Review by Frank Plowright

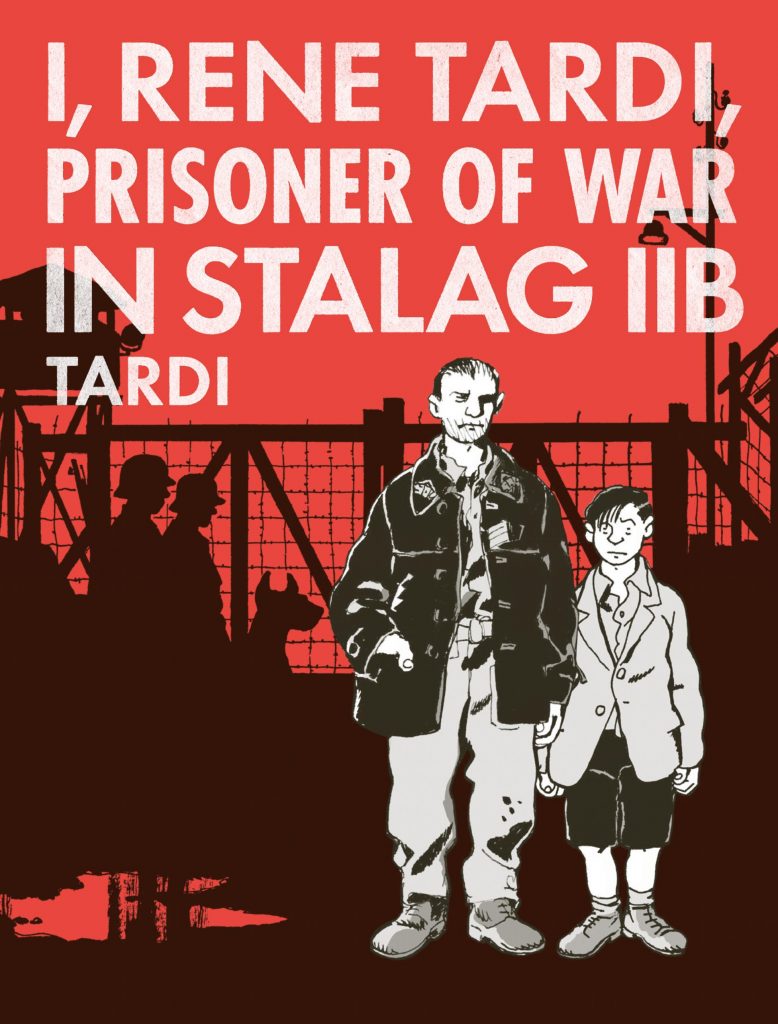

Like so many other Frenchmen of his generation, René Tardi was scarred by his World War II experiences, which amounted to a brief burst of combat followed by 56 months in a German prison camp. The consequences remained with him for the rest of his life, extending forty years past the end of the war. In 1980 Jacques Tardi asked his father to write down his memories of the prison camp. This exorcism filled three notebooks with writing and explanatory sketches, and almost forty years later Tardi, now his father’s age at death, has produced an extraordinary graphic novel from those recollections.

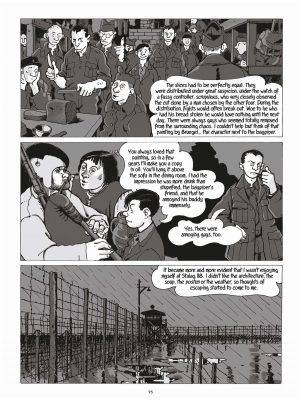

Tardi junior presents himself as a schoolboy extemporising around conversations about his father’s wartime experiences, conversations they no doubt once had, the younger Tardi with the benefit of hindsight all the while judging his father who volunteered for the army. The first third of the book takes the form of this questioning and response, first concerning family history, then René’s brief experiences in the tank corps before his capture. The remainder is the dehumanising life in the prisoner of war camp. Tardi’s compression of time is excellent. He extensively details the tedium where tiny variations count, and René’s brief period as a farm labourer. So much is packed in, the routine utterly dull without hope of escape, the constant hunger, and the absolute power the Germans had, yet two-thirds of the way through the page count it’s revealed what’s been read covers just the first seven months of René’s experience. He’d endure another four years. The younger Tardi continues to question, enquiring about inconsistencies in his father’s narrative, sometimes receiving an answer, sometimes noting questions he never asked, to which there is no answer.

It should come as no surprise that Tardi’s art is breathtaking. It’s in his now customary cinematic widescreen, three long horizontal panels to a page, and individual panels glorious visions. It’s some trick to simultaneously convey the squalor of the camps, the tedium of the existence and the random acts of cruelty breaking the routine so attractively. The passing of the seasons is acknowledged, but the greytones keep the scene consistently bleak and miserable while glassy eyed captives stare into the middle distance, Tardi never drawing pupils, just dots for eyes. Tellingly, the only colour is used on flags.

Some aspects of the recollections are heartbreaking. Modern day nutritionists consider potato skins to contain as many nutrients as the potato itself, yet men deliberately kept hungry ignored troughs of skins resulting from peeled potatoes. While hope evaporated in the camp after several years, Tardi includes reminders there was a life afterwards, referring to post-war events, and unusually for such recollections there are sympathetic Germans, also conscripted, but no keener on their country’s conquering policy than the French. Also interesting is how in the absence of some news it was eventually possible to assess how the German war effort was going simply by the replacement of the standard guards with very young or older servicemen.

This is only the first part of René Tardi’s reminiscences, taking him to 1945 and the camp evacuation, with The Return Home chronicling his eventual journey back to France. Distanced by decades, such first hand recollections have become rarer, now having a greater power than had Tardi started work in the 1980s, particularly as his own questioning presence echoes the even more harrowing memories of Maus. It’s not as consistently distressing as Maus, but I, René Tardi is a touching and humane read, more compellingly drawn. Too many comic creators have a golden period and then tail off. That’s not Tardi.