Review by Ian Keogh

The ambition of David Lapham’s storytelling is on display over the eight chapters presented in Other People. The realistic dialogue and well-plotted drama are now familiar, so Lapham returns to toying with time. There’s at least one story set in every year from 1982 to 1986, but not in chronological order. He’s also integrating the previously isolated Amy Racecar material, fantasies constructed by the thirteen year old Ginny, whose narratives intrude on the real life of the opening chapter.

His uniting theme is infidelity, the risks, the costs and the complacency, but the constant switching between years evolves a satisfying puzzle. In the opening episode we meet Janet, mother to Bobby who’ll feature again in the series. She’s very much the libertine, at home with her sexuality and exploiting it for pleasure. A year earlier, as seen in the second story, she was a very different woman, not loyal and chaste, but hardly the sybarite seen earlier. Later in the book we have another episode from 1984 featuring Janet, and it seems as if Lapham has confused his dates, but he’s having a laugh at the alert reader’s expense. The tone of the assorted stories switches from the broad farce of the opening chapter to regular character Beth’s frightening abuse of power in the closer. One character is empowered by surviving a terrifying experience, another desperate for the unattainable and prepared to wreck a marriage. Oddly, few of those portrayed by Lapham end up as contented individuals.

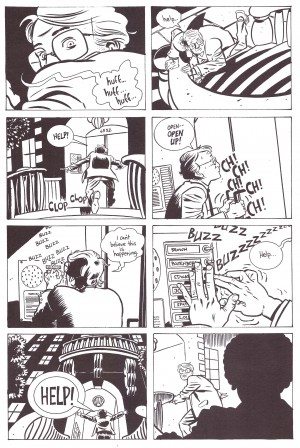

The most complex and disturbing of them is Amelia, She derives power from her ability to lure men away from their wives or girlfriends, and they easily fall hard for her, yet she’s manipulative and ultimately self-destructive as control becomes her guiding force. Lapham draws her escapades in a manner resembling the layouts of Jaime Hernandez, employing a greater clarity, and artistic experimentation is key throughout Other People. The most surprising to see is a version of the style employed on 1950s crime comics, heavy on the inking and with tight, claustrophobic viewpoints. Johnny Craig may be the influence here. As previously, Lapham toys with mutating his style to resemble others, but the foundation is all his own work. In the notes accompanying the 2001 hardcover edition, the better buy if it’s available at a reasonable price, Lapham relates how he’d reached a point where he wanted to tell some stories that couldn’t be accommodated in the Stray Bullets format, and had come to resent the demands of a regular series slightly. Perhaps the artistic changes were a way of keeping him interested.

Again, the crime genre so associated with Stray Bullets is actually relatively minimally applied to this collection. Monster, an increasingly interesting character, makes an appearance, and there’s one rabid revenge fantasy, but for the most part the tension and suspense is dramatic and emotionally based. The Amy Racecar interlude is one of Lapham’s best. This time she’s a private detective with an increasingly complex trail of deceit to follow, and Lapham again cleverly employs the experiences of Ginny Applejack into the farce.

The genre may have shifted, but this is another compelling collection of first rate stories. Dark Days follows, and both can also be found within the series encompassing Uber Alles Edition.