Review by Frank Plowright

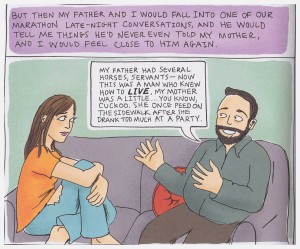

Magazine feature writer Laurie Sandell grew up in a household barely able to contain her father’s larger than life character. Fearsomely intelligent and compulsively secretive, her father’s tales of his past captivated the young Laurie who basked in the special relationship shared with him as the oldest of three daughters.

An Argentinian born to German parents, he arrived in the USA in time to fight in Vietnam, before building a career as a university lecturer, but apparently with numerous sidelines. When Laurie attends college an impulse to buy a pair of shoes leads to the metaphorical tug on the rug beneath her assumptions. Discovering one of her father’s secrets unravels others, and the benign acceptance of her family frustrates and confuses. Ironically it’s the very capacity to absorb herself in the fantastic that provides the skills required to become a successful celebrity interviewer, but as her star rises, her personal life falls to pieces.

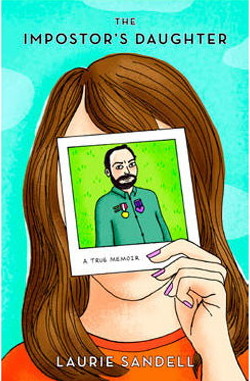

The Imposter’s Daughter has two narrative strands, one focuses on the man Sandell refers to by the distancing term “my father”, and it’s coupled with his affects on the adult Laurie. It recalls Fun Home and Maus, both acknowledged by Sandell in her bibliography, and both investigating fractured parental relationships, but both produced by more adroit writer/artists. Maus‘ twin narratives grasp the reader, but Sandell’s extensively detailed relationship difficulties and celebrity worship aren’t unique enough to strike any chord, resulting in a significantly sagging mid-section. Worse still, much of the celebrity-related content is superfluous, so comes over as gratuitous name-dropping. The problem becomes, as the Laurie of the narrative in effect acknowledges, that her father’s lies are far more compelling than her truth.

For the most part it would be desirable for the writer of an autobiographical graphic novel to draw the book themselves. However, Sandell’s artistic talents fall well below her writing competence, to the point where those picking the book up and flicking through may be put off. Even acknowledging the child-like art reflects the inner Laurie Sandell, a very basic flat style is far from visually compelling, and inadequately conveys the emotional subtleties. There are jaw-dropping and page-turning sequences to The Imposter’s Daughter, but they’re dragged down by the remainder.