Review by Frank Plowright

A combined five volumes of lushly drawn fantasy begin when intrepid and eccentric explorer Andrea, and his more fearful assistant Elwood crash their plane on a river island occupied by two distinct species. They’re humanoid and intelligent, but while the Limpids are basically human, if able to become invisible in darkness, the other is a form of rodent known as Ferrets. Both races consider themselves exiles, and rub along uneasily, with considerable animosity and resentment. The newcomers more resemble the Ferrets, but view themselves separately, and it’s discovered both races have a purpose that ties into the continued safety of a world. It’s the Limpids who prove the friendlier, with Orane and her Uncle Theo helping with an escape.

This Angoulême award winning fantasy is dense, layered, and unfolds in puzzling snippets providing some aspects of the bigger picture, but usually raising further questions. For the less patient reader, the back cover blurb provides the background that’s eventually revealed in full at the start of the fourth episode, having been trailed in the first.

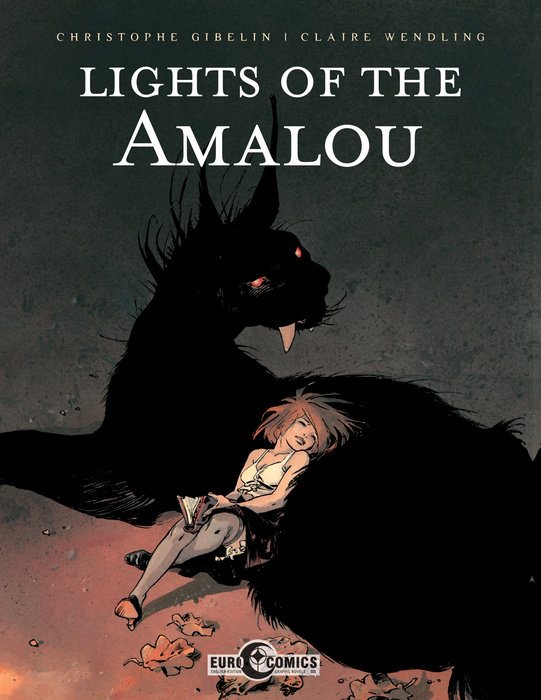

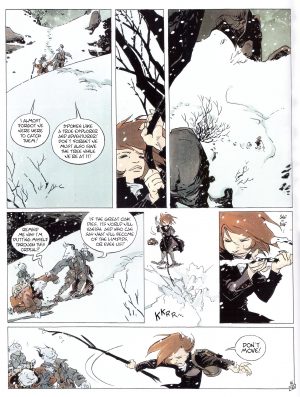

Claire Wendling is better known as an illustrator and designer, restricting her comic art to Lights of the Amalou, but having studied at the home of French comics in Angoulême she’s confident with sequential storytelling. Her loose, illustrative style, reminiscent of American artist Arthur Suydam during the 1980s, is detail packed and there’s no fear of using space, both as a storytelling device and to accentuate size. Individually the designs for a succession of creatures are imposing, but they’re mismatched, never presenting a cohesive visual identity.

At the heart of Christophe Giberlin’s plot is a very delicate balance between representations of two opposing and overwhelming powers, with certain creatures able to affect that balance. The Ferrets are devious and conniving, and their lack of scruples is easily manipulated to set off a chain of events that one character hopes to benefit from. Orane and Elwood eventually slot into lead roles, both of them having grown from the timid personalities introduced in the opening chapter. It’s a template and progression very much influenced by Lord of the Rings.

The Lights of the Amalou is a strange tale that takes too long to smoulder into life. It’s rich in fantastic ideas, beautifully drawn, deals with universal themes and the existence of everything is at stake. When balanced against that the flaws appear minor and inconsequential. Wendling’s style often makes it difficult to identify who’s at the heart of some scenes. Foes built up as immensely dangerous are all too easily restrained. In hindsight almost all the lighthearted opening episode reads as if it’s a different tale with different priorities. The biggest problem is the peculiar starting point of someone eventually revealed as a major villain, which makes little sense as they have the resources to change the situation we first meet them in. Enough interesting scenes occur beforehand to capture the attention, but it’s only the final two chapters that finally get to grips with an epic quest, and they thrill as they twist about, although as noted, some threats are too easily quelled.

The result is to restrict unvarnished admiration for The Lights of the Amalou to anyone who really loves their Tokienesque fantasy. For anyone else, the holes are too apparent.