Review by François Peneaud

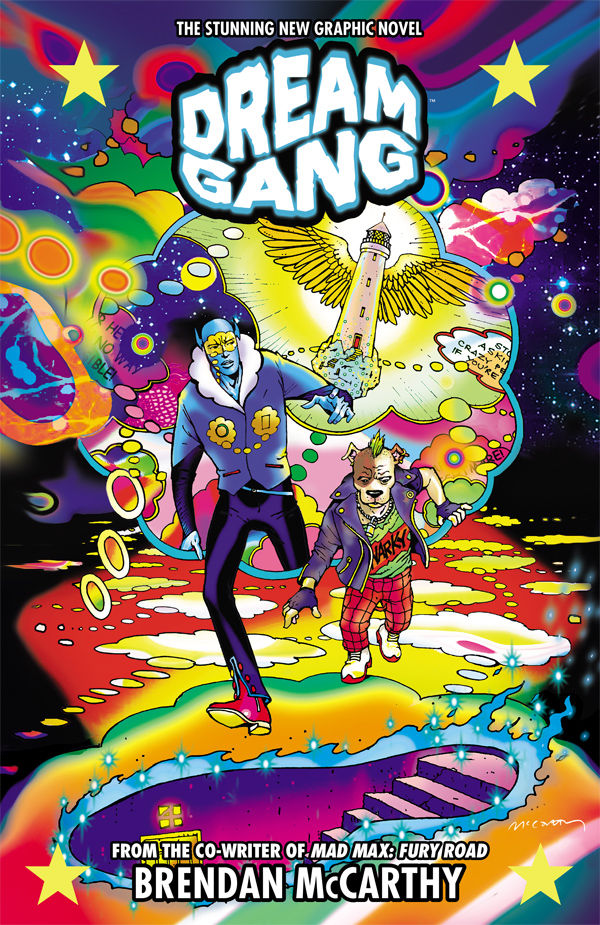

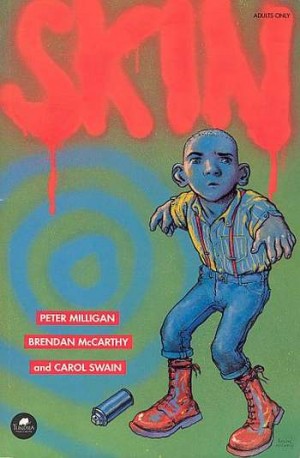

Brendan McCarthy’s art has always had a dream-like quality, especially in its wilder flights of fancy. The artist, better known for his collaborations with writer Peter Milligan and his work on the Mad Max: Fury Road film, now goes full throttle with that aspect of his art, offering the tale of a young man who faces a very weird threat right in the middle of one of his dreams.

Patrick lives in a dull, grey world. His dreams, however, are in Technicolor and full of adventure, even of danger. He dreams of himself as a child, lost in a topsy-turvy world where a pointy creature assaults him. Saved by a sheriff from the Thought Corps, he’s given an avatar to protect him, a Dream Voyager. He soon learns that the dream world is endangered by Zeirio, a construct with desires of his own. Desires of destruction. Allies and enemies appear on every page, building up to a reality-shattering crisis.

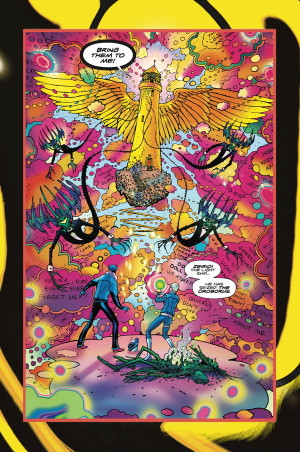

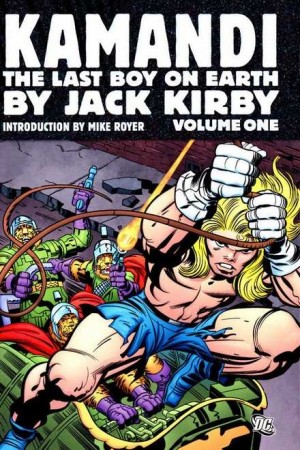

McCarthy’s dreams on paper are certainly unlike anything in comics (the closest things would be something out of Grant Morrison’s run on Doom Patrol): a winged lighthouse prowling the dreamfields, geysers of premonitions which can send you into somebody else’s future, a villain with a headgear that puts Jack Kirby’s many-angled inventions to shame (Kirby being an obvious influence on McCarthy), nightmare entities with burning planes sitting on their cowled heads… McCarthy also shows a mastery of colouring that makes his work instantly recognisable. He’s probably more thought of as a bright, wild colours guy, but it would be more correct to say that he’s a master of colours as mood enhancers: case in point, his use of a greyscale for the “real” world as opposed to the full spectrum for the dream world. Readers might be forgiven to think that he’s using a cliché; it is in fact integral to the story and to Patrick’s personal journey, as he comes to terms with his reunion with a long-lost childhood friend.

There are other neat visual tricks, such as the swirling borders surrounding the pages and plunging the reading itself into a deeper, turbulent world. Numerous thought balloons in the background are never linked to one particular character and act as a piece of the puzzling environment that Patrick discovers.

There’s a strong allegorical side to some of McCarthy’s creatures and situations, which is not surprising for a story set in dreams. The most striking might be the Forgetting Vortex, where dreams disappear from memory as they fall in it — it’s rather funny to think of the similarities between the Vortex and the Memory Dump from Inside Out, the Pixar animated film. As in the film, the Vortex can be seen as both a danger (for the dreams themselves) and a blessing (for the dreamer, who needs to forget some things). McCarthy’s comics might be pretty on the surface, but they are also anything but empty of meaning.

In fact, McCarthy skilfully blends the large scale adventure of the dream denizens with the more intimate odyssey of the main character. Some of McCarthy’s stories are more about the meandering than the endings and somewhat lack focus — though, of course, the journey itself can be the point. This time, thanks in part to the various levels of the story, there’s a journey and a goal. Dream Gang is certainly a good introduction to McCarthy’s brand of storytelling; for readers already familiar with his work, the pleasure of a full story done on the artist’s terms is noteworthy.