Review by Karl Verhoven

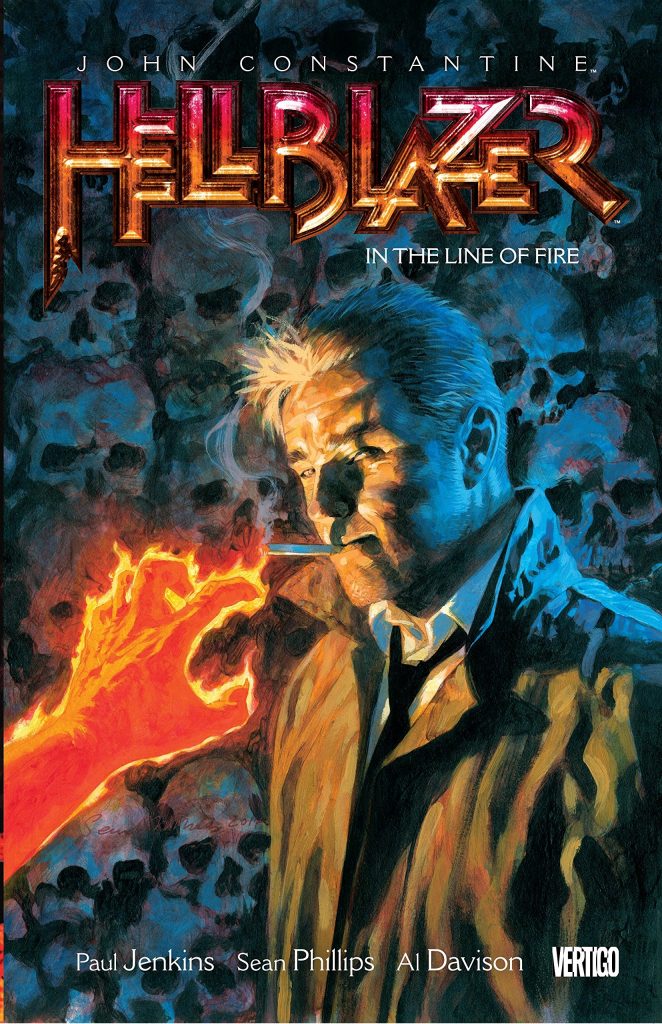

In order to solve what seemed to be an inescapable trap, John Constantine pulled off a last minute reprieve in Critical Mass by sacrificing the demon blood he carried within him. In the Line of Fire begins with the unforeseen consequences, not least a considerable diminishing of Constantine’s tolerance for alcohol. That’s why he’s out in the woods at three in the morning for an effectively touching opening story, featuring a great ending that Paul Jenkins has been waving in our faces throughout.

Jenkins is good at capturing Constantine’s sardonic tone in narrative captions, and like picking at scabs he picks at Constantine’s past, unearthing what’s best left untouched. He’s also good at the deception and manipulation of Constantine’s world, ensuring it’s only rarely that the truth is plain and obvious. And that it usually comes with a punch to the gut. That’s reiterated several times over the succession of individual stories comprising the first half of this collection of mid-1990s work.

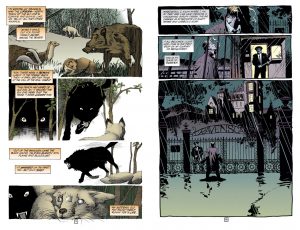

It’s almost all illustrated by the supremely adaptable Sean Phillips. Most of the book is in his recognisably efficient style, but he’s capable of surprising, and frequently. Among visual versatility are some pages of faux classical Japanese art, some scratchy charcoal nightmares, and several pages of animal illustrations that wouldn’t be out of place in a children’s book. Phillips is now recognised as a craftsman, but this is from is under-rated period, yet he’s so good it seems inconceivable that he could ever have been under-rated. He’s spotted for one episode by Al Davison, also good, but with occasionally stiff figures and not helped by working on the collection’s weakest story.

For the longest sequence, the three chapters of ‘Difficult Beginnings’, Jenkins comes up with a good metaphor for Constantine’s revised personality, that of the one sided coin, and it reinforces Jenkins’ talent for encapsulating types. “Daddy stands firm with the eyes of Britain upon him. The stupid, burly bastard and his working class bravado” or “Trevor Pritchard lives the best of lives. He’s always in control”. Throughout In the Line of Fire Jenkins offers multiple pithy and impressive character summaries of that nature. The title story is almost heartbreaking, the most successful emotional dramas being those without Constantine at their centre as he pretty well deserves everything that comes his way. Over two parts, the first seems rather ordinary, but it sets up a conclusion that ought to bring a tear to your eye.

In the twenty years between publication as comics and this collection times have changed, and some aspects now stand out further. Jenkins isn’t condoning the homophobic lyrics sung by English football fans in one story, but they’re printed, when today it’s more likely they wouldn’t be. Strangely, it’s found in the weakest story in this collection, possibly the most personal for Jenkins, but a trivial contrast to the way he otherwise gets under Constantine’s skin with details too obscure for many. Irritatingly, for the football literate, several of those details are screwed up by others, a white red card, and stadium names mis-spelled.

This collection of John Constantine tales has heart and tarnished soul to match better remembered and more highly regarded Hellblazer material, and shouldn’t really have waited eighteen years before being issued as a trade collection. Last Man Standing is next.