by Ian Keogh

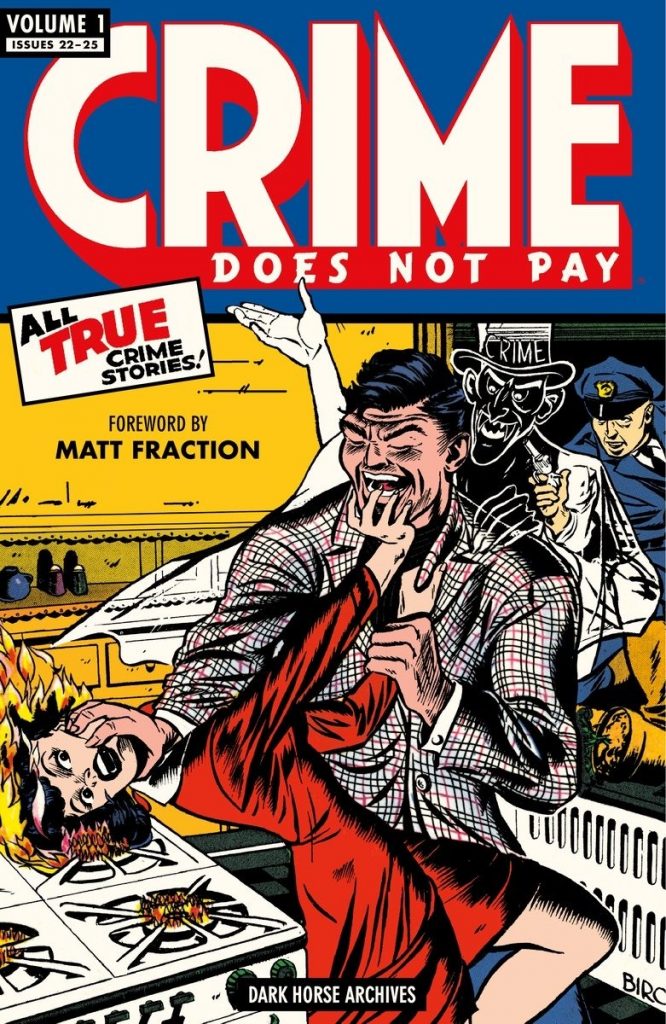

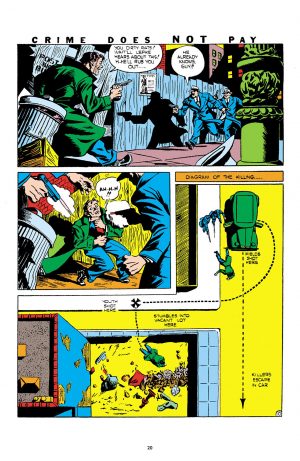

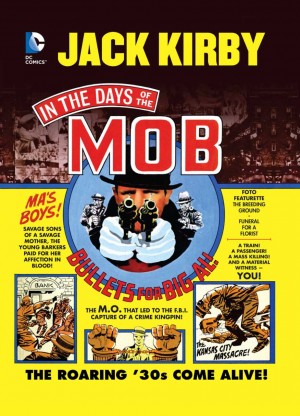

Has there ever been a comic as gloriously hypocritical as the 1940s Crime Does Not Pay? Solemn editorials despaired of crime, and the title ran across the top of every page, the world ‘not’ upped a point size, yet those pages revel in the thrill of violence as mobsters intimidate striking workmen, pour acid on rival furriers, and assassinate rivals. That’s just in Woody Hamilton’s opening biography of Louis Lepke, from which the detailed murder plan on the sample art originates.

The formula was simple, several pages of mayhem as a crook goes about their business ended by a single panel showing them brought to justice accompanied by sanctimoniously wordy text. While these opening issues aren’t as deliberately provocative as later content would be, there’s still enough to shock after all the decades. Dick Briefer is most likely to burst the boundaries of good taste, in one strip drawing two women dangled by their heels to drown in a well, and in another a crook smothering his mother with a burning pillow.

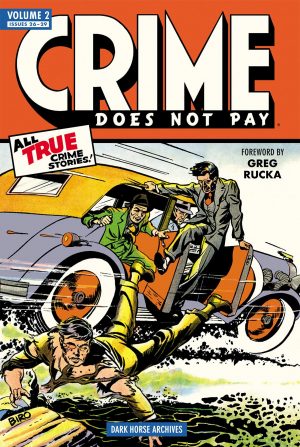

It’s an eye-opening revelation how many pages of lurid comics a dime bought in the 1940s, with this two hundred page collection only covering the first four issues of Crime Does Not Pay, each containing over seventy pages of strips. For all the claims of authenticity many of the stories are patently fabricated, but each issue opens with a brief biography of a 1930s gangster of relatively recent vintage on publication, Herman also producing John Dillinger’s exploits, with Dick Wood handling Legs Diamond and Dutch Schultz. While the comic would become the biggest selling of its era, there’s some introductory fumbling around as the series gradually settles into a formula. Bets are slightly hedged in the opening issue by introducing the flying superhero War Eagle, never seen again, the ghoulish Mr Crime introduces stories from the third issue, and Western crime strips feature throughout. Clue saturated, solve the crime strips are regulars, Norman Maurer astonishingly only sixteen at the time he began drawing for the title, already with a mature sense of storytelling and an elegance. Alan Mandel also impresses with a kinetic style owing much to Milton Caniff.

This material is still early days, a form of prototype for what would develop as higher standards prevailed, and while it has a lurid fascination it’s of greater interest as archival material than living, breathing, comics.