Review by Frank Plowright

Anyone wanting to produce a confessional autobiographical piece, if exaggerated for satirical purposes, could surely make no better opening statement of intent than a full page of the author sitting naked on the pot. It indicates nothing is concealed, and if that comes across as unnecessarily crude, you’re not going to want to venture further. Airboy is one debauched, post-modern, semi-autobiographical graphic novel.

James Robinson’s greatest acclaim has come from work on superheroes, most effectively supplying a reverential modern view of characters whose origins lie long in the past. Image Comics believe he’s the man to relaunch Airboy, a World War II character for whom he has no affinity and for whom he struggles to find an approach. This is all established in the opening autobiographical section, where the fictional Robinson’s solution is to bring artist Greg Hinkle to San Francisco in the hope that batting ideas back and forth will provide a viable Airboy story. Let’s just say, it doesn’t go to plan.

Part of that is because after a pretty intense night of substance abuse and casual sex, Airboy manifests in the motel room, and from that point Robinson’s story becomes one of contrasting the attitudes of the early 21st century with those of the 1940s. A condescending attitude to the simple morals of 1940s prevails today, and at the point where it looks as if Robinson’s lost the plot he pulls it back again by ensuring there’s a reciprocal immersion for the present day writer and artist, ensuring they’re faced with ethical dilemmas of that era.

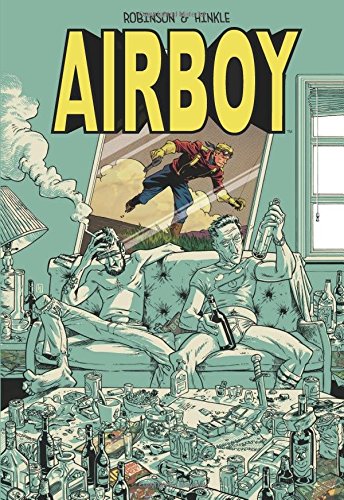

Hinkle’s art is superb throughout. His sketchy cartooning is ideal for the 21st century and the detail he provides is appropriate for both filthy motel rooms and Nazi war machines. The most immediate impression concerns his colour choices. As per the cover, he opts to present the 21st century in dull shades of green and the 1940s in full colour, and characters from those eras retain those aspects when elsewhere. Reversing the usual visual trick could be seen as a commentary.

When serialised, controversy was generated by Airboy’s aggressively repugnant attitude toward transgender people. Yes, it’s offensive, but Airboy is supposed to be someone from the 1940s with the attitudes prevalent at the time, and that scene fits the narrative tone, establishing Airboy as a man out of time, and is balanced by an opposing view.

Airboy is self-indulgent on Robinson’s part, and among his harsh self-flagellating, self-portrait is the admission he’s unable to cope with his circumstances, which results in his working out his problems on the printed page. This, however, is anchored by a viable plot with other concerns. It’s occasionally provocative for provocation’s sake, and may or may not have provided the catharsis Robinson required, but it’s fascinating and frequently hilarious. It’s also completely unlike any other graphic novel where the creators place themselves at the centre of an adventure story (not that it’s an overflowing genre). Robinson’s afterword notes that he considers Airboy among the best things he’s ever done. He’s right about that. Those who want every nut and bolt explained may be disappointed, but as transportation between eras is merely a means to a far greater end, is it worth slowing the story down to contemplate the irrelevant mechanics?

One other thing worth noting is that the hardcover edition is without dust jacket, so resembling the British comic annuals of Robinson’s childhood. It’s a viable and attractive format, so why isn’t it more frequently used?