Review by Frank Plowright

As an Underground artist prominent since the late 1960s, Manuel ‘Spain’ Rodriguez came far later to memoir as inspiration for his work than many of his contemporaries, only really exploring the form from the 1980s. He’s very good with it. All too many comic creators dispensing autobiography haven’t really lived enough to accumulate engrossing material. Rodriguez is brimful of stories, and because these are anecdotes from a life lived they’re gripping and suspenseful.

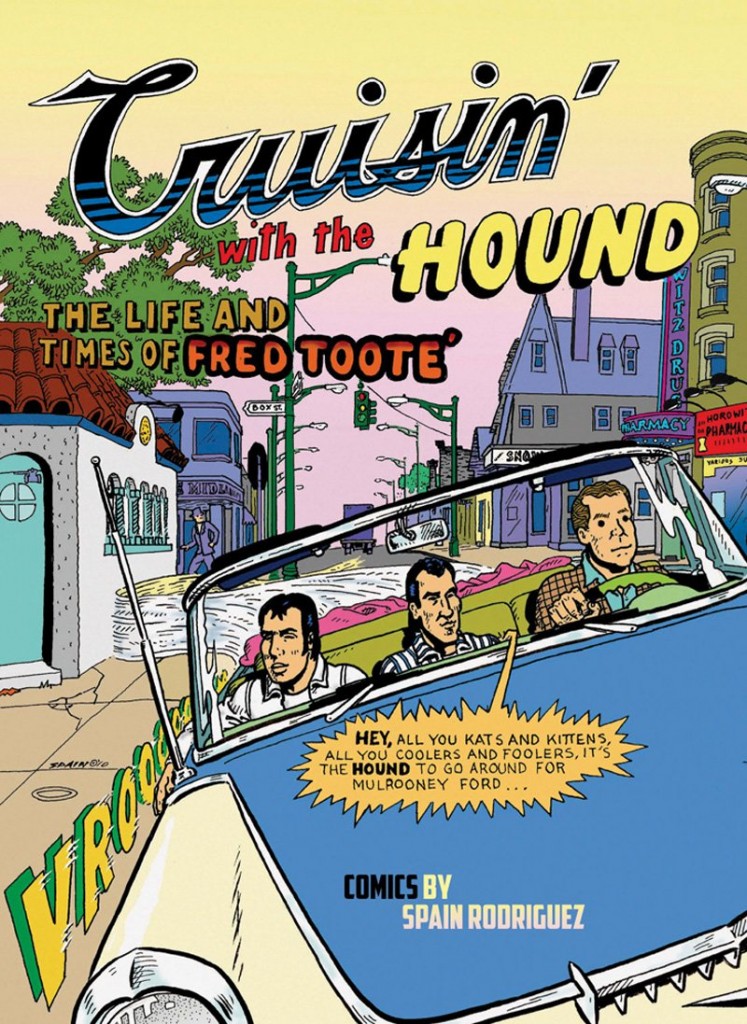

Rodriguez’s art is more of an acquired taste. It’s stiff and exaggerated, but detailed cartooning where people don’t always look quite right, and because the work anthologised in Cruisin’ With the Hound was produced over a fifteen year period there’s a variance within that style. Some strips have an almost dashed off looseness to them while others are far tighter. Technical perfection, however, wouldn’t be as effective, since the most important aspect of the art is that it drips with sordid atmosphere as Rodriguez brings the seedier side of the late 1950s to life. The detail is astoundingly well recalled, with locations, vehicles and clothing all wistfully portrayed.

Fred Toote was the most eccentric of several characters Rodriguez recalls from his disaffected youth, during which rebellious delinquency was his escape from stifling religious conformity. The way he’s portrayed, Toote was an intellectual eccentric whose company was never dull. He was surrounded by youngsters who resorted to their fists more often than not, yet Rodriguez depicts him as someone always able to think and joke his way out of trouble. Others from the neighbourhood weren’t as fortunate, and there’s a non-judgemental understanding of circumstance in the way Rodriguez portrays them. The Hound of the title was a Buffalo DJ whose radio shows provided the soundtrack to a night’s activities.

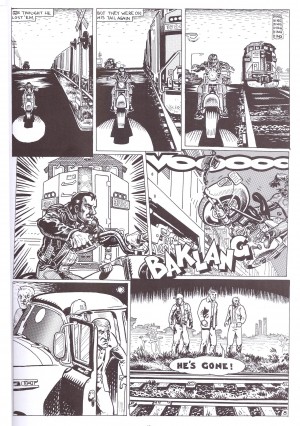

Rodriguez later allied himself with bike gang the Road Vultures, and stories about them were his first steps into autobiographical material. The ones featured here are more aggressive and violent than the remaining strips, but this isn’t glorification as the consequences of violence are vividly shown. While equally good, they provide a jarring contrast to the lighter tone of the remaining strips, and might have been better separated rather than sifted among them. Another minor quibble is the lack of closure. What happened to Toote? Did he survive the era? Does he run a Dow Jones company? Does he write under the alias ‘Michael Chabon’?

As the material about Toote and the Road Vultures occupy most of the book, the remaining content can be considered worthwhile bonus material. 35 pages excerpt editor Gary Groth’s 1998 interview with Rodriguez, and are accompanied by smaller reproductions of further strips where the autobiographical selections move beyond the 1950s. The insight provided by Rodriguez’s interview comments contextualise the earlier strips, providing the causes of frustration, then rebellion.

Rodriguez is never mentioned among the first rank of autobiographical cartoonists, and that’s surprising. Perhaps his lumpy art puts people off, or they’d prefer to read about tamer topics, but there’s a rare visceral honesty to Rodriguez’s work. Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb match it, and Joe Matt at his most repulsive, but all too often there’s the feeling of autobiographical restraint elsewhere. Not with Rodriguez. It’s time more people knew that.